Cyber-Goggles: When China’s Tool Box Looks Like a Pile of Cyber-Hammers

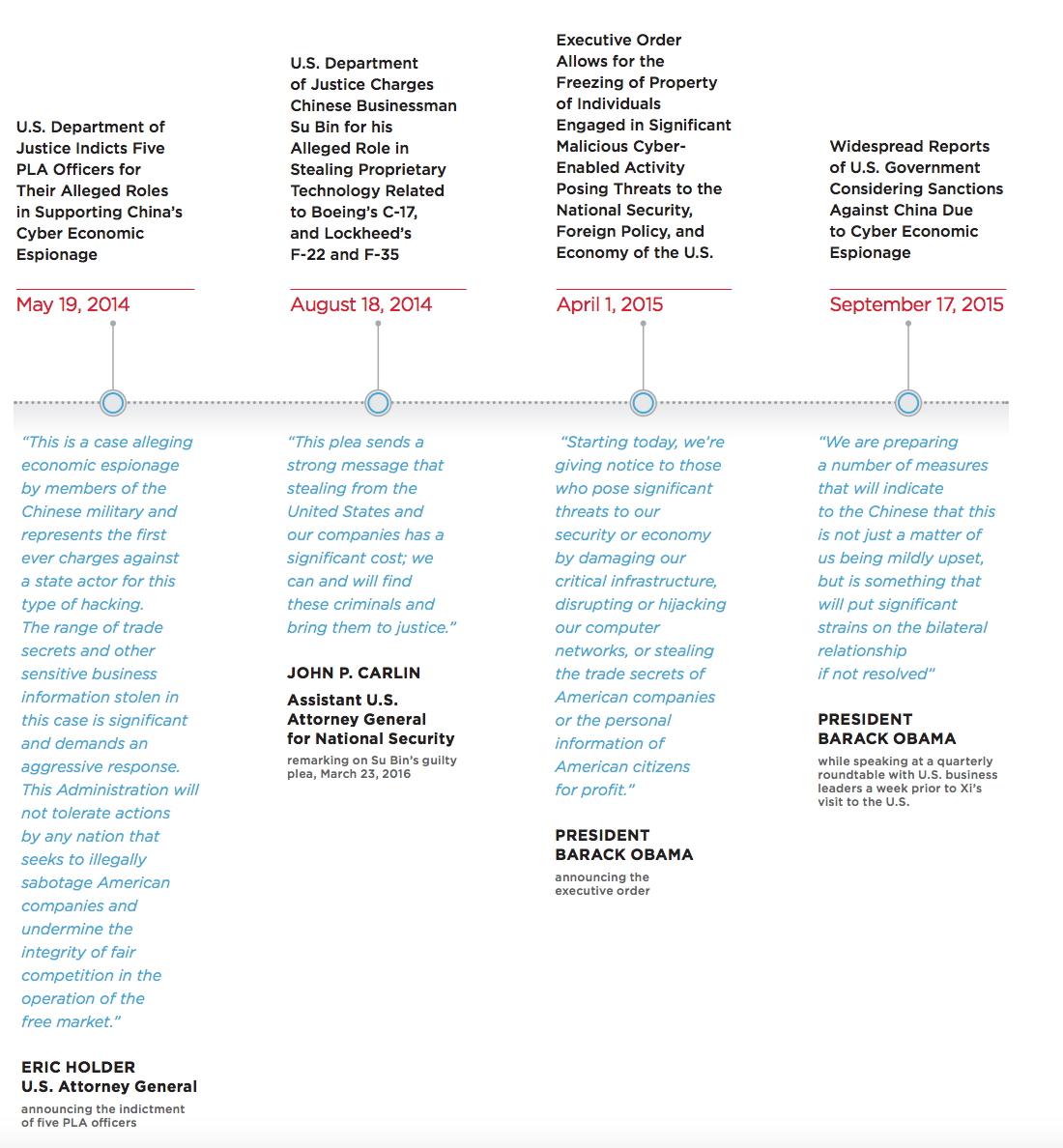

Last week, the cybersecurity firm FireEye released a report largely declaring victory over Chinese cyberspying. The report itself is suspect. It spends two pages talking about internal issues — such as Xi Jinpeng’s efforts to consolidate power in China — then throws in a timeline designed to suggest actions the US has done has led to a decline in spying.

The timeline itself is problematic as it suggests both indictments — of some People’s Liberation Army hackers targeting industrial companies and one union, and of Chinese businessman Su Bin — as IP hacks.

In May 2014, the U.S. Department of Justice indicted five PLA officers, marking the first time that the U.S. Government has charged foreign government personnel with crimes related to commercial cyber espionage. Although China warned that the move “jeopardizes China U.S. cooperation,” the Department of Justice indicted another Chinese national, Su Bin, the following August for allegedly orchestrating a cyber-enabled economic espionage operation targeting U.S. defense companies.

Neither should be classified so easily (though the press has irresponsibly done so, especially with respect to the PLA indictment). As I have laid out, with one exception the PLA indictment treated the theft of information pertaining to ongoing trade negotiations — something the US engages in aggressively — with the exception being the theft of trade information that China might have gotten anyone as part of a long-standing nuclear technology transfer deal with the target, Westinghouse. And while Su personally profited off his spying (or that’s what he said as part of pleading guilty), the targeted items all have a military purpose.

