Seth Rich Conspiracists Liberate Records Showing DOJ Believes They’re Conspiracists

Some Seth Rich truthers — including Matthew Couch and Ed Butowsky — recently got some files in a FOIA on Seth Rich documents liberated. They succeeded in liberating files that show that a conspiracy theory they’ve been chasing is, in fact, easily explained based on how FOIA and time work.

On September 1, 2017, Ty Clevenger FOIAed for Seth Rich documents, including but not limited to everything about his murder. After Clevenger sued, FBI FOIA lead David Hardy issued a declaration dated October 3, 2018 saying that he had found no primary files pertaining to Rich (meaning the FBI didn’t investigate his death, DC did), and that on appeal of this September 1, 2017 FOIA, he had even searched for references to Rich, but found nothing.

Clevenger argued that that claim is inconsistent with the deposition of former AUSA Deborah Sines in one of the related Seth Rich lawsuits where she was asked about claims she made to Michael Isikoff and Andy Kroll. Specifically, Sines revealed that she was interviewed by a Mueller AUSA.

According to Ms. Sines’s testimony, the FBI conducted an investigation into possible hacking attempts on Seth Rich’s electronic accounts following his murder. Ms. Sines also testified that the FBI examined Seth Rich’s laptop computer as part of its investigation, and that there should be emails between her and FBI personnel. Finally, she testified that she met with a prosecutor and an FBI agent assigned to Special Counsel Robert Mueller.

Ms. Sines’s testimony conflicts with the affidavit testimony of David M. Hardy, who claimed that the FBI conducted a reasonable search and could not find any records pertaining to Seth Rich. See October 3, 2018 Affidavit of David M. Hardy (http://lawflog.com/wpcontent/uploads/2020/01/Hardy-Declaration.pdf) and July 29, 2019 Affidavit of David M. Hardy (http://lawflog.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Second-Hardy-Declaration.pdf). Mr. Hardy’s affidavits were also contradicted by email records that Judicial Watch obtained in Judicial Watch, Inc. v. U.S. Department of Justice, Case No. 1:18-cv-00154-RBW (D.D.C.). See August 10, 2016 email string (https://tinyurl.com/wylcu9l or http://lawflog.com/wpcontent/uploads/2020/04/FBI-emails-re-Seth-Rich.pdf). Clearly, the FBI is in possession of email records pertaining to Seth Rich.

Clevenger insists that records of this interview should have shown up in response to his September 1, 2017 FOIA.

Based on what the government released, it is true that Hardy’s declaration was wrong. There was an August 10, 2016 email chain via which a Washington Field Office press person alerted people to press questions after Julian Assange alleged Rich had a role in the email leak; the email chain ultimately included Peter Strzok. There was a September 1, 2016 notation by the San Francisco team that first investigated Guccifer 2.0 about something (probably information shared by either Twitter or WordPress). There were two copies of a 302 reporting on the September 14, 2016 interview of a DNC staffer (possibly Ali Chalupa) whose interview mentioned both Paul Manafort and Rich.

Those are the only things turned over, however, that pre-date Clevenger’s September 1, 2017 FOIA. So they’re the only things that Hardy should have found in his reference check.

That said, the claim that Hardy covered up details about Sines probably doesn’t hold up.

The document opening a case on a Dark Web threat, which may reflect the FBI investigation into allegations that someone tried to hack Rich’s email, is dated November 7, 2017.

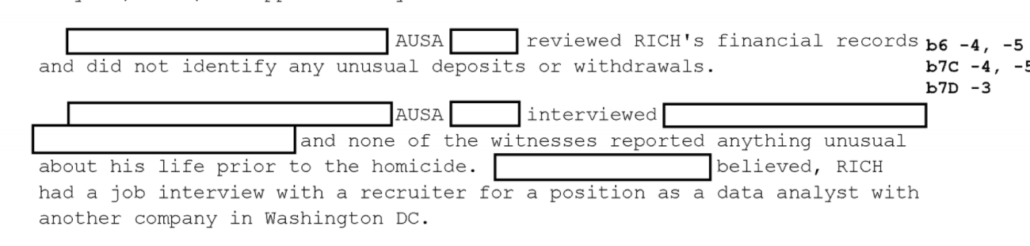

And what is almost certainly Sines’ interview with Mueller detailee Heather Alpino took place on March 15, 2018. In addition to the AUSA’s explanation that she (again, almost certainly Sines) had collected all the conspiracy theories floating about Rich’s death, the 302 also reveals that the AUSA reviewed Rich’s financial records and job prospects as part of the investigation.

