Thanks to those who’ve donated to help defray the costs of trial transcripts. Your generosity has funded the expected costs. If you appreciate the kind of coverage no one else is offering, we’re still happy to accept donations for this coverage — which reflects the culmination of eight months work.

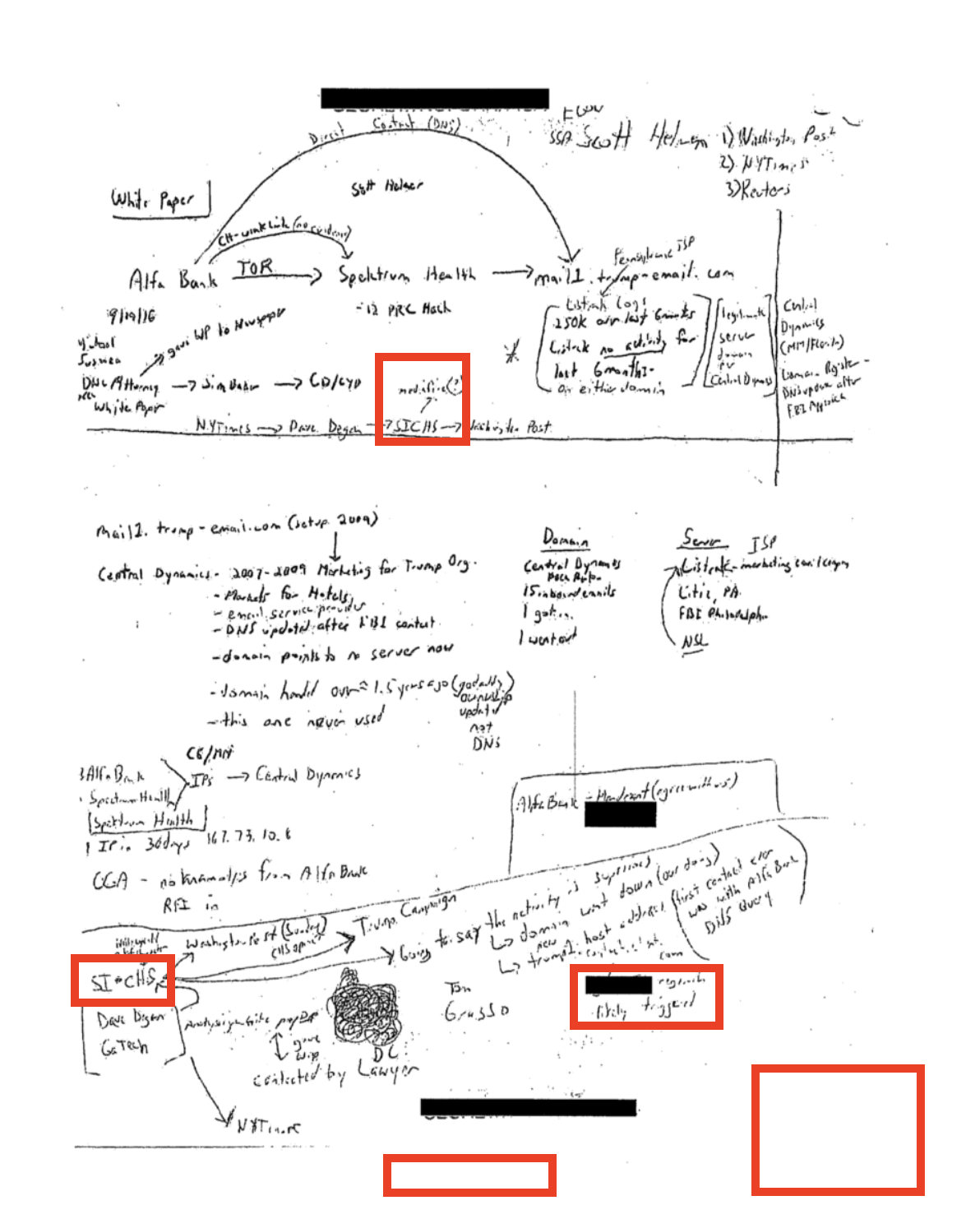

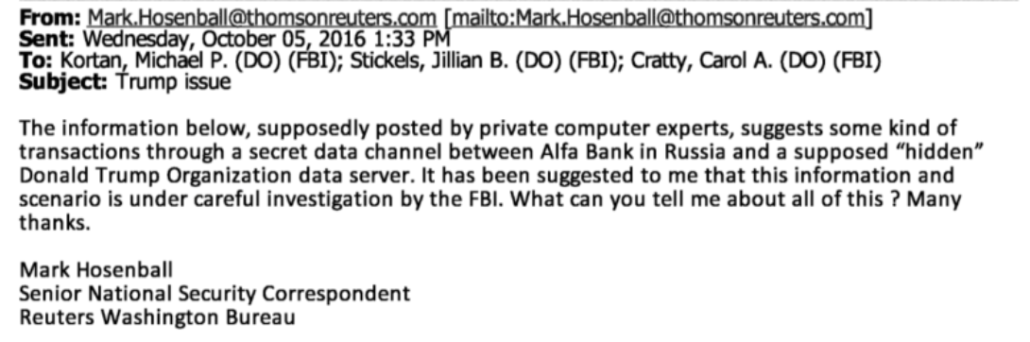

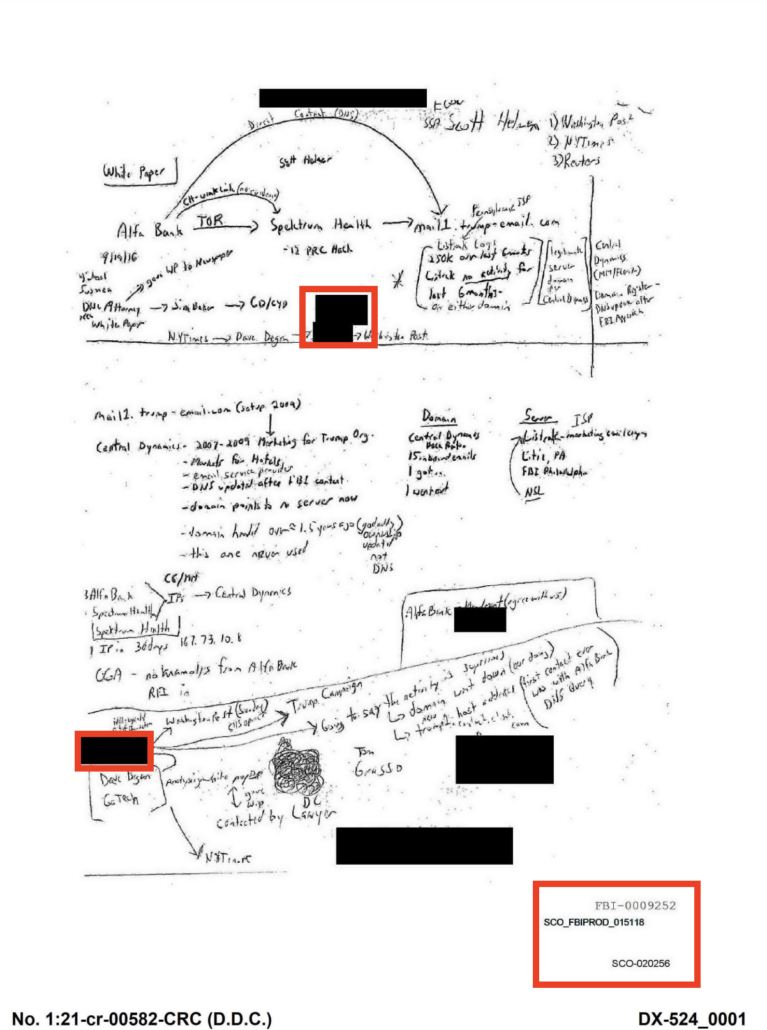

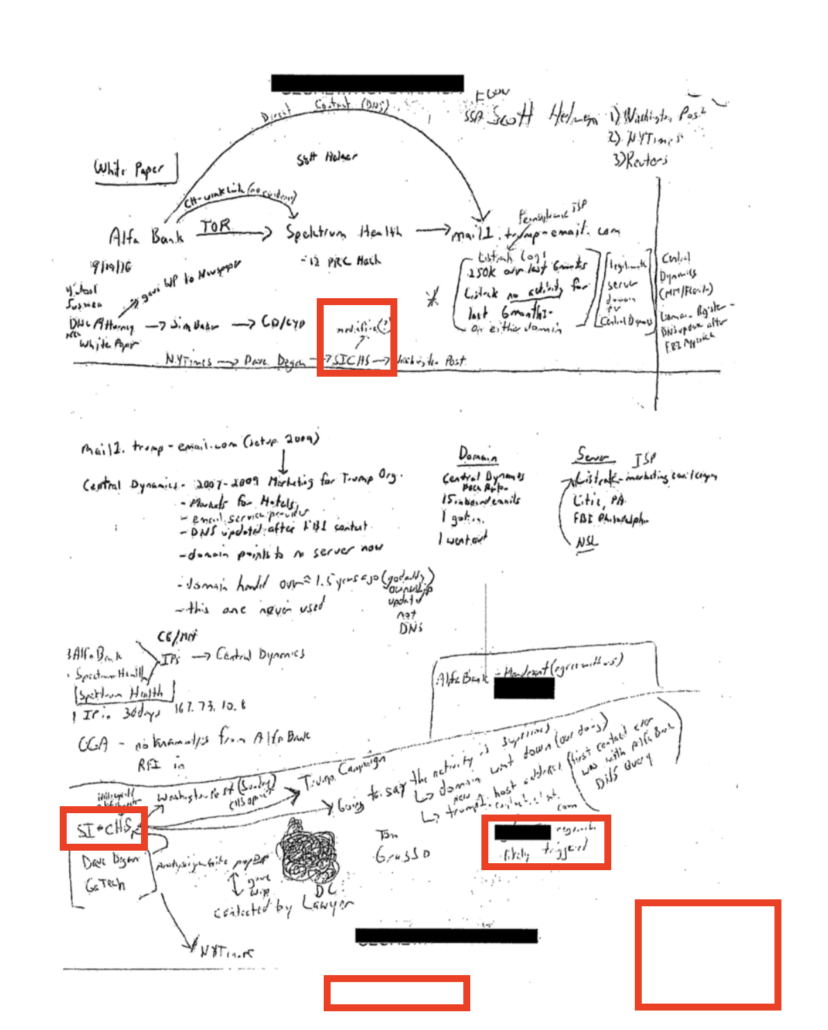

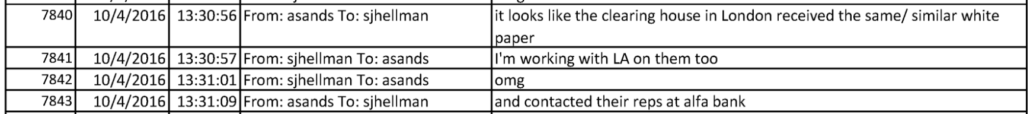

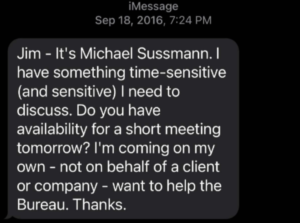

When Michael Sussmann attorney Sean Berkowitz was walking FBI Agent Scott Hellman through the six meetings he had with Durham’s team on Tuesday — meetings he first had as a witness about the investigation into the Alfa Bank allegations and later in preparation for his trial testimony — Berkowitz asked Hellman about how, sometime earlier this year, Andrew DeFilippis and Jonathan Algor asked him whether he could serve as their DNS expert for the trial.

Q And then, more recently, you met with Mr. DeFilippis and I think Johnny Algor, who is also at the table here, who’s an Assistant U.S. Attorney. Correct?

A. Yes.

Q. They wanted to talk to you about whether you might be able to act as an expert in this case about DNS data?

A. Correct.

To Hellman’s credit, he told Durham’s prosecutors — who have been investigating matters pertaining to DNS data for two years — that he only had superficial knowledge of DNS and so wasn’t qualified to be their expert.

Q. You said, while you had some superficial knowledge, you didn’t necessarily feel qualified to be an expert in this case, correct, on DNS data?

A. On DNS data, that’s correct.

It wasn’t until the third day of trial before Durham’s team presented any evidence about the alleged crime. Instead, Durham’s first two witnesses were their nominal expert, David Martin, and Hellman, who told Durham he wasn’t an expert but who offered opinions he neither had the expertise to offer nor had done the work to substantiate.

That’s important, because DeFilippis used him to provide an opinion only an expert should give. And virtually everything about his testimony — his claim to have relied on the data in the materials without looking at the thumb drives, an apparently made up claim about the timing of the analysis, and behaviors that the FBI normally finds suspicious — suggest he’s not only not a DNS expert qualified to assess this report, but his assessment of the white paper Sussmann shared also suffers from serious credibility issues.

The battle over an expert

The testimony of the nominal expert, David Martin, was remarkably nondescript, particularly given the fight that led up to his testimony. Durham’s team sprung even having an expert on Sussmann at a really late date: on March 30, after months of blowing off Sussmann’s inquiries if they would. Not only did they want Martin to explain to the jury what DNS and Tor are, Durham’s team explained, but they also wanted him to weigh in on the validity of conclusions drawn by researchers who had found the anomaly.

- the authenticity vel non of the purported data supporting the allegations provided to the FBI and Agency-2;

- the possibility that such purported data was fabricated, altered, manipulated, spoofed, or intentionally generated for the purpose of creating the false appearance of communications;

- whether the DNS data that the defendant provided to the FBI and Agency-2 supports the conclusion that a secret communications channel existed between and/or among the Trump Organization, Alfa Bank, and/or Spectrum Health;

[snip]

- the validity and plausibility of the other assertions and conclusions set forth in the various white papers that the defendant provided to the FBI and Agency-2;

As Sussmann noted in his motion to limit Martin’s testimony, he didn’t mind the testimony about DNS and Tor. He just didn’t want this trial to be about the accuracy of the data, especially without the lead time to prepare his own expert.

