The Steele Dossier broke America.

Not literally. Nearly three decades of Fox News, increasing wealth inequality, and unlimited money in politics likely did that.

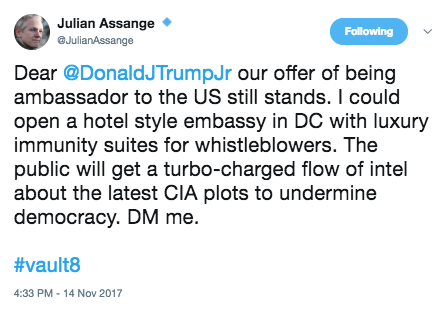

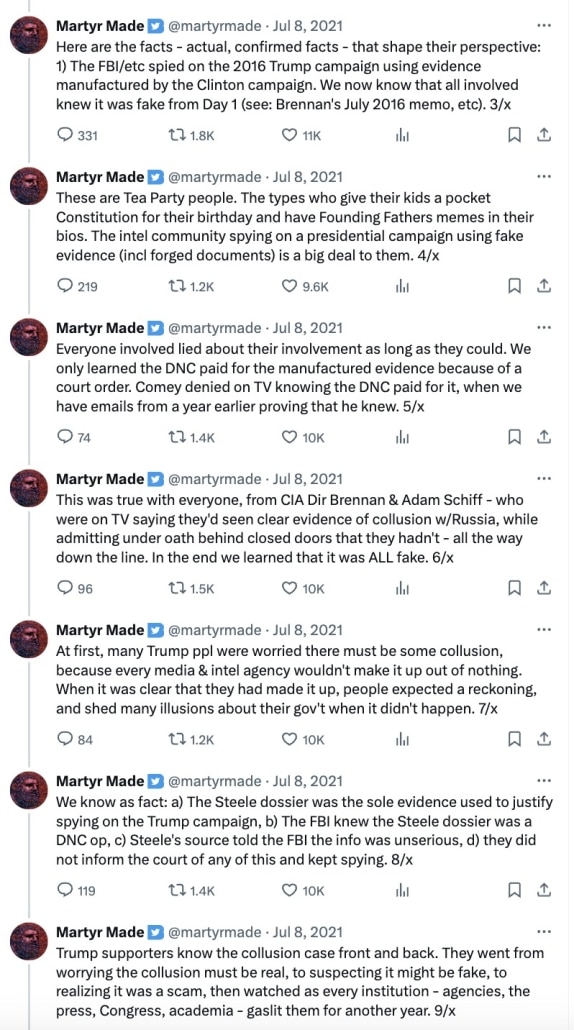

But there are MAGAts who blame much of it on the dossier. There are MAGAts who situate their own shift in allegiance from the country to Trump based on a false belief that the dossier was part of a devious plot between Hillary Clinton and the Deep State to frame Donald Trump. That’s a key part of this thread from a right wing podcaster excusing January 6, which went viral just days after the attack.

Such views — mixing accurate criticism of the dossier with wild conspiracy theories — really did play a key role in polarizing the US. Phil Bump explained how the adoption of such conspiracy theories (which he fact checked) worked in real time. And I noted that if, as virtually all Republican members of Congress who spent years investigating the dossier concluded, it was riddled with Russian disinformation, it means MAGAts attacked their own country in response to Russian disinformation.

This didn’t happen by accident. Instead, it likely involved a brilliant multi-step disinformation campaign victimizing everyone: Hillary, Paul Manafort and Trump, and even the Deep State.

The first step was a brutal double game Oleg Deripaska deployed: using his tie to Christopher Steele to add to Paul Manafort’s legal insecurity — or perhaps to hide his own role in election interference by offering himself as a potential cooperator — even while using that insecurity to win cooperation from Trump’s campaign manager on the election attack.

The next step was, apparently, injecting garbage into the Steele dossier, some near misses that obscured the real attack and made Trump’s people less secure.

The third was an effort, partly deliberate and then later partly organic (albeit often on the part of credulous people who published obviously false claims from Konstantin Kilimnik), to conflate the dossier with the entire Russian investigation. Along the way MAGAt politicians, both right wing and quasi-lefty influencers, and even established journalistic institutions would join this effort. Because the dossier was unreliable, because it was used in the investigation of Carter Page (a guy already under scrutiny when he joined the Trump campaign) — this sustained propaganda campaign insisted — all the reporting on the Russian attack, the FBI investigation into it, and the results must be nought.

