Rosemary Collyer’s Worst FISA Decision

In addition to adding former National Security Division head David Kris as an amicus (I’ll have more to say on this) the FISA Court announced this week that Rosemary Collyer will become presiding judge — to serve for four years — on May 19.

Collyer was the obvious choice, being the next-in-line judge from DC. But I fear she will be a crummy presiding judge, making the FISC worse than it already is.

Collyer has a history of rulings, sometimes legally dubious, backing secrecy and executive power, some of which include,

2011: Protecting redactions in the Torture OPR Report

2014: Ruling the mosaic theory did not yet make the phone dragnet illegal (in this case she chose to release her opinion)

2014: Erroneously freelance researching the Awlaki execution to justify throwing out his family’s wrongful death suit

2015: Serially helping the Administration hide drone details, even after remand from the DC Circuit

I actually think her mosaic theory opinion from 2014 is one of her (and FISC’s) less bad opinions of this ilk.

The FISC opinion I consider her most troubling, though, is not a FISC decision at all, but rather a ruling from last year in an EFF FOIA. Either Collyer let the government hide something that didn’t need hidden, or it has exploited EFF’s confusion to hide the fact that the Internet dragnet and the Upstream content programs are conducted by the same technical means, a fact that would likely greatly help EFF’s effort to show all Americans were unlawfully spied on in its Jewell suit.

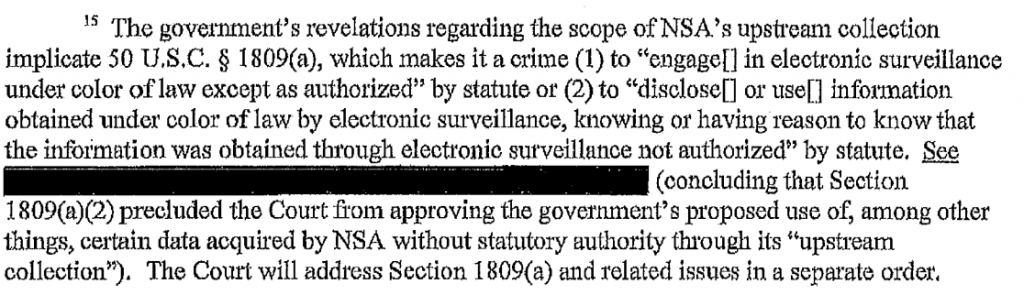

Back in August 2013, EFF’s Nate Cardozo FOIAed information on the redacted opinion referred to in this footnote from John Bates’ October 3, 2011 opinion ruling that some of NSA’s upstream collected was illegal.

Here’s how Cardozo described his FOIA request (these documents are all attached as appendices to this declaration).

Accordingly, EFF hereby requests the following records:

1. The “separate order” or orders, as described in footnote 15 of the October 3 Opinion quoted above, in which the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court “address[ed] Section 1809(a) and related issues”; and,

2. The case, order, or opinion whose citation was redacted in footnote 15 of the October 3 Opinion and described as “concluding that Section 1809(a)(2) precluded the Court from approving the government’s proposed use of, among other things, certain data acquired by NSA without statutory authority through its ‘upstream collection.’”

Request 2 was the only thing at issue in Collyer’s ruling. By my read, it would ask for the entire opinion the citation to which was redacted, or at least identification of the case.

EFF, of course, is particularly interested in upstream collection because it’s at the core of their many years long lawsuit in Jewell. To get an opinion that ruled upstream collection constituted unlawful collection sure would help in EFF’s lawsuit.

In her opinion, Collyer made a point of defining “upstream” surveillance by linking to the 2012 John Bates opinion resolving the 2011 upstream issues (as well as to Wikipedia!), rather than to the footnote he used to describe it in his October 3, 2011 opinion.

The opinion in question, referred to here as the Section 1809 Opinion, held that 50 U.S.C. § 1809(a)(2) precluded the FISC from approving the Government’s proposed use of certain data acquired by the National Security Agency (NSA) without statutory authority through “Upstream” collection. 3

3 “Upstream” collection refers to the acquisition of Internet communications as they transit the “internet backbone,” i.e., principal data routes via internet cables and switches of U.S. internet service providers. See [Caption Redacted], 2012 WL 9189263, *1 (FISC Aug. 24, 2012); see also https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Upstream_collection (last visited Oct. 19, 2015); https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_backbone (last visited Oct. 19, 2015).