As the Government has already disclosed to the defense, should the defense attempt to elicit testimony surrounding the accuracy and/or reliability of the data that the defendant provided to the FBI and Agency-2, Special Agent Martin would explain the following:

- That while he cannot determine with certainty whether the data at issue was cherry-picked, manipulated, spoofed or authentic, the data was necessarily incomplete because it was a subset of all global DNS data;

- That the purported data provided by the defendant nevertheless did not support the conclusions set forth in the primary white paper which the defendant provided to the FBI;

- That numerous statements in the white paper were inaccurate and/or overstated; and

- That individuals familiar with these relevant subject areas, such as DNS data and TOR, would know that such statements lacked support and were inaccurate and/or overstated.

Based off repeated assurances from Durham that they weren’t going to make accuracy an issue in their case in chief, Judge Cooper ruled that the government could only get into accuracy questions if Sussmann tried to raise the accuracy of the data himself. But if he said he relied on the assurances of Rodney Joffe, it wouldn’t come in.

The government suggests that Special Agent Martin’s testimony may go further, depending on what theories Sussmann pursues in cross-examination or his defense case. Consistent with its findings above, the Court will allow the government’s expert to testify about the accuracy (or lack thereof) of the specific data provided to the FBI here only in certain limited circumstances. In particular, if Sussmann seeks to establish at trial that the data were accurate, and that there was in fact a communications channel between Alfa Bank and the Trump Campaign, expert testimony explaining why this could not be the case will become relevant. But, as the Court noted above, additional testimony about the accuracy of the data—expert or otherwise—will not be admissible just because Mr. Sussmann presents evidence that he “relied on Tech Executive-1’s conclusions” about the data, or “lacked a motive to conceal information about his clients.” Gov’s Expert Opp’n at 11. As the Court has already explained, complex, technical explanations about the data are only marginally probative of those defense theories. The Court will not risk confusing the jury and wasting time on a largely irrelevant or tangential issue. See United States v. Libby, 467 F. Supp. 2d 1, 15 (D.D.C. 2006) (excluding evidence under Rule 403 where “any possible minimal probative value that would be derived . . . is far outweighed by the waste of time and diversion of the jury’s attention away from the actual issues”).

Then, days before the trial, the issue came up again. Durham sent a letter on May 6 (ten days before jury selection), raising a bunch of new issues they wanted Martin to raise. Sussmann argued that Durham was trying to expand the scope of what his expert could present. Among his complaints, Sussmann argued that Durham was trying to make a materiality argument via his expert witness.

Third, the Special Counsel apparently intends to offer expert testimony about the materiality of the false statement alleged in this case. Indeed, the Special Counsel’s supplemental topic 9 regarding the importance of considering the collection source of DNS data is plainly being offered to prove materiality. But the Special Counsel did not disclose this topic in either his initial expert disclosure or Opposition, and the Court’s ruling did not permit such testimony. The Special Counsel should not now be allowed to offer an entirely new expert opinion under the guise of eliciting testimony regarding the types of conclusions that can be drawn from a review of DNS data.