By substituting the dossier for the rest of the Russian investigation, this propaganda effort flipped Trump’s enthusiasm for foreign interference in democracy on its head, and allowed him — the guy who invited Russia to hack his opponent — to play the victim.

Deripaska’s double game

The first part of this process has gotten the least attention (indeed, Republican conspiracy theories covered it up).

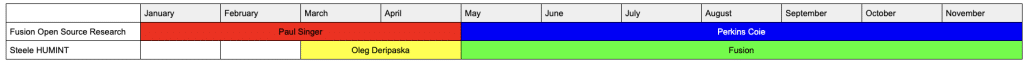

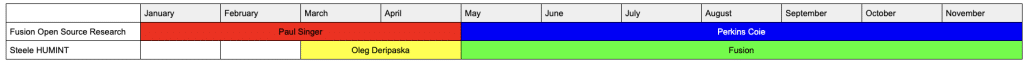

There were two parts of the intelligence collection on Trump and his associates: with a few notable exceptions, accurate open source research done by Fusion GPS itself, and raw HUMINT collection from former MI6 officer Christopher Steele that may have been injected with disinformation. It has long been public that right wing billionaire Paul Singer indirectly paid for the open source research during the GOP primary, only to have the Democrats pick up the project during the general election.

What’s not widely known is that starting in March — the same month Manafort was publicly hired by the campaign (though, according to Sam Patten, Konstantin Kilimnik expected that to happen before it was public) — Deripaska paid Steele, through an attorney, to collect on Manafort.

[Steele’s] initial entree into U.S. election-related material dealt with Paul Manafort’s connections to Russian and Ukrainian oligarchs. In particular, Steele told the FBI that Manafort owed significant money to these oligarchs and several other Russians. At this time, Steele was working for a different client, Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska.

And Steele paid Fusion to help with this effort. So before May, Deripaska paid Steele, who paid Fusion. After May, Democrats paid Fusion, which paid Steele.

But, as Igor Danchenko described, that earlier effort to collect on Manafort met with little success.

[H]e may have asked friends and contacts in Russia [for information on Manafort], but he couldn’t remember off-hand. He added that, for this topic, his friends and contacts in Russian couldn’t say very much because they were “too far removed” from the matter.

It was after that, on a trip Danchenko took to Russia, when Steele asked Danchenko to “look for information dealing with the US presidential election, including compromising materials on Donald Trump.”

Probably as a result of this close relationship, by July, intelligence reporting later assessed, one of Deripaska’s associates was probably aware of the DNC dossier project. Similarly, reporting found that, “two persons affiliated with [Russian Intelligence Services] were aware of Steele’s election investigation in early 2016.” As I have, John Durham linked these two reports, suggesting a likelihood that the Russian spooks had ties to Deripaska (though in making that link, Durham obscured Deripaska’s identity). Given Deripaska’s own alleged ties to Russian intelligence, if his lawyer knew and he knew, spooks close to him — including, allegedly, Kilimnik — would likely have known. Durham also described that Russian intelligence had identified Steele’s subsource network.

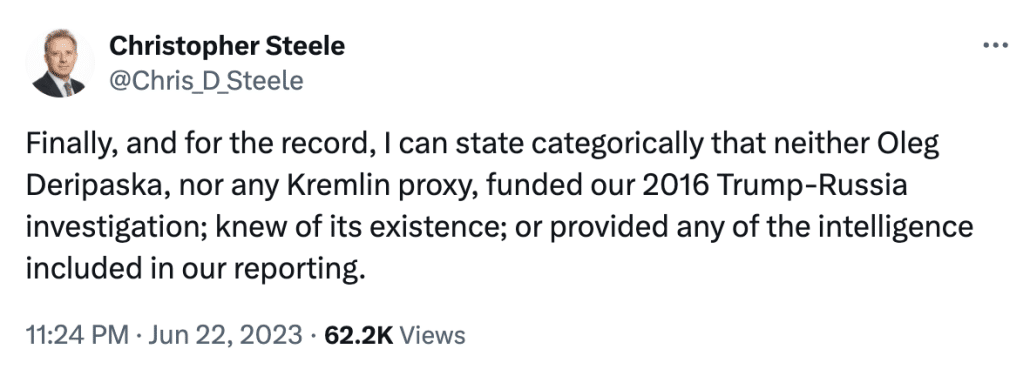

Paul Manafort’s former boss, Oleg Deripaska, probably knew about the dossier project in close to real time.

Christopher Steele denies that’s the case.