The 302 is also consistent — as are multiple other documents from this release — with the FBI obtaining Rich’s laptop after Clevinger’s original FOIA, as part of the Mueller investigation. The 302 shows the AUSA “request[ing] a forensic image of the laptop for the homicide investigation” from Alpino. If that’s right, the FBI didn’t even get Rich’s laptop until months after Clevenger first FOIAed for such information. The FBI received voluntary production of something on October 24, 2017, some of which was too large to be uploaded digitally, which could be the laptop. The FBI also received information on May 30, 2018 from the DNC which must include material pertaining to Rich.

Again, all that post-dates the original FOIA, and so would not have been included in Hardy’s search.

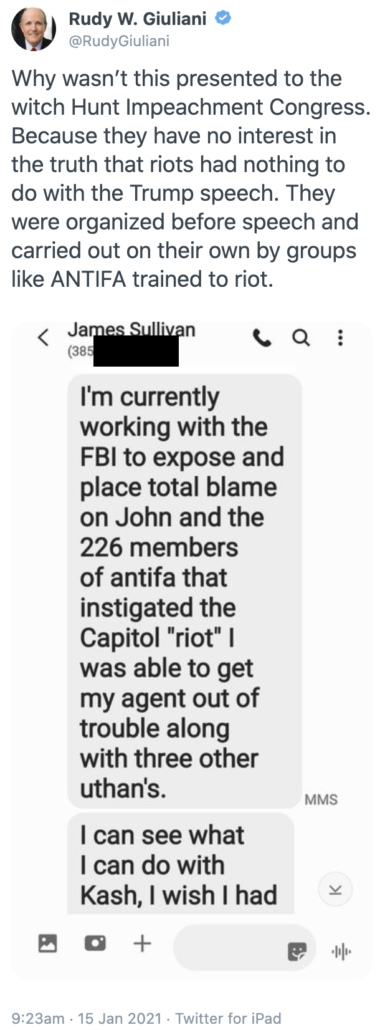

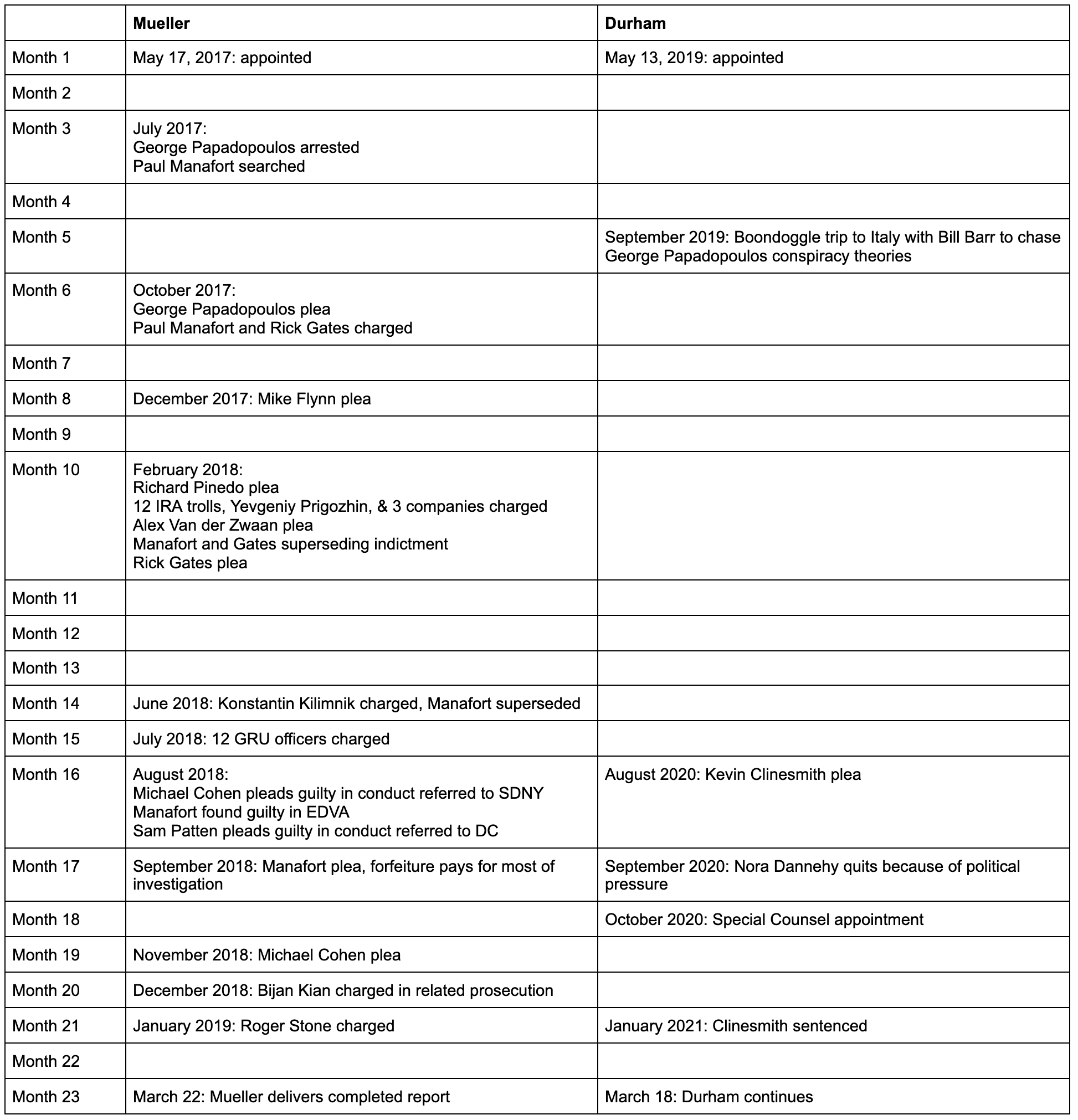

Indeed, these records indicate that the Mueller and hacking investigation did a lot of the things that the conspiracists claim they didn’t do, including chasing down the Seth Rich allegations, largely because the allegations floated by Roger Stone and Jerome Corsi became a focus of the investigation. The release includes two consent to search forms signed by Jerome Corsi on October 4, 2018, which suggest his electronic files were of interest in part because of claims he made about Seth Rich.

There are, however, a few interesting tidbits in here.

On April 9, 2019, the “SCO team” referred “information on a potential fraud scheme collected in the course of a Special Counsel’s Office.” That suggests one of the referrals Mueller made had to do with a fraud scheme involving Seth Rich.

A far more interesting document involves two pages of a 15-page 302 reflecting a 4-hour recorded interview that took place on October 2, 2019 between two FBI Agents and Dana Rohrabacher. Rohrabacher doesn’t appear to have had an attorney present. The interview covered “a wide variety of topics,” including people Rohrabacher had known going back to the Reagan administration. But the fragment pertaining to Rich appears among discussions about business relationships