Judge Cooper considered the issue Tuesday morning, before opening arguments. When asking why Martin had to present the concept of visibility, DeFilippis explained that Hellman–the Agent who’s not an expert on DNS but whom DeFilippis nevertheless had asked to serve as an expert on DNS–would talk about the import of knowing visibility to assess data.

THE COURT: Well, but isn’t the question here whether a case agent — is your case agent later going to testify that that was something that the FBI looked at or wanted to look at in this case and was unable to do so, and that that negatively affected the FBI’s investigation in some way? MR.

DeFILIPPIS: Yes, and I expect Special Agent Hellman, who will testify likely today, Your Honor, I expect that that is a concept that he will say was relevant to the determination that — determinations he was making as he drafted analysis of the data that came in. And, again, I don’t think we — for example, another way in which this comes up is that the FBI routinely receives DNS data from various private companies who collect that data, and it is always relevant sort of the breadth of visibility that those companies have. So it’s relevant generally, but also in this particular case the fact that the FBI did not have insight into the visibility or lack of visibility of that data certainly affected steps that the FBI took.

THE COURT: Okay. But Mr. Sussman has not been accused of misrepresenting who the source is. He’s simply — but rather who the client is. So how do you link that to the materiality of the alleged false statement?

MR. DeFILIPPIS: Because, Your Honor, I think we view them as intertwined. It was because — it was in part because Mr. Sussman said he didn’t have a client that made it more difficult for the FBI to get to the bottom of the source of this data or made it less likely they would, and so — and, again, I don’t think we expect to dwell for a long time on this, but I think the agents and the technical folks will say that that is part of why the origins of the data are extremely relevant when they took investigative steps here.

When Cooper noted Sussmann’s objection to Martin discussing possible spoofing of data, DeFilippis again answered not about what Martin would testify, but what Hellman would.

As DeFilippis explained, he claimed to believe that under Cooper’s ruling, the government could put in any little thing they wanted that they claimed had been part of the investigation.

And Special Agent Hellman, when he testifies today — now, Your Honor’s ruling we understand to permit us to put into evidence anything about what the FBI analyzed and concluded as its investigation unfolded because that goes to the materiality of the defendant’s statement. So Special Agent Hellman — through Agent Hellman we will offer into evidence a paper he prepared when the data first came in, and among its conclusions is that the data might — he doesn’t use the word “spoof” — but might have been intentionally generated and might have been fabricated. That was the FBI’s initial conclusion in what it wrote up.

So in order for the jury to understand the course of the FBI’s investigation and the conclusions that it drew at each stage, those concepts are at the center of it.

[snip]

MR. DeFILIPPIS: Okay. Your Honor, I’m sorry. We understood your ruling to be that the FBI’s conclusions as it went along were okay as long as we weren’t asserting the conclusion that it was, in fact, fabricated. You know, I mean, it’s difficult to chart the course of the FBI’s investigation unless we can elicit at each stage what it is that the FBI concluded.

Judge Cooper ordered that references to spoofing be removed — leading to a last minute redaction of an exhibit — but permitted a discussion of visibility to come in.

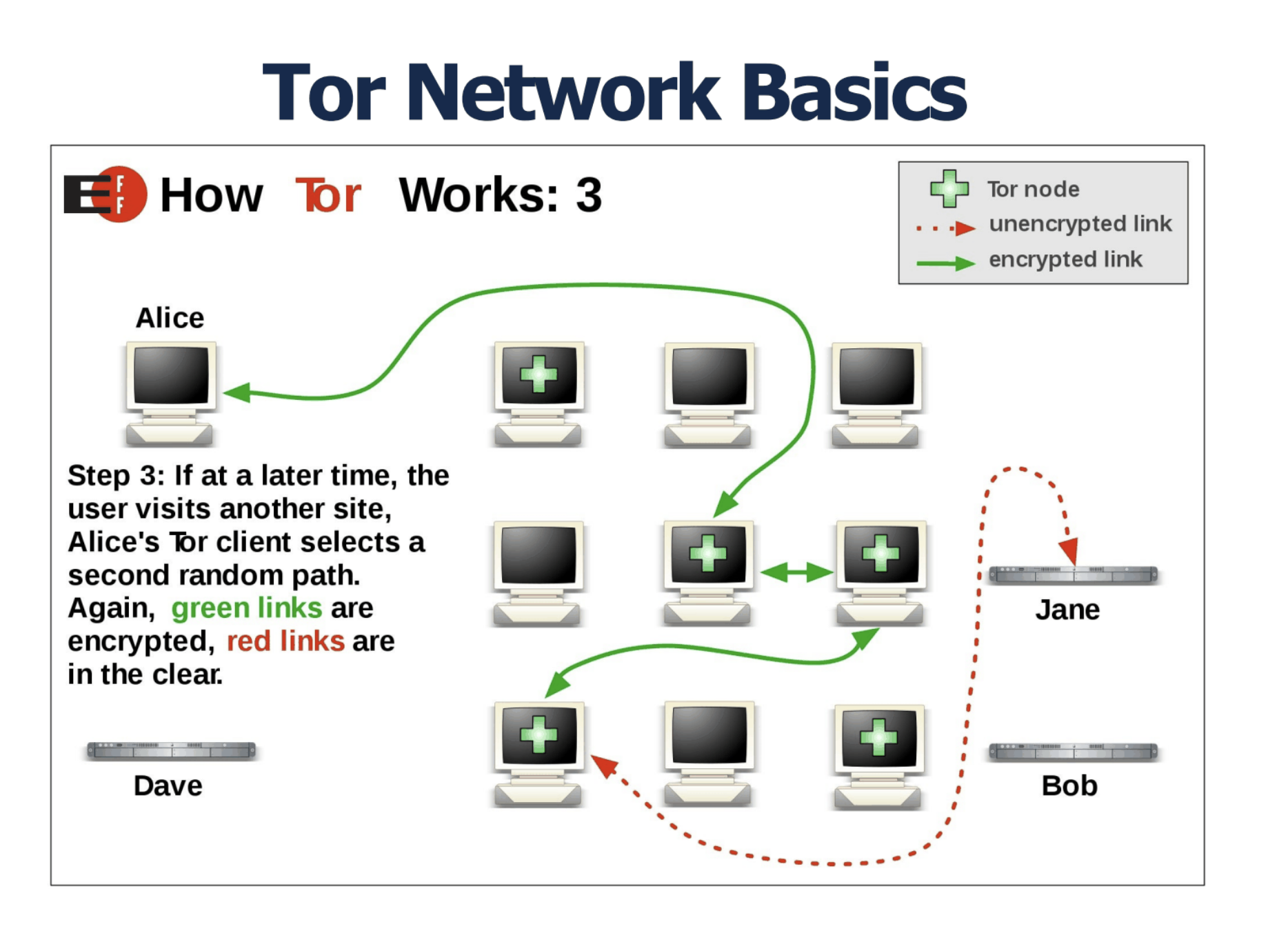

After all that fight, Martin’s testimony was not only bland, but it was recycled powerpoint. He not only admitted lifting the EFF description of Tor for his PowerPoint, but he included their logo.

Hellman delivers the non-expert expert opinion Durham was prohibited from giving

As I said, Martin was witness number one, Hellmann — the self-described non-expert in DNS — was witness number two.

Even though Hellman admitted, again, that he’s not a DNS expert, DeFilippis still had him go over what DNS is.