If Deripaska did know of the project, though, it dramatically changes the significance of a meeting Christopher Steele had with Bruce Ohr, then a top lawyer coordinating DOJ’s effort to combat multinational organized crime, in late July 2016. Steele had been trying to pitch Ohr to recruit oligarchs purportedly willing to cooperate against Russia. He had, earlier in 2016, assured Ohr that Deripaska had distanced himself from Putin. Earlier in July, he contacted Ohr about Deripaska.

Steele thought Deripaska could be trusted.

And on July 30, between the time Konstantin Kilimnik flew to Moscow to prepare for his Paul Manafort meeting and when he arrived in New York for that meeting, Steele met with Ohr in DC.

For years, Republicans claimed that this was an instance of Steele working every contact he had at FBI and DOJ to make sure his dossier reports got shared. Except Steele did more than share dossier leads at that meeting (one, about what Russian spooks had reportedly said about Trump, the other about whom Carter Page might have met with in Moscow). In addition, he shared information about Russian doping, a topic on which Steele reportedly had a good track record.

And most importantly, Steele pitched information from Deripaska about Paul Manafort (this is from Ohr’s testimony to Congress).

Mr. Ohr. So Chris Steele provided me with basically three items of information. One of them I’ve described to you already, the comment that information supposedly stated and made by the head, former head of the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service.

He also mentioned that Carter Page had met with certain high-level Russian officials when he was in Moscow. My recollection is at that time, the name Carter Page had already been in the press, and there had been some kind of statement about who he had met with when he went to Moscow. And so the first item that I recall Chris Steele telling me was he had information that Carter Page met with higher-level Russian officials, not just whoever was mentioned in the press article. So that was one item.

And then the third item he mentioned was that Paul Hauser, who was an attorney working for Oleg Deripaska, had information about Paul Manafort, that Paul Manafort had entered into some kind of business deal with Oleg Deripaska, had stolen a large amount of money from Oleg Deripaska, and that Paul Hauser was trying to gather information that would show that, you know, or give more detail about what Paul Manafort had done with respect to Deripaska.

[snip]

Q Were there any other topics that were discussed during your July 30, 2016, meeting?

A Yes, there were. Based on my sketchy notes from the time, I think there was some information relating to the Russian doping scandal, but I don’t recall the substance of that.

When I first understood how this worked together, I thought that Deripaska was primarily doing this to increase Paul Manafort’s legal exposure, making Manafort more vulnerable when Deripaska, via Kilimnik, started making asks in a cigar bar days later. It certainly may have increased the chance that the FBI would develop the criminal investigation into Manafort.

But it likely did another thing: it likely made the FBI more interested in treating Deripaska as a source, rather than a subject. And sure enough, in September 2016, the FBI interviewed Deripaska, at which interview (John Solomon parroted in advance of Robert Mueller’s testimony, during the period Solomon was a key player in Rudy Giuliani’s information operation) he scoffed that Manafort would have any tie to Russia.

“I told them straightforward, ‘Look, I am not a friend with him [Manafort]. Apparently not, because I started a court case [against him] six or nine months before … . But since I’m Russian I would be very surprised that anyone from Russia would try to approach him for any reason, and wouldn’t come and ask me my opinion,’ ” he said, recounting exactly what he says he told the FBI agents that day.

“I told them straightforward, I just don’t believe that he would represent any Russian interest. And knowing what he’s doing on Ukraine for the last, what, seven or eight years.”

As I’ve written, much of the outreach to Trump’s associates in 2016 involved people who had served as FBI sources. Deripaska knew Steele spoke with the FBI. People like Sergei Millian and Felix Sater had been FBI sources. More recently, of course, Alexander Smirnov allegedly attempted to frame Joe Biden.

A key tactic of this effort was to exploit FBI’s HUMINT efforts, to use FBI’s informants against it. So much so that Deripaska even feigned cooperation with the FBI himself!

The dossier would become an important part of — largely constructed — stories about the Russian investigation. But that all lay on top a foundation of efforts Deripaska made to use Christopher Steele to set up (and maybe even obscure) his asks of Paul Manafort.

A series of near misses

The knowledge that Deripaska and Russian spooks had of Steele’s network and the ongoing Fusion GPS project would have provided the means to plant disinformation.

As noted above, for a period, every one of the Republicans who examined the dossier at length concluded that Russia had succeeded in filling the dossier with disinformation. Lindsey Graham — who conducted an investigation into the circumstances of the Carter Page FISA — said it did. Chuck Grassley — who led the investigation into the dossier — said it did. Ron Johnson — who also made a show of investigating these things — said it did. Chuck Ross — the chief scribe of the dossier on the right — said it did. The high gaslighter Catherine Herridge said it did. Fox News and all their favorite sources said it did. WSJ’s editorial page said it did.