As it was, Collyer paraphrased where upstream surveillance comes from as ISPs rather than telecoms, which was redacted in the opinion she cited. But by citing that and not Bates’ 2011 opinion, she excluded an entirely redacted sentence from the footnote Bates used to explain it, which in context may have described a little more about the underlying opinion.

Having thus laid out the case, Collyer deferred to NSA declarant David Sherman’s judgment — without conducting a review of the document — that releasing the document would reveal details about the implementation of upstream surveillance.

Specifically, the release of the redacted information would disclose sensitive operational details associated with NSA’s “Upstream” collection capability. While certain information regarding NSA’s “Upstream” collection capability has been declassified and publicly disclosed, certain other information regarding the capability remains currently and properly classified. The redacted information would reveal specific details regarding the application and implementation of the “Upstream” collection capability that have not been publicly disclosed. Revealing the specific means and methodology by which certain types of SIGINT collections are accomplished could allow adversaries to develop countermeasures to frustrate NSA’s collection of information crucial to national security. Disclosure of this information could reasonably be expected to cause exceptionally grave damage to the national security.

[snip]

With respect to the FISC opinion withheld in full, it is my judgment that any information in the [Section 1809 Opinion] is classified in the context of this case because it can reasonably be expected to reveal classified national security information concerning particular intelligence methods, given the nature of the document and the information that has already been released. . . . In these circumstances, the disclosure of even seemingly mundane portions of this FISC opinion would reveal particular instances in which the “Upstream” collection program was used and could reasonably be expected to encourage sophisticated adversaries to adopt countermeasures that may deprive the United States of critical intelligence. [my emphasis]

Collyer found NSA had properly withheld the document as classified information the release of which would cause “grave damage to national security.”

Now, especially thanks to Thomas Hogan’s November 6, 2015 Section 702 certification approval opinion released last week, we have a fair amount of detail about opinions addressing 50 U.S.C. §1809(a)(2) violations written before October 3, 2011 (this post and this post lay some of that out). These are the three possibilities to explain what that prior memo is.

One possibility is that the May 13, 2011 opinion titled “Opinion and Order Requiring Destruction of Information Obtained by Unauthorized Electronic Surveillance” (see page 57), described in that Hogan opinion, is that opinion. NSA left unredacted Hogan’s description of a “Title I collection in a particular case,” and made it clear that in that individual case, NSA collected data it was not authorized to collect. Hogan did not identify the problem as an upstream violation, though it would be unremarkable for every individual electronic surveillance order to include upstream surveillance, to collect the online behavior of a target outside of PRISM producers, as it would be equally unremarkable to target jihadist forums and the like using upstream surveillance. An order using multiple methods to target the same identifier might explain why Bates described the opinion as relating to “among other things, certain data acquired by NSA without statutory authority through its ‘upstream collection.’” But the timing would be particularly curious, given that NSA submitted the first clarification letter revealing its upstream 702 violations on May 2, before the final opinion in the individual case got finalized.

If that’s the opinion that NSA said would cause grave damage to national security, it seems odd that less than a year after Collyer’s ruling, NSA decided they can now segregate information from the opinion (I assume they didn’t mean to leave the title of the opinion unredacted, but as far as I know NYC has not collapsed as a result).

Another possibility is that the redacted opinion is the July 2010 John Bates opinion that spends its last 18 pages (98-116) discussing the application of 50 USC §1809(a)(2) to NSA surveillance. A December 2010 opinion leading up to the May 13, 2011 one cites from it at length (Hogan cites from that opinion at 57), and Hogan himself cited from it at length two more times (73 fn 54, 76 fn 56). In 2013, I assumed that’s what Bates’ later reference was to, and I still think it most likely, as it has become clear that that July 2010 opinion is the base opinion laying out how FISC applies 50 USC §1809(a)(2) to NSA surveillance that has gotten a little bit out of hand. In any case, those 18 pages are what EFF was looking for in the first place, the opinion on how NSA applies this law; they just somehow missed it in a critical opinion on PRTT.