Q. How familiar or unfamiliar are you with what is known as DNS or Domain Name System data?

A. I know the basics about DNS.

Q. And in your understanding, on a very basic level, what is DNS?

A. DNS is basically how one computer would try and communicate with another computer.

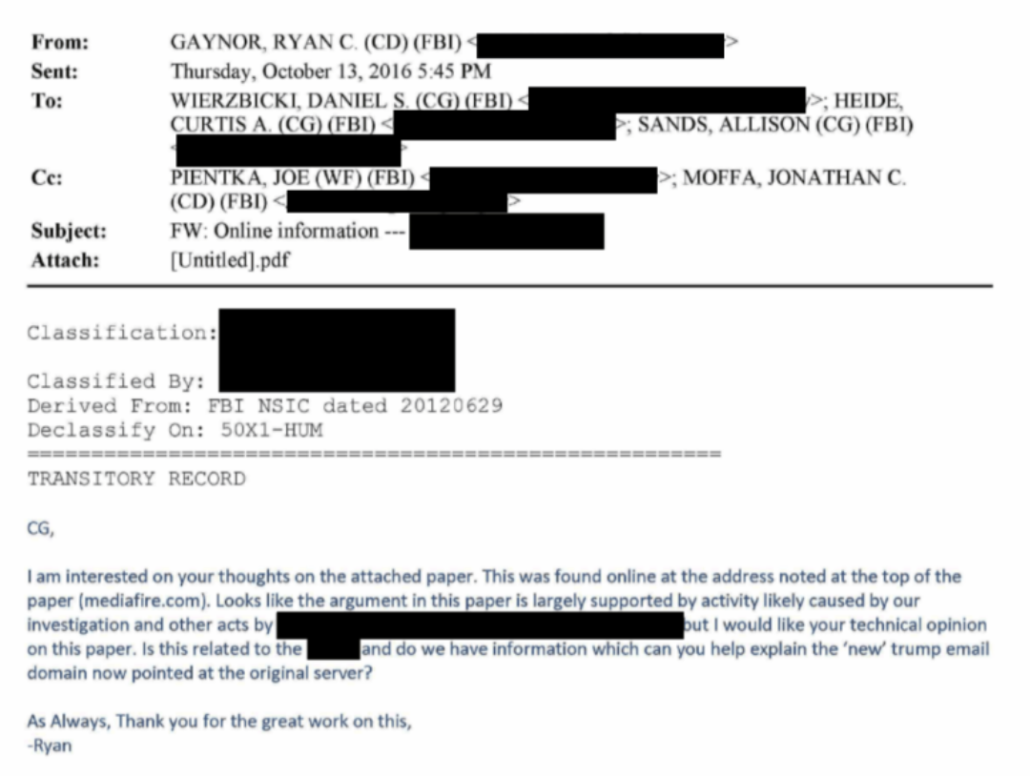

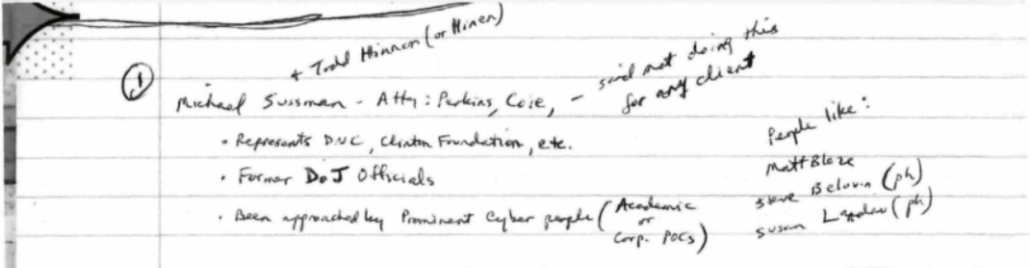

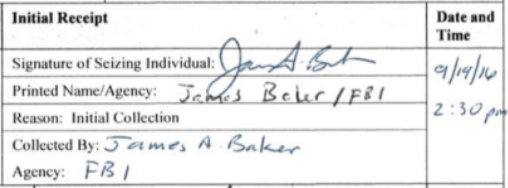

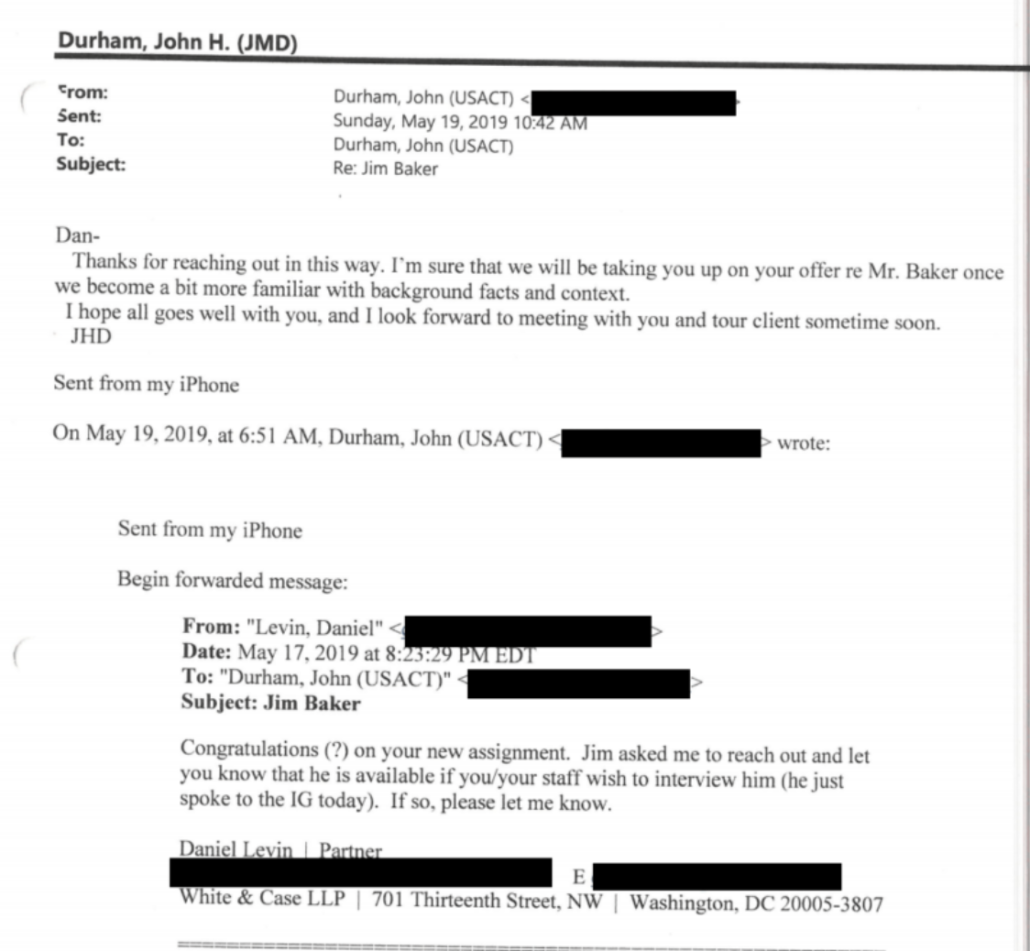

After getting Hellman to explain how he purportedly got chain of custody signatures on September 20, 2016 for the materials Michael Sussmann dropped off with James Baker on September 19, DeFilippis walked Hellman through how, he claimed, he had concluded that the allegations Sussmann dropped off were unsupported. Hellman reviewed the data accompanying the white paper, Durham’s star cybersecurity witness claimed on the stand, and after reviewing that data, determined there was no allegation of a hack in the materials and therefore nothing for the Cyber Division to look at. And, as a report he wrote “within a day” summarized, he concluded the methodology was horrible.

As you read the following exchange, know that (as I understand it) some, if not most, of what Hellman describes as the methodology is wrong. Obviously, if Hellman’s understanding of the methodology is wrong, then the opinion that DeFilippis elicits from a guy who admitted he was not an expert on DNS but whom DeFilippis nevertheless asked to serve as his expert witness on DNS before inviting David Martin in to present slides lifted from the Electronic Frontier Foundation instead [Takes a breath] … If Hellman’s understanding of the methodology and the data he’s looking at is wrong, then his opinion about the methodology is going to be of little merit.

With that understanding, note the objection of Sean Berkowitz, who fought DeFilippis’ late hour addition of an expert that DeFilippis wanted to use to opine on the validity of the research, bolded below.

So we looked at the top part, which set out your top-line conclusion. You then have a portion of the paper that says, “The investigators who conducted the research appear to have done the following.” Now, Special Agent Hellman, it appears to be a pretty technical discussion, but can you just tell us, in that first part of the paper, what did you set out and what did you conclude?

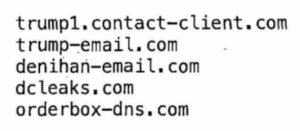

A. It looks to be that they were looking for domains associated with Trump, and the way that they did that was they looked at a list of sort of all domains and looked for domains that had the word “Trump” in them as a way to narrow down the number of domains they were looking at.

And then they wanted to find, well, which of that initial set of Trump domains, which of them are email servers associated with those domains. And the way they did that was to search for terms associated with email, like “mail” or other email-related terms to then narrow down their list of domains even further to be Trump-associated domains that were email servers.