Then, they stopped saying it.

Maybe they thought through the implication of it being Russian disinformation. Maybe they started looking to John Durham’s efforts to blame Hillary Clinton by fabricating conspiracy theories instead.

Because, think about it: Unlike Rudy Giuliani, there’s no hint that Hillary set out to collect dirt that would be easily identifiable to the campaign as disinformation. She had no reason to seek inaccurate information; the reality was already damning enough.

“For us to go out and say a bunch of things that aren’t true, you know, can cause a lot of damage to the campaign,” Hillary Campaign Manager Robby Mook testified in the Michael Sussmann trial.

Hillary gained nothing by paying a lot of money for a project riddled with disinformation. Russian spooks simply took advantage of something every politician does — collect oppo research — to harm her, harm Carter Page, and harm the US.

Consider the effect it may have had (I examine the reports one by one here).

One effect possible disinformation may have had was to make Hillary complacent as she struggled to deal with a hack during the height of the campaign. For example, several of Steele’s reports said any kompromat Russia had on Hillary consisted of very dated intercepts, not recently-stolen emails. One report falsely claimed Russia hadn’t had success at hacking Western targets. Later reports provided purported updates on the hack-and-leak campaign, suggesting Russia was dropping any further efforts, that directly conflict with ongoing developments. Subsequent investigation showed those reports were all false.

And every one of those reports might have led Democrats (and the FBI) to be complacent about ongoing risks posed by the hack they had IDed in April (and indeed, they didn’t expect the files stolen from the DNC to be released).

Another report which could be disinformation (but which, if you can believe Danchenko, may also be Steele exaggeration of very tepid things he said about someone he believed to be Sergei Millian), would be to shield Konstantin Kilimnik’s role in the election interference. One of the most important reports for what came afterwards alleged that the,

“well-developed conspiracy of cooperation” between Trump’s team and Russian leadership “was managed on the TRUMP side by the Republican candidate’s campaign manager, Paul MANAFORT, who was using foreign policy advisor, Carter PAGE and others as intermediaries.

If Page was Manafort’s go-between, no one would look at what Kilimnik was doing.

To be sure, this could be Steele’s doing. It appears in a report that misrepresented what Danchenko claims to have told Steele about his contacts with Sergei Millian.

And as the Senate Intelligence Committee Report noted — I hope, sardonically — nothing about Manafort’s ties to Deripaska (or Kilimnik) ever made it into the dossier.

Steele and his subsources appear to have neglected to include or missed in its entirety Paul Manafort’s business relationship with Deripaska, which provided Deripaska leverage over Manafort and a possible route of influence into the Trump Campaign.

Steele mentions Paul Manafort by name roughly 20 times in the dossier, always in the context of his work in Ukraine; and, in particular, Manafort’s work on behalf of then-Ukrainian President Victor Yanukovych. Deripaska, who had a long-standing business relationship with Manafort, is not mentioned once. Neither is Kilimnik, Manafort’s right-hand man in Kyiv, who himself has extensive ties to Deripaska. 5885 Despite Steele’s expertise on Ukraine and Russia, particularly on oligarchs, the dossier memos are silent on the issue.

Whatever the explanation — Danchenko’s failures to get dirt, Steele’s efforts to protect another contract, or disinformation — the dossier’s failure to note Kilimnik’s role (along with its silence about Natalia Veselnitskaya’s pitch of dirt to Don Jr. and George Papadopoulos’ shenanigans in London) effectively distracted from the most glaring signs of Trump ties with Russia. It served as camouflage. The things that don’t show up in the dossier that Fusion and Steele should have learned were almost as useful to the Russian project as the near-misses that did.