The counterargument that this is the opinion in question is three-fold. First, Bates says that the memo he was citing from pertains to upstream surveillance, and we’ve been led to think of the Internet dragnet as a simple pen register.

Except that we know it is a “pen register” applied to telecom switches. There are few explicit explanations of this in officially released NSA documents, but in places — such as when Bates explains his inconceivable approval to expand this collection after railing about 5 years of violations — he makes clear that “Acquisition of particular forms of metadata (described in Part II, supra) is authorized for all e-mail [redacted] communications traversing any of the communications facilities at the specified locations.” (81) It’s more clear that upstream surveillance expanded on this PRTT collection from application documents (see DOJ’s supplemental memorandum at PDF 93) to conduct upstream collection to replace Stellar Wind, which cite Colleen Kollar-Kotelly’s 2004 PRTT opinion finding telecom switches were a facility under the term of the FISA pen/trap and trace provision, though the reference to switches seems to cite from this paragraph, which is redacted in the original.

Bates even makes it clear this PRTT collection can involve the collection of content when he talks about criminal decisions on whether the government could collect and then delete Post Cut Through Direct Dial content from a Pen Register (though curiously he may not cite earlier 2009 FISC discussions about its own permission to collect then minimize such information).

This discussion makes two things clear: first, PRTT is upstream collection; it’s what upstream content collection pointed to as precedent for switches being treated as FISA “facilities.” But in its public releases, NSA has tried to hide the fact that is is. I’ll come back to that.

Another counterargument that this is the opinion is that it has already been released!!! The opinion was released in response to an EPIC FOIA in November 2013 and EFF started suing for it in May 2014 (it was “randomly” assigned to Collyer, who started service as a FISC judge in March 2013, in June 2014).

It is not without precedent for the government to play funny games with FOIAs. I’ve noted how the NSC withheld the Memorandum of Notification underlying the war on terror without ACLU realizing, at first, that’s what they were arguing over. A more exact analogy is is how, in another ACLU FOIA, the government has pretended that the Special Procedures for Communications Metadata Analysis have not been released (though they were released again yesterday, along with some of the underlying language they’re trying to hide from ACLU) so as to avoid having to release the underlying justification memo.

Of potentially critical import, along the way (I believe in early 2015), EFF agreed not to ask for the docket information or date of the opinion.

Plaintiff narrowed its challenges here to exclude (1) docket numbers, certification numbers and the like, (2) all withholdings pursuant to exemption (b)(6), and (3) names or descriptions of surveillance targets, all that remains in dispute are withholdings of classified intelligence sources and methods and law-enforcement procedures and methods that are exempt under (b)(1), (b)(3), and (b)(7).

The government is, after all, hiding both the docket number and date of the July 2010 memo (significantly, they’re also hiding the dates of the 2009 PRTT violations that resulted in a shut-down of PRTT collection at moments that coincide in key ways with EFF’s challenges to the NSA program). The only thing they’ll tell us that it was shut down and (they claim, though even NSA’s IG couldn’t entirely verify this) purged all the data very quickly in the weeks after Bates ruled the upstream collection was unconstitutional in 2011. So there’s no way we can prove (except for basic analysis and the fact they accidentally released the July 2010 date to Charlie Savage in a FOIA) that the PRTT opinion, which is technically upstream collection, predates the October 3, 2011 one. And the government can avoid having to convince Collyer that these dates and dockets are a key operational detail (which they’re not) even while they withhold the few tidbits that would make it clear the July 2010 memo is the one responsive to EFF’s FOIA.

The final counterargument for why the July 2010 memo is not the one in question is that it would make Bates’ syntax about the “government’s proposed use of, among other things, certain data acquired by NSA without statutory authority through its ‘upstream collection’” rather curious. All the data he ruled against the use of was acquired from switches, although some of it was legal. Moreover, unless the category violations of Kollar-Kotelly’s 2004 order were far broader than what Bates approved in his July 2010 opinion, then he ultimately found they had the statutory authority, just not the authority granted by the court (effectively because Bates redefined Dialing, Routing, Addressing, or Signaling information more broadly in 2010).