Without any internal evidence to back the case, FireEye declares that these indictments (the former of which, at least, relies on intelligence shared by FireEye division Mandiant) had an effect in China.

In 2014, the U.S. Government began taking punitive measures against China, from indicting members of the PLA to raising the possibility of sanctions. These unprecedented measures, though met with skepticism in the U.S., have probably been taken much more seriously in Beijing.

[snip]

In 2013, when we released the APT1 report exposing a PLA cyber espionage operation, it seemed like a quixotic effort to impede a persistent, well-resourced military operation targeting global corporations. Three years later, we see a threat that is less voluminous but more focused, calculated, and still successful in compromising corporate networks. Rather than viewing the Xi-Obama agreement as a watershed moment, we conclude that the agreement was one point amongst dramatic changes that had been taking place for years. We attribute the changes we have observed among China-based groups to factors including President Xi’s military and political initiatives, the widespread exposure of Chinese cyber operations, and mounting pressure from the U.S. Government.

The report then shows an impressive decline of perceived attacks. But even there, there’s no granularity given about where FireEye is seeing the decline (or whether these numbers might rise as it response to attacks on companies that will call FireEye in for hacks that started months or years ago). Again, in its description of the ongoing attacks, FireEye includes a lot of things that every country but the US would consider to be clear national defense hacks.

In the wake of the report, there has been some even more overheated victory laps about the success of the US-Chinese agreement in 2015, as well as this utterly absurd piece insisting that the US doesn’t engage in economic espionage. The piece is particularly nonsensical for how it uses evidence from Snowden.

More importantly, the U.S. does not steal information to give to its companies, as a rule. That none of the documents released from the vast trove of material pilfered by Edward Snowden points to this kind of commercial espionage is indicative. Those who control the Snowden documents are eager to release anything that would harm the U.S., yet they have not yet produced an example of information being given to a U.S. company.

[snip]

What we know of American espionage against foreign companies (thanks to Snowden) is that the intent of the espionage against commercial targets is to support other American policies: non-proliferation, sanctions compliance, trade negotiations, foreign corrupt practices, and perhaps to gain insight into foreign military technologies. The U.S. as well as other nations who care about such things regard these as legitimate targets for spying—legitimate in the sense that this kind of espionage would be consistent with international law and practice. This spying supports foreign policy goals shared by many countries, in theory if not always in practice.

I say that because there’s no evidence from most domestic companies that NSA interacts with — not the Defense contractor targeted in a cyber powerpoint, and certainly not any of the telecoms that partner with the government. You would, by definition, not see evidence of what you’re claiming. Moreover, ultimately, this is retreat back to a fetish, the description of certain things to be a national good (like the trade negotiations we’ve indicted China for), but not others.

Ultimately, American commentators on cybersecurity continue to misunderstand the degree to which our corporations — especially out federal partners — cannot and are not in practice separated from a vision of national good. Though discussions about the degree to which tech companies should be wiling to risk overseas customers to spy without bound is one area where that’s assumed, even to the detriment of the tech company bottom lines.

Here’s what all this misses. There is spying of the old sort: spying on official government figures. And then there are decisions supporting national well-being (largely economics) that all countries engage in, pushing the set of rules that help them the most.

Discussions of China’s cyberspying have always been too isolated for discussions of China’s other national economic decisions. China steals just as much from US corporations located in China, but no one seems to care about that as a national security issue. And China buys a great deal, and has been buying a lot more of the things that it used to steal. The outcome is the same, yet we fetishize the method.

Which is why I find this so ironic.

A Chinese billionaire with party connections last year purchased the company, Wright USA, that insures a lot of national security officials in case they get sued or criminally investigated.

The company, Wright USA, was quietly acquired late last year by Fosun Group, a Shanghai-based conglomerate led by Guo Guangchang, a billionaire known as “China’s Warren Buffett” who has high-level Communist Party connections.

The links between Guo and Wright USA came under scrutiny by the Treasury Department’s Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, as well as the Office of Director of National Intelligence, the coordinating body of all U.S. spy agencies, soon after Fosun announced the purchase of Wright’s parent company last November. The FBI has also launched a criminal probe into whether the company made “unauthorized disclosures of government data to outsiders,” according to a well-placed source, who like others, spoke to Newsweek on condition of anonymity because the information was sensitive.

(The FBI declined to comment, and Fosun denies the FBI has asked it for any documents.)

U.S. officials are concerned that the deal gave Chinese spy agencies a pipeline into the names, job titles, addresses and phone numbers of tens of thousands of American intelligence and counterterrorism officials—many working undercover—going back decades.

This happened after the Chinese acquired via the kind of cybertheft everyone seems to agree is old-fashioned spying the medical records and clearance records of most of Americans cleared personnel. And yet a Chinese firm was able to buy something equally compromising right out from underneath the spooks who oversee such things.

China will get what it wants via a variety of means: stealing domestically when Americans come to visit, stealing via hack, or simply buying. That we treat these differently is just a fetish, and one that seems to blind us to the multiple avenues of threat.