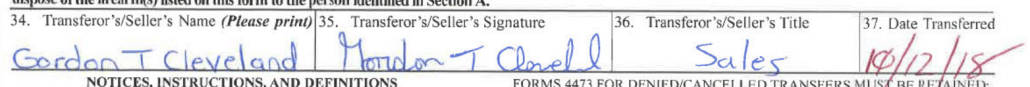

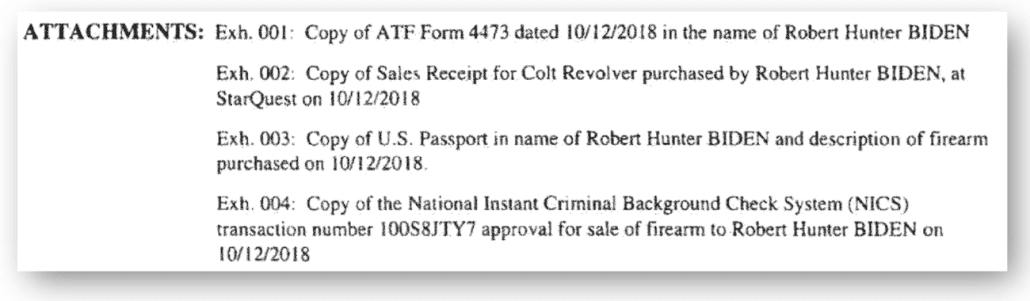

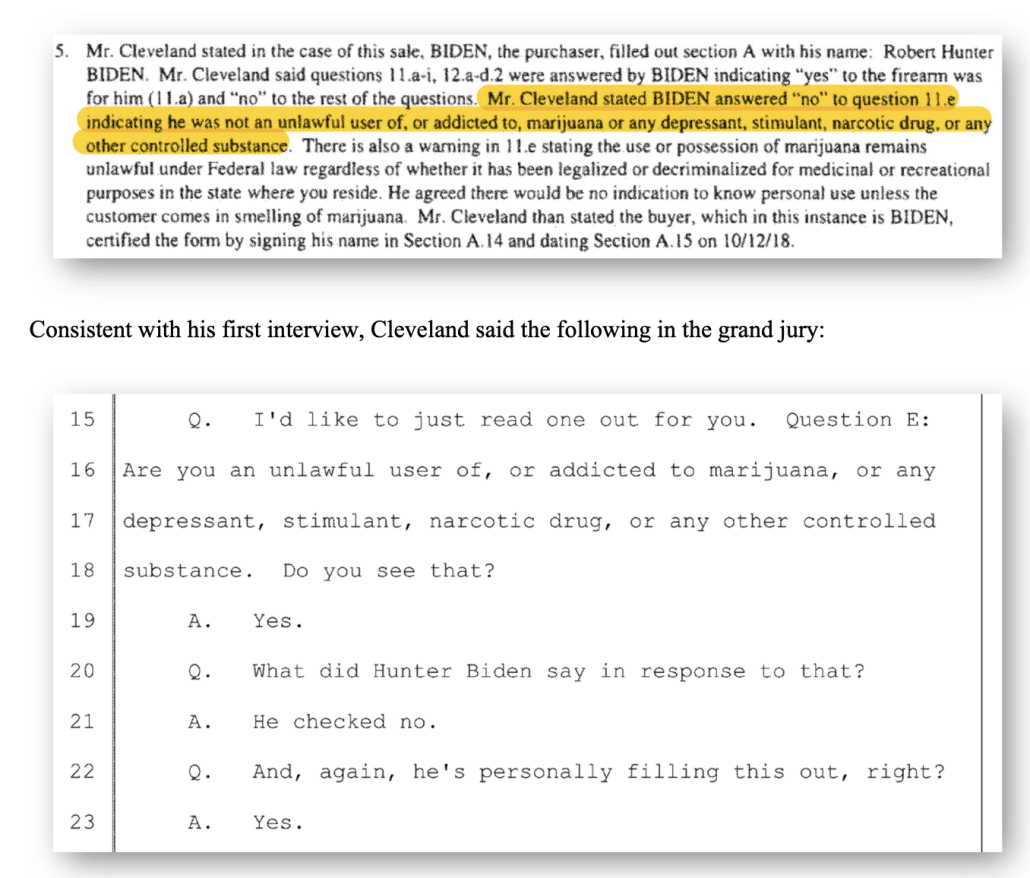

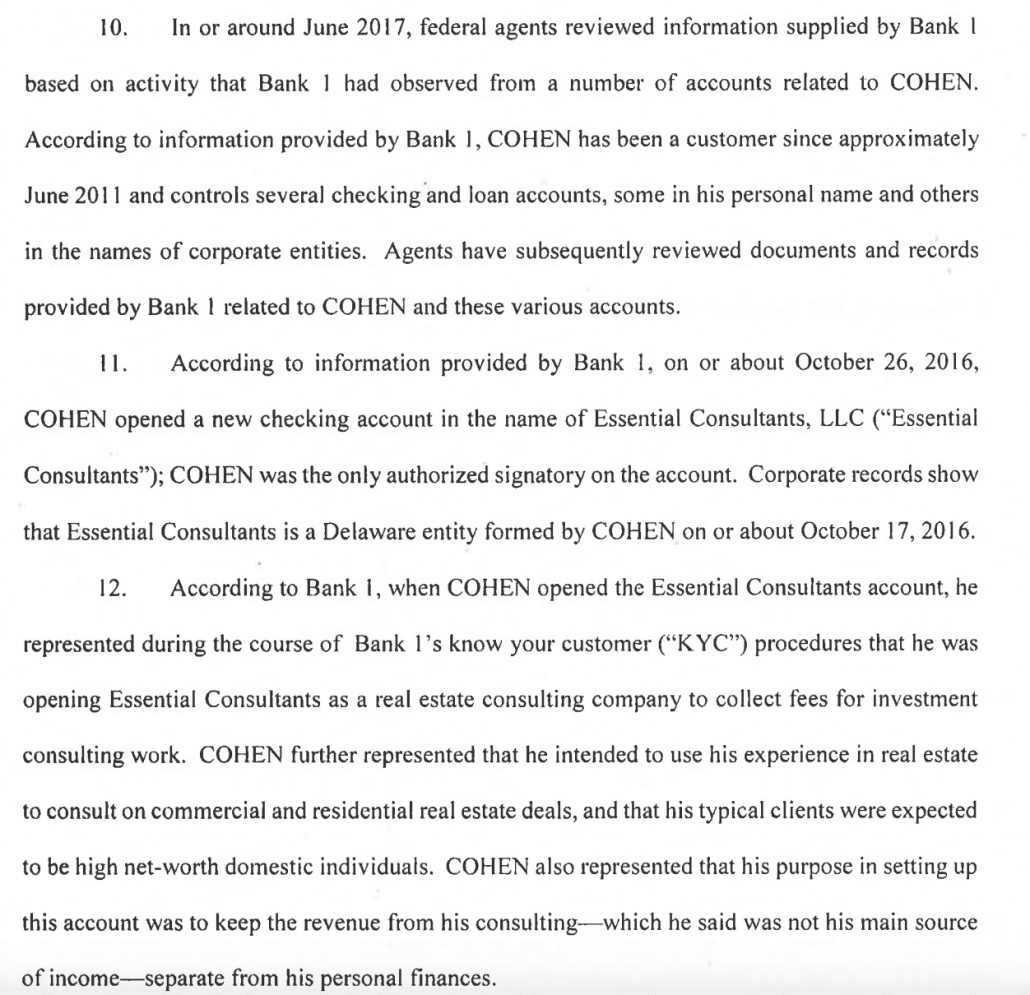

Perhaps the best established case of disinformation, however, is a tribute to its usefulness. Starting in October 2016 (in the period Michael Cohen was frantically cleaning up Trump’s Stormy Daniels problem), Steele produced first three (one, two, three), and then, in December 2016, a fourth report alleging that Michael Cohen was instead cleaning up the alleged coordination between Manafort and the Russians. Each report got progressively more inflammatory, with the last one alleging that Cohen and three associates went to Prague in August or September for secret discussions with the Kremlin and its hackers; the discussion allegedly involved cash payments to operatives and plans to cover up the operation.

If true, this would have been a smoking gun.

Within weeks of the last report, on January 12, 2017 — two days after Buzzfeed published the dossier — the Intelligence Community got intelligence assessing that it was disinformation.

January 12, 2017, report relayed information from [redacted] outlining an inaccuracy in a limited subset of Steele’s reporting about the activities of Michael Cohen. The [redacted] stated that it did not have high confidence in this subset of Steele’s reporting and assessed that the referenced subset was part of a Russian disinformation campaign to denigrate U.S. foreign relations.

Of course, that was not made public for over three years. As a result, even as the story of Mike Flynn’s attempts to undermine Obama’s foreign policy rolled out, even as Cohen was accepting big payments from Viktor Vekselberg, the Cohen-in-Prague story became the measure of so-called collusion.

From the start of the public accounting of Trump’s ties to Russia, then, something the IC already understood to be likely disinformation was the yardstick of the Russian investigation.

Two aspects of the story make it especially ripe to be intentional disinformation, in form and content.

First, according to Danchenko, the Cohen story came from his childhood friend, Olga Galkina, who knew he worked in some kind of intelligence collection and who even tried to task him to collect information after the dossier came out.