Q. And did you opine on the soundness of that methodology? In other words, did you express a view as to whether this was a good way to go about this project?

A. We did not — I did not feel that that was the most expeditious way to go about identifying email servers associated with the domain.

Q. And why was that?

A. You can name an email server anything you want. It doesn’t have to have the words “mail” or “SMTP” in it. And so by — if you’re just searching for those terms, I would wager to guess you would miss an actual email server because there are other — there are other more technical ways that you can use — basically look-up tools, Internet look-up tools where you can say, for any domain, tell me the associated email server. That’s essentially like a registered email server. But the way that they were doing it was they were just looking for key terms, and I think that it just didn’t make sense to me why they would go about identifying email servers that way as opposed to just being able to look them up.

Q. Was there anything else about the methodology used here by the writer or writers of this paper that you found questionable or that you didn’t agree with?

A. I think just the overall assumptions that were being made about that the server itself was actually communicating at all. That was probably one of the biggest ones.

Q. And what, if anything, did you conclude about whether you believed the authors of the paper or author of the paper was fairly and neutrally conducting an analysis? Did you have an opinion either way?

MR. BERKOWITZ: Objection, Your Honor.

THE COURT: Basis?

MR. BERKOWITZ: Objection on foundation. He asked him his opinion. He’s not qualified as an expert for that.

THE COURT: I’ll overrule it.

A. Sorry, can you please repeat the question?

Q. Sure. Did you draw a conclusion one way or the other as to whether the authors of this paper seemed to be applying a sound methodology or whether, to the contrary, they were trying to reach a particular result? Did you —

A. Based upon the conclusions they drew and the assumptions that they made, I did not feel like they were objective in the conclusions that they came to.

Q. And any particular reasons or support for that?

A. Just the assumption you would have to make was so far reaching, it didn’t — it just didn’t make any sense.

That’s how, as his second witness, Andrew DeFilippis introduced the opinion of a guy who admitted he wasn’t an expert on DNS that DeFilippis had asked to serve as an expert even though DeFilippis should have known that he didn’t have the expertise to offer expert opinions like this.

If Sussmann is found guilty, I would bet a great deal of money this stunt will be one part of a several pronged appeal, because Judge Cooper permitted DeFilippis to do precisely what Cooper had prohibited him from doing before trial, and he let him do it with a guy who by his own admission is not a DNS expert.

Cyber Division reaches a conclusion without looking at the thumb drives

Now let’s look at what Hellman describes his own methodology to be.

First, it was quick. DeFilippis seems to think that serves his narrative, as if this stuff was so crappy that it took a mere glimpse to discredit it.