Of course, there’s a third possibility, that the opinion in question is a third one, one we’ve never heard of yet. The biggest reason I think that unlikely is that July 2010 does appear to be the base discussion of 50 USC §1809(a)(2) (it doesn’t, for example, cite any earlier discussion). Which would mean any other 50 USC §1809(a)(2) opinion would come in the fairly narrow window between July 2010 and October 2011. That’d be a lot of opinions (along with the May 2011 one) finding that NSA was illegally wiretapping Americans. Moreover, I would think a third opinion ruling what is technically upstream collection illegal would get even more discussion in Bates’ 2011 opinion.

As I said, I think it’s most likely that the government — with Collyer’s assistance — is hiding the fact that that 2010 opinion is the one Bates cited in his 2011 opinion. Sherman’s explanation that the information was classified “in the context of this case … given the nature of the document and the information that has already been released” would support an understanding that NSA refused to tell EFF that the already released 2010 opinion is the one they were looking for all along so as to hide the fact that PRTT is nothing more than upstream collection. In that case, the opinion itself wouldn’t be classified, just acknowledgment that that’s what Bates meant as precedent when he found other kinds of upstream collection unconstitutional in 2011.

There is a very obvious reason why they’d want to do that. The government has argued in EFF’s suits that upstream 702 collection does not infringe on the rights of Americans because the telecoms sort it before they hand it over to NSA. The only things that get handed over are transactions including the selector in question; the selectors are by definition foreign; and the switches from which they collected are supposed to be foreign facing. Crucially, the government has argued that because the telecoms and not the government does the upstream search, it doesn’t amount to governmental violation.

None of those things are true of PRTT collection. Even in 2004, when Kollar-Kotelly limited collection to switches that were more likely to include terrorism traffic, the collection was designed to include all the metadata of Americans’ international conversations from those switches. In 2010, Bates expanded the number of switches NSA collected from, affecting a far greater percentage of Americans. He also expanded what could be collected from a packet to include stuff that is technically content (though the violations revealed in 2009 make it clear NSA was always collecting what is technically content under the Internet dragnet, and that’s probably why it was such a problem under Stellar Wind). Furthermore, when NSA did intake for bulk collected metadata — as distinct from when they intake content — they put everything into a table of relationships. The analysts will never see the majority of this data, but effectively, the first thing the techs did on intake of PRTT data was conduct a search of every single record they obtained.

I strongly believe this is why NSA did not permit its IG to review the intake part of the PRTT process when they destroyed it all in 2011, because it might have revealed that they were effectively illegally searching content-as-metadata from all Americans as part of the intake process.

EFF may not win their argument that upstream content collection is an illegal search. But (perhaps counterintuitively) they should be more likely to make that argument for PRTT, not least because NSA shut it down entirely on two different occasions, at least the first time and quite possibly the second because it was violating FISA orders.

And that is why I believe NSA wants to avoid admitting that that 2010 PRTT opinion is technically about unlawful upstream collection: because it would make it far easier for EFF to win their lawsuits against the government. They were granted discovery in February, so hopefully they can get to this information in any case. But I strongly suspect the NSA withheld a document it had already released only to make it harder for EFF to prove that even after PRTT moved under FISA’s oversight, it continued to be illegal collection for 5 years and then one more year, even as determined by John Bates.

And NSA did all this with the cooperation of a FISA judge they happened to “randomly” pull for this case, one who should have known enough by the point she ruled to understand the stakes. That is why I think Collyer will be a crummy FISC judge. Even if this FOIA suit was about the May 2011 opinion, it clearly was improperly withheld. But if it was about the already released July 2010 one, then it suggests a real abuse of authority.

Two years ago, I noted that we effectively have gotten to the point where we have a one (wo)man national security court, because the presiding judge (and maybe one or two other DC-based judges) sit on the big programmatic cases. That’s particularly problematic when, as now, we have a particularly crummy judge from a constitutional perspective.