In March of 2016, Danchenko had introduced PR executive Chuck Dolan to her. Dolan and Danchenko traveled the same DC-based circles of Russian experts, and she was looking for the kind of public affairs consulting that Dolan offered, on behalf of her company. Over the course of two trips to Cyprus as part of that business, Dolan and Galkina developed an independent relationship. Dolan’s company was at the same time working on a business development project for the Russian government, in which he directly interacted with Dmitry Peskov’s office. Through that networking, on July 13, 2016, Galkina claimed that Dolan had recommended her for a job with Peskov’s office (he told Durham’s prosecutors he didn’t remember this when they asked). And on October 15, 2016 — in the same week that she first shared the Cohen story with Danchenko — Galkina gossiped about knowing something via Peskov’s office.

On October 15, 2016, Galkina communicated with a Russia-based journalist and stated that because of her [Galkina] “acquaintance with Chuck Dolan and several citizens from the Russian presidential administration,” Galkina knew “something and can tell a little about it by voice. ” 882

As Danchenko told the FBI, when he asked Galkina if she knew anything about several people on whom Steele had tasked him to collect, Michael Cohen’s name was the single one she recognized.

[Danchenko] began his explanation of the Prague and Michael Cohen-related reports by stating that Christopher Steele had given him 4-5 names to research for the election-related tasking. He could only remember three of the names: Carter Page, Paul Manafort and Michael Cohen. When he talked to [Galkina] in the fall of 2016 — he believes it was a phone call — he rattled off these names and, out of them, he was surprised to her that [Galkina] [later [Danchenko] softened this to “almost immediately] recognized Cohen’s name. [bold brackets original]

After that initial conversation, Danchenko asked Galkina to go back to her sources for more detail, which resulted in several more reports.

In other words, the source for the allegation that Michael Cohen, in an attempt to cover up a Trump scandal, had direct ties to the Presidential Administration — the Kremlin — is someone who had developed direct and lucrative ties to Dmitry Peskov’s office, and had been bragging about having dirt involving Peskov’s office that very week.

And Dmitry Peskov is one person who undoubtedly knew that Michael Cohen had called the Kremlin nine months earlier, because Trump’s fixer had called Peskov’s own office.

In the wake of Trump’s public denial on July 27 that he had any ongoing business with Russia, and in the period when Cohen was busy covering up other Trump scandals, a story arose that alleged Cohen’s cover-up involved ties to the Kremlin.

As Robert Mueller would substantiate two years later, Cohen’s cover-up did involve a ties to the Kremlin, a call in which he solicited Putin’s help for a business deal involving a sanctioned bank and the GRU. But those were entirely different ties, in time and substance, from the ties claimed in the dossier.

This is the kind of near miss story — a story that approximated Cohen’s real contact with the Kremlin, which he and Trump were lying to hide, a story that approximated Cohen’s real efforts to cover up Trump’s scandals — that could serve both to distract and raise the risks of the public lies Cohen and Trump were telling to hide that Trump Tower deal, the lies that Dmitry Peskov knew Trump was telling.

It also proved useful when Cohen doubled down on his lies, in 2017. As I pointed out in real time, as the Trump Tower deal started to get leaked to the press (though without the most damning detail, that Cohen did succeed in reaching the Kremlin; Trump Organization withheld the email that proved that from Congress) Cohen used denials of the dossier allegations as a way to deny the burgeoning Trump Tower scandal as well. Because there was nothing to substantiate the Cohen-in-Prague story, Cohen’s then lawyer claimed, it meant there was no story at all.

The entire letter is pitched around the claim that HPSCI “included Mr. Cohen in its inquiry based solely upon certain sensational allegations contained” in the Steele dossier. “Absent those allegations,” the letter continues, “Mr. Cohen would not be involved in your investigation.” The idea — presented two weeks before disclosure of emails showing Cohen brokering a deal with Russians in early 2016 — is if Cohen can discredit the dossier, then he will have shown that there is no reason to investigate him or his role brokering deals with the Russians. Even the denial of any documents of interest is limited to the dossier: “We have not uncovered a single document that would in any way corroborate the Dossier’s allegations regarding Mr. Cohen, nor do we believe that any such document exists.”

With that, Cohen’s lawyers address the allegations in the dossier, one by one. As a result, the rebuttal reads kind of like this:

I Did Not Go to Prague I Did Not Go to Prague I Did Not Go to Prague I Did Not Go to Prague

Cohen literally denies that he ever traveled to Prague six times, as well as denying carefully worded, often quoted, versions of meeting with Russians in a European capital in 2016. Of course that formulation — He did not participate in meetings of any kind with Kremlin officials in Prague in August 2016 — stops well short of other potential ties to Russians. And two of his denials look very different given the emails disclosed two weeks later showing an attempt to broker a deal that Felix Sater thought might get Trump elected, including an email from him to one of the most trusted agents of the Kremlin.