Q. Special Agent Hellman, how long would you say it took you and Special Agent Batty to write this up?

A. Inside of a day.

Q. Inside of a day, you said?

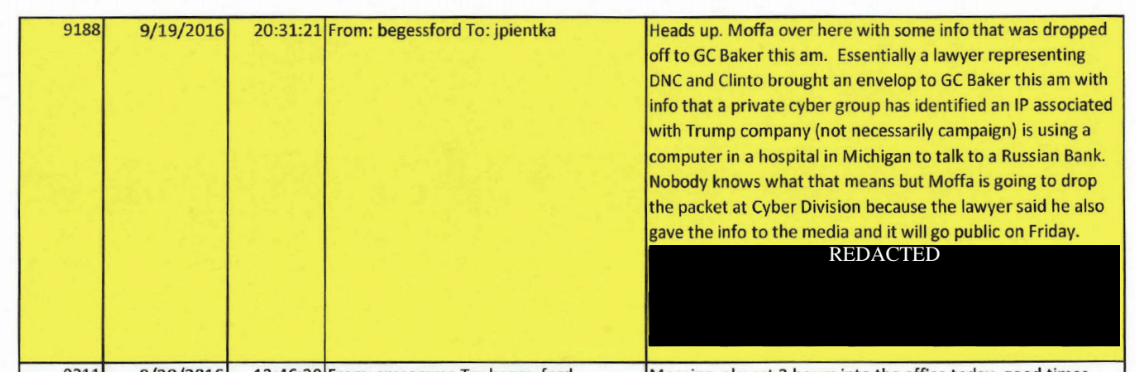

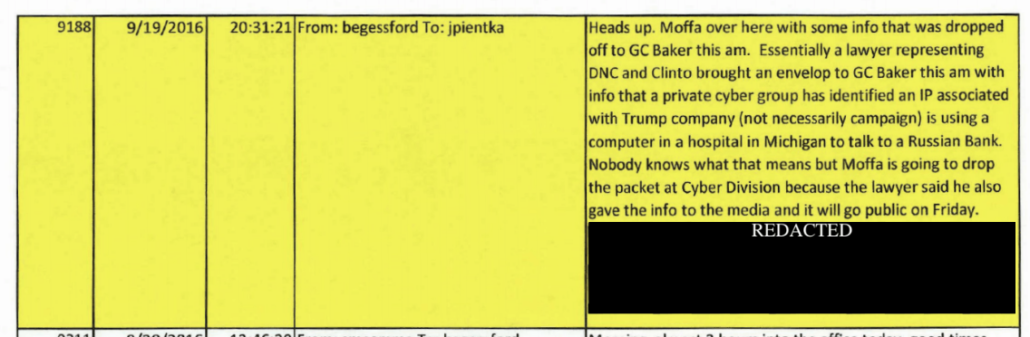

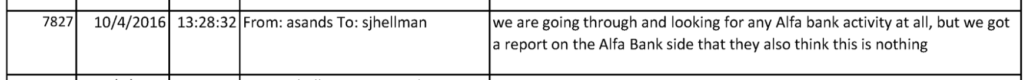

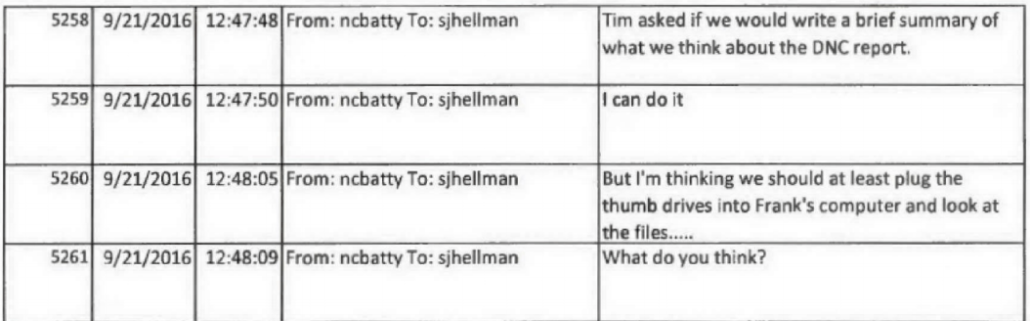

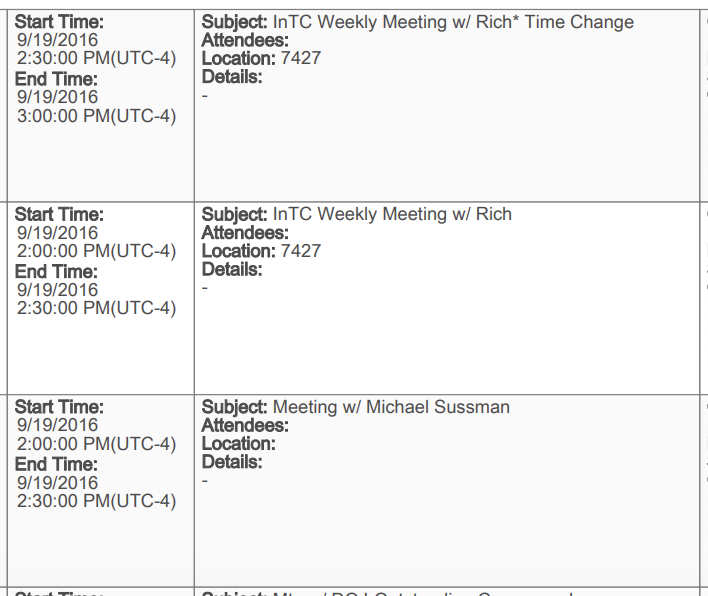

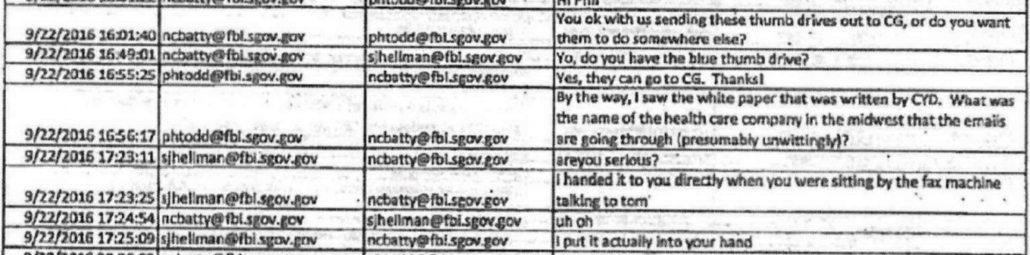

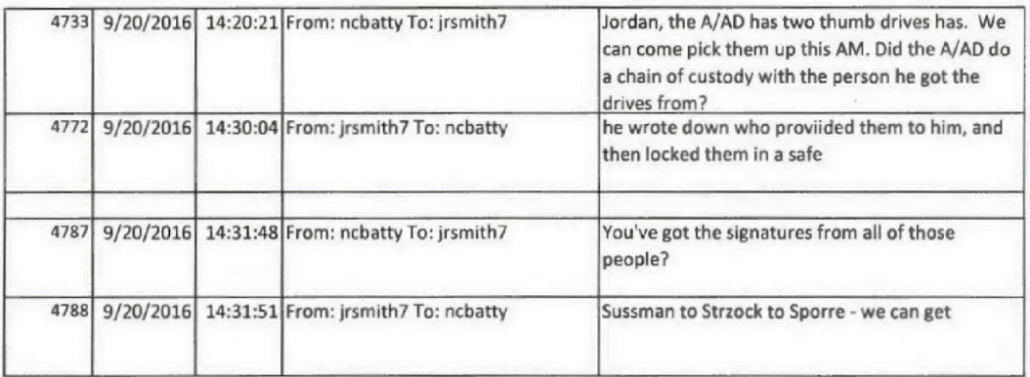

Berkowitz walked Hellman through the timeline of it, and boy was it quick. There’s some uncertainty about this timeline, because John Durham’s office doesn’t feel the need to make clear whether exhibits they’re turning over in discovery reflect UTC or ET. But I think I’ve laid it out below (Berkowitz got it wrong in cross-examination, which DeFilippis used to attack his analysis).

As you can see, not only were FBI’s crack cybersecurity agents making a final conclusion about the data within a day but — by all appearances — they did so before they had ever looked at the thumb drives included with the white papers. From the record, it’s actually not clear when — if!!! — they looked at the thumb drives. But it’s certain they had their analysis finalized no more than one working day after they admitted they hadn’t looked at the thumb drive, which was itself after they had already decided the white paper was shit.

Timeline

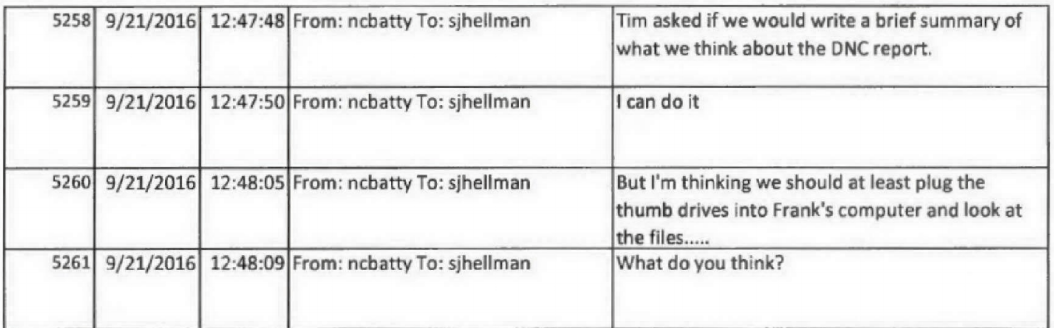

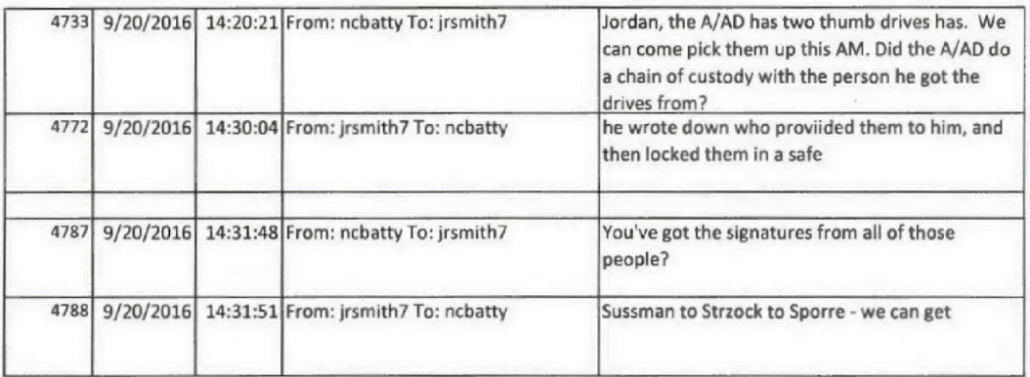

September 20, 10:20AM: Nate Batty tells Jordan Kelly they’ll come from Chantilly to DC get the thumb drives

September 20, 10:31AM: Jordan Kelly tells Batty the chain of custody is “Sussman to Strzock to Sporre”

September 20, 12:29PM: Hellman and Nate Batty accept custody of the thumb drives

September 20, 1:30PM: Hour drive back to Chantilly, VA

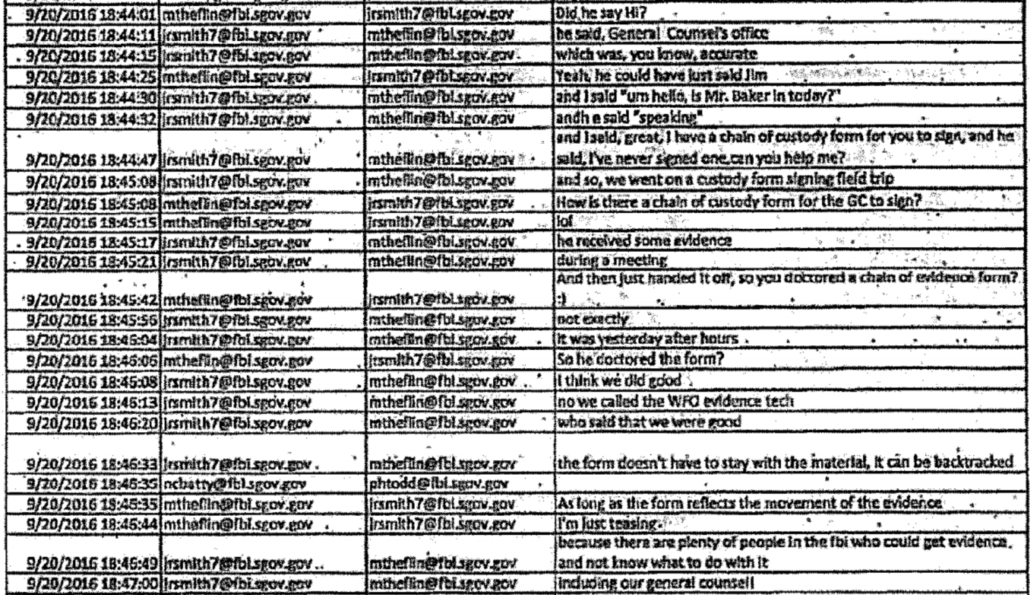

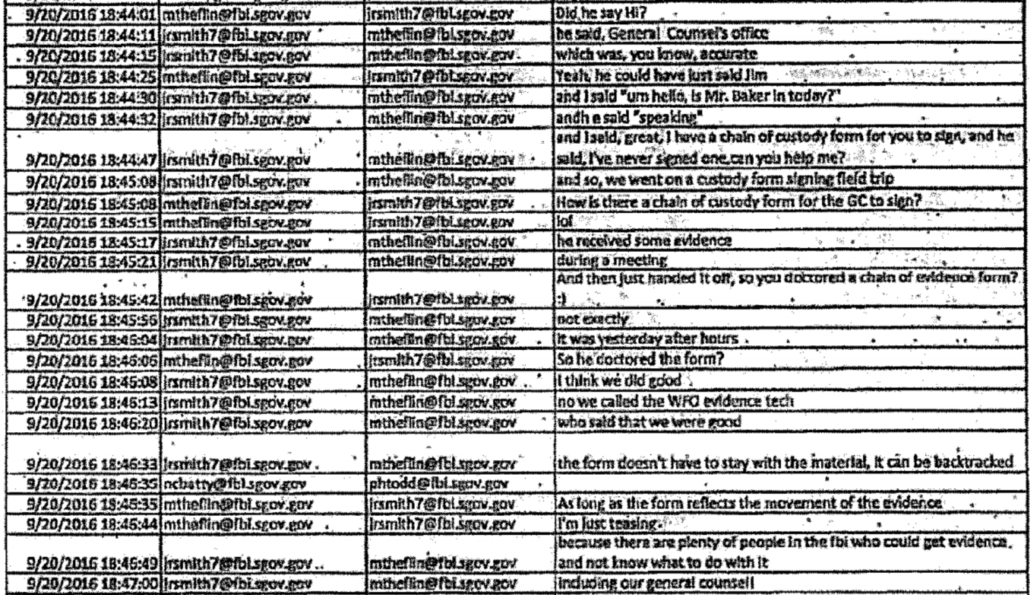

September 20, 4:44PM: Hellman appears to explain the process of picking up the thumb drives to jrsmith, claiming to have spoken to Baker on the phone. jrsmith jokes about “doctor[ing] a chain of evidence form.”

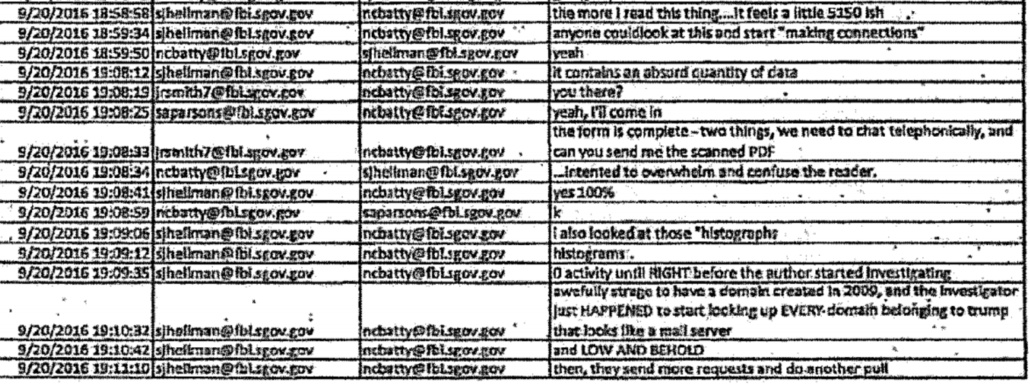

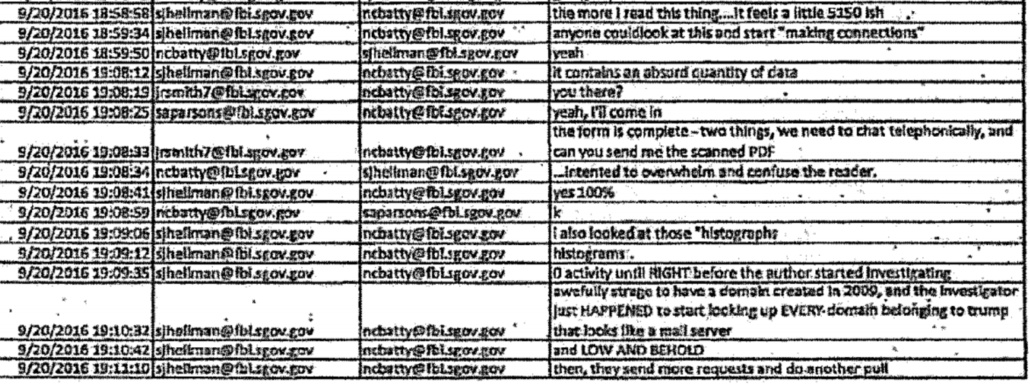

September 20, 4:58: Hellman says the more he reads the report “it feels a little 5150ish,” suggesting (as he explained to Berkowitz on cross) the authors suffered from a mental disability, and Hellman complains that “it contains an absurd quantity of data” to which Batty responded, the data seemed “inserted to overwhelm and confuse the reader.”

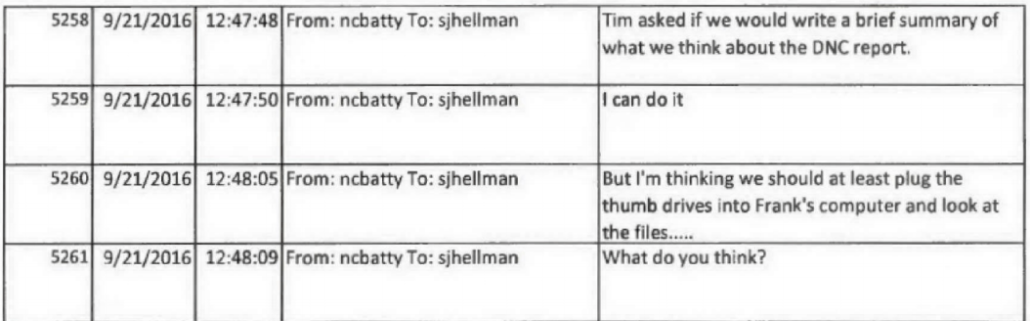

September 21, 8:47AM: Batty tells Hellman their supervisor wants them to “write a brief summary of what we think about the DNC report.” Batty continues by suggesting that “we should at least plug the thumb drives into Frank’s computer and look at the files…”

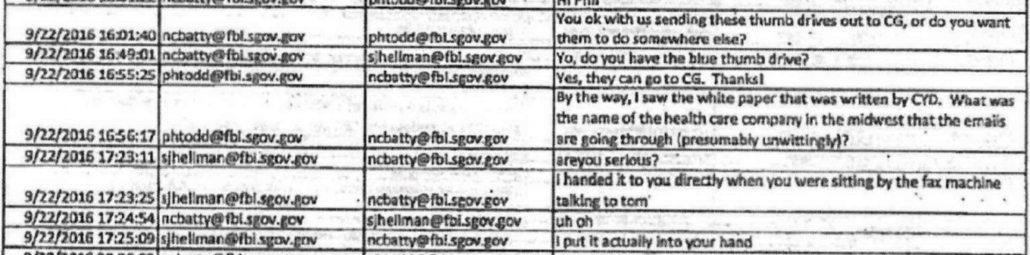

9/22, 9:44AM: Curtis Heide, in Chicago, asks Batty to send the contents of the thumb drive so counterintelligence agents can begin to look at the evidence. The boys in Cyber struggle to do so for a bit.

9/22, 2:49PM: Batty asks Hellman what he did with the blue thumb drive.

9/22, 4:46PM: Batty sends “analysis of Trump white paper” to others.

In other words, the cyber division spent less than 28 hours doing this analysis.

Yes. The analysis was quick.

Hellman says his analysis is valid because he looked at the data

The hastiness of the analysis and the fact that Hellman didn’t look at the thumb drive before making initial conclusions about the research is fairly problematic, because when he discussed his own methodology, he described the data driving everything.

Q. Now, what principally, from the materials, did you rely on to do your analysis?

A. So it was really two things. It was looking at the data, the technical data itself. There was a summary that it came with. And then also we were comparing what we saw in the data, sort of the story that the data told us, and then looking at the narrative that it came with and comparing our assessment of the data to the narrative.

[snip]

Q. And in connection with that analysis, did you also take a look at the data itself that was underlying this paper?

A. Yes

[snip]

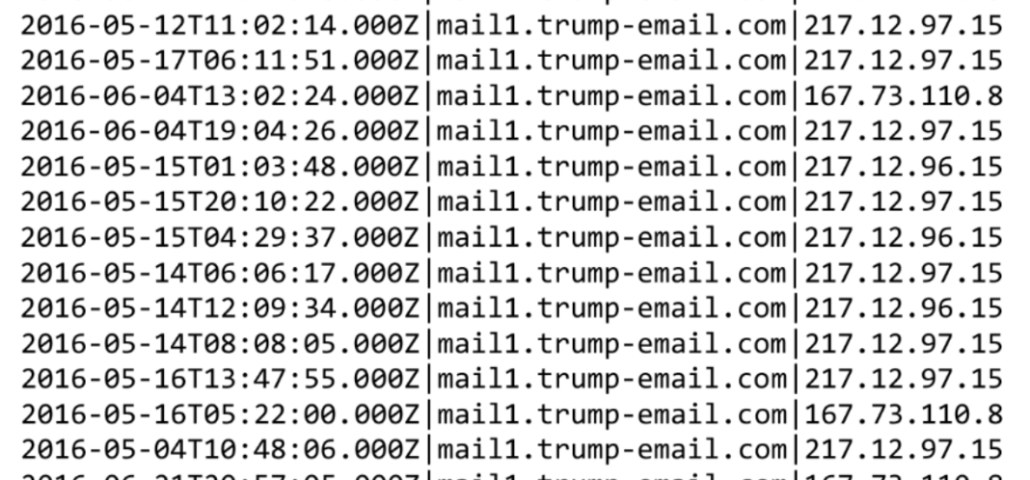

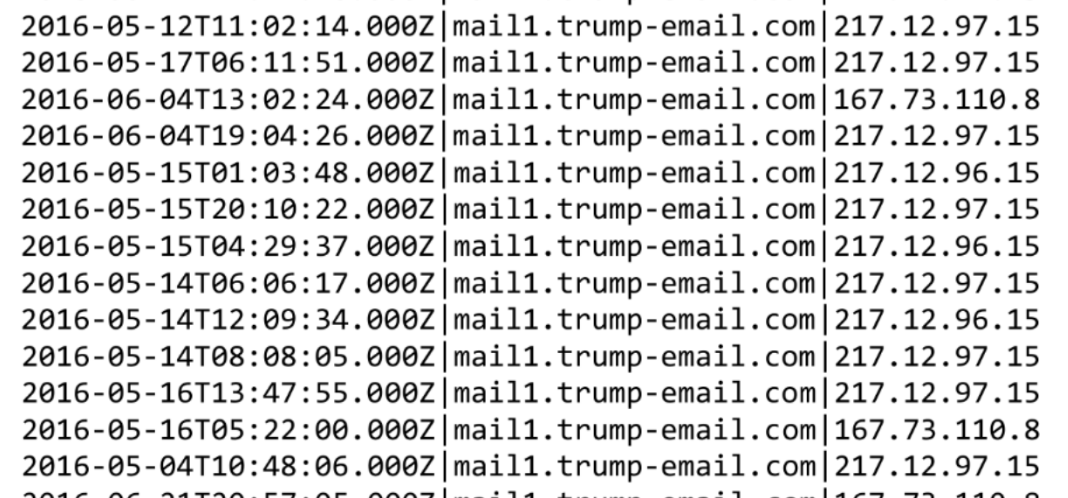

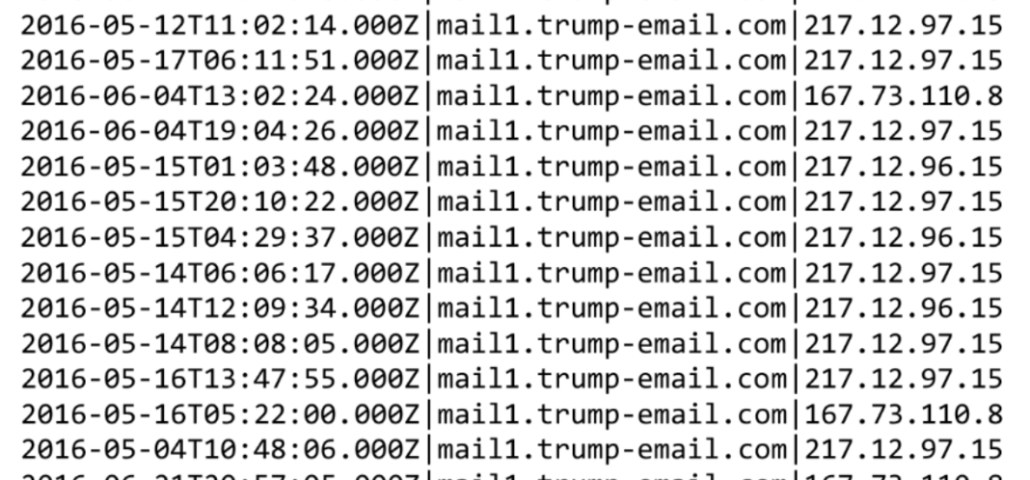

Q. And if we look at that first page there, Agent Hellman, what kind of data is this?

A. It appears to be — as far as I can tell, it looks to be — it’s log data. So it’s a log that shows a date and a time, a domain, and an IP address. And, I mean, that’s — just looking at this log, there’s not too much more from that.

Q. And do you understand this to be at least a part of the DNS data that was contained on the thumb drives that I think you testified about earlier?

A. Yes.

[snip]

A. It would have mattered — well, I think on one hand it would not have mattered from the technical standpoint. If I’m looking at technical data, the data’s going to tell me whatever story the data’s going to tell me independent of where it comes from. So I still would have done the same technical analysis.

But knowing where the data comes from helps to tell me — it gives me context regarding how much I believe in the data, how authentic it is, do I believe it’s real, and do I trust it. [my emphasis]

He repeated this claim on cross with Berkowitz.

I just disagreed with the conclusions they came to and the analysis that they did based upon the data that came along with the white paper.

When Berkowitz asked him why counterintelligence opened an investigation when Cyber didn’t, Hellman suggested that the people in CD wouldn’t understand how to read the technical logs.

A. Um, I think they’d probably be looking at it from the same vantage point, but if you’re not — you don’t have experience looking at technical logs, you may not have the capability of doing a review of those logs. You might rely on somebody else to do it. And perhaps counterintelligence agents are going to be thinking about other investigative questions. So I guess it would probably be a combination of both.

“If I’m looking at technical data,” DeFilippis’ star cybersecurity agent explained, “the data’s going to tell me whatever story the data’s going to tell me.”

Except he didn’t look at the technical data, at least not the data on the thumb drives, before he reached his initial conclusion.

Hellman makes a claim unsupported by the data in his own analysis

I’ll leave it to people more expert than me to rip apart Hellman’s own analysis of the white paper Sussmann shared with the FBI. In early consultations, I’ve been told he misunderstood the methodology, misunderstood how researchers used Trump’s other domains to prove that just one had this anomaly (that is, as a way to test their hypothesis), and misstated the necessity of some long-term feedback loop for this anomaly to be sustained. Again, the experts will eventually explain the problems.

One part of his report that I know damns his methodology, however, is where he says the researchers,

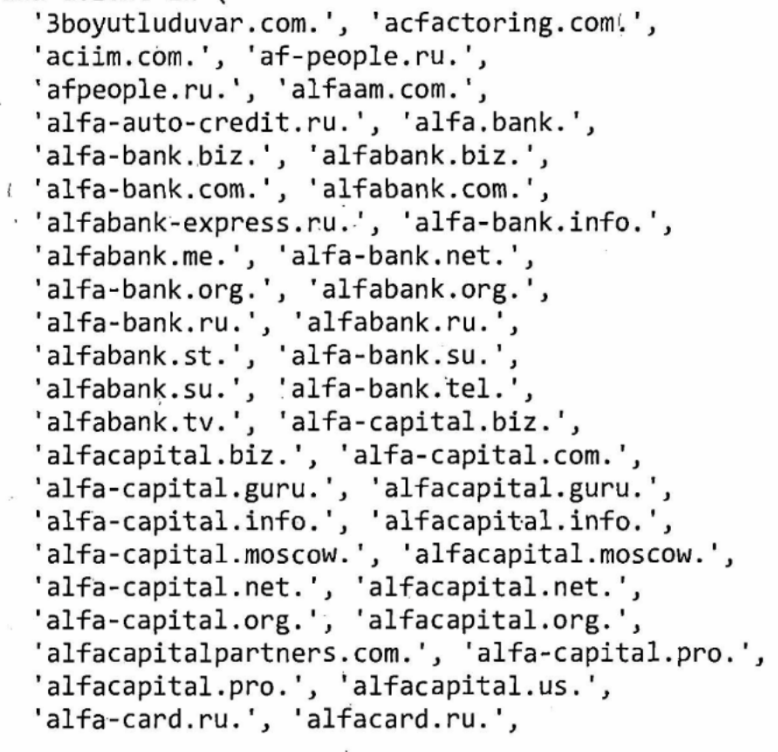

Searched “…global nonpublic DNS activity…” (unclear how this was done) and discovered there are (4) primary IP addresses that have resolved to the name “mail1.trump-email.com”. Two of these belong to DNS servers at Russian Alfa Bank. [my emphasis]