Rohrabacher had, including someone being asked to write articles of some sort (it’s not impossible that this is a reference to Corsi). The passage that probably relates to Rich is redacted for ongoing investigation. The circumstances under which alleged Russian asset Dana Rohrabacher would have a 4-hour recorded interview with the FBI are very curious indeed.

A word about what was included in this batch: The FBI put together a collection of 576 responsive pages that only provided pages that provided context to the reference to Rich, along with the page reference itself (so an entire 302 was only included if the entire interview pertained to Rich, otherwise they included the introductory page and the page with the Rich reference). Then, they withheld a bunch of pages in entirety, leaving fewer than 80 pages in the released files. So we don’t get to see every page (and a number of these files are Mueller files that were already released).

But what we do get to see reflect nothing of real interest that was in the FBI files when Clevenger first submitted his FOIA.

Update: This release includes some files (including the Sines one and a Jason Fishbein) that should have been turned over to BuzzFeed as part of that FOIA but I believe were not.

They also reprocessed this Jerome Corsi interview report, which doesn’t disclose anything that wasn’t already known, and this Paul Manafort interview report. The latter newly reveals that every day the week before the Podesta files dropped, Roger Stone told him they were coming, which makes it clear Stone didn’t have a lot of clarity on the timing of the release. It also shows Manafort recalling that, “Stone said things would come out related to Podesta. He did not recall that Stone specifically mentioned Podesta’s emails, just that Stone said it related to Podesta.” Similar Manafort testimony had shown up elsewhere, but this confirms that Manafort repeatedly testified that Stone knew the second WikiLeaks dump would pertain to Podesta.

Update: Corrected the timing of when FBI may have obtained Rich’s laptop.

Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0)