Mr. Cohen is not aware of any “secret TRUMP campaign/Kremlin relationship.”

Mr. Cohen is not aware of any indirect communications between the “TRUMP team” and “trusted agents” of the Kremlin.

As I said above, I think it highly likely the dossier includes at least some disinformation seeded by the Russians. So the most charitable scenario of what went down is that the Russians, knowing Cohen had made half-hearted attempts to broker the Trump Tower deal Trump had wanted for years, planted his name hoping some kind of awkwardness like this would result.

That is, Cohen used his true denial of having been to Prague to rebut the equally true claim that he had contact with the Kremlin.

Manafort’s plan

There’s good reason to believe that Cohen’s focus was not an accident.

That’s because, after meeting with a Deripaska associate, Paul Manafort advised Trump to use precisely this approach.

In early January, Manafort met in Madrid with a Deripaska associate, Gregory Oganov. Manafort’s explanations to Mueller’s team about the purpose of the meeting vacillated (it was one of the topics about which Judge Amy Berman Jackson ruled he had lied). But according to a text from Kilimnik, the meeting was about recreating the old relationship he had had with Deripaska.

A May 2017 story from Ken Vogel (yeah, I know), described how after that trip, Manafort called Reince Priebus and told him that the dossier was full of inaccuracies, and that those inaccuracies — and the FBI’s reliance on Steele, the guy paid by a lawyer for Deripaska who brought claims about Manafort to DOJ — discredited the Russian investigation generally.

It was about a week before Trump’s inauguration, and Manafort wanted to brief Trump’s team on alleged inaccuracies in a recently released dossier of memos written by a former British spy for Trump’s opponents that alleged compromising ties among Russia, Trump and Trump’s associates, including Manafort.

“On the day that the dossier came out in the press, Paul called Reince, as a responsible ally of the president would do, and said this story about me is garbage, and a bunch of the other stuff in there seems implausible,” said a person close to Manafort.

[snip]

According to a GOP operative familiar with Manafort’s conversation with Priebus, Manafort suggested the errors in the dossier discredited it, as well as the FBI investigation, since the bureau had reached a tentative (but later aborted) agreement to pay the former British spy to continue his research and had briefed both Trump and then-President Barack Obama on the dossier.

Manafort told Priebus that the dossier was tainted by inaccuracies and by the motivations of the people who initiated it, whomhe alleged were Democratic activists and donors working in cahoots with Ukrainian government officials, according to the operative. [my emphasis]

Priebus shared Manafort’s comments with Trump.

Priebus did, however, alert Trump to the conversation with Manafort, according to the operative familiar with the conversation and a person close to Trump.

Notably, along with disputing that anyone with ties to Steele would know what Yanukovych would say to Putin, Manafort also debunked the claim that he was managing relations with Russia because he didn’t know Page.

In his conversation with Priebus, Manafort also disputed the assertion in the Steele dossier that Manafort managed relations between Trump’s team and the Russian leadership, using Page and others as intermediaries.

Manafort told Priebus that he’d never met Page, according to the operative.

As with Cohen’s later debunking of the Prague story to distract from the Trump Tower story, Manafort used a near miss in the dossier to discredit the larger true claim, that he had been working with someone in Russia.

Manafort met with Kilimnik personally in February, and according to Rick Gates, at Manafort’s behest, Kilimnik kept hunting down the other sources for the dossier. Of course, according to later intelligence reporting, Russian spooks already knew that.

How about that?

Within a day after the release of the dossier, at a time when he was meeting with an Oleg Deripaska deputy, Manafort came up with a strategy to discredit the entire Russian investigation by discrediting the dossier. How was Manafort so prescient about the faults of the dossier?

But Deripaska had almost certainly known about the dossier project for six months by that point, and had funded an earlier collection effort targeting Manafort himself.

And Republicans followed that strategy — to discredit the Russian investigation by discrediting the dossier and FBI’s decision to rely on Steele, a strategy Manafort shared after a meeting with a top Deripaska aide — for three years.

This post is part of a series describing how Trump trained Republicans to hate rule of law. Earlier posts include:

LOLGOP and I are doing a podcast series that closely follows this series.

Patreon

Apple Podcast

Spotify

The series builds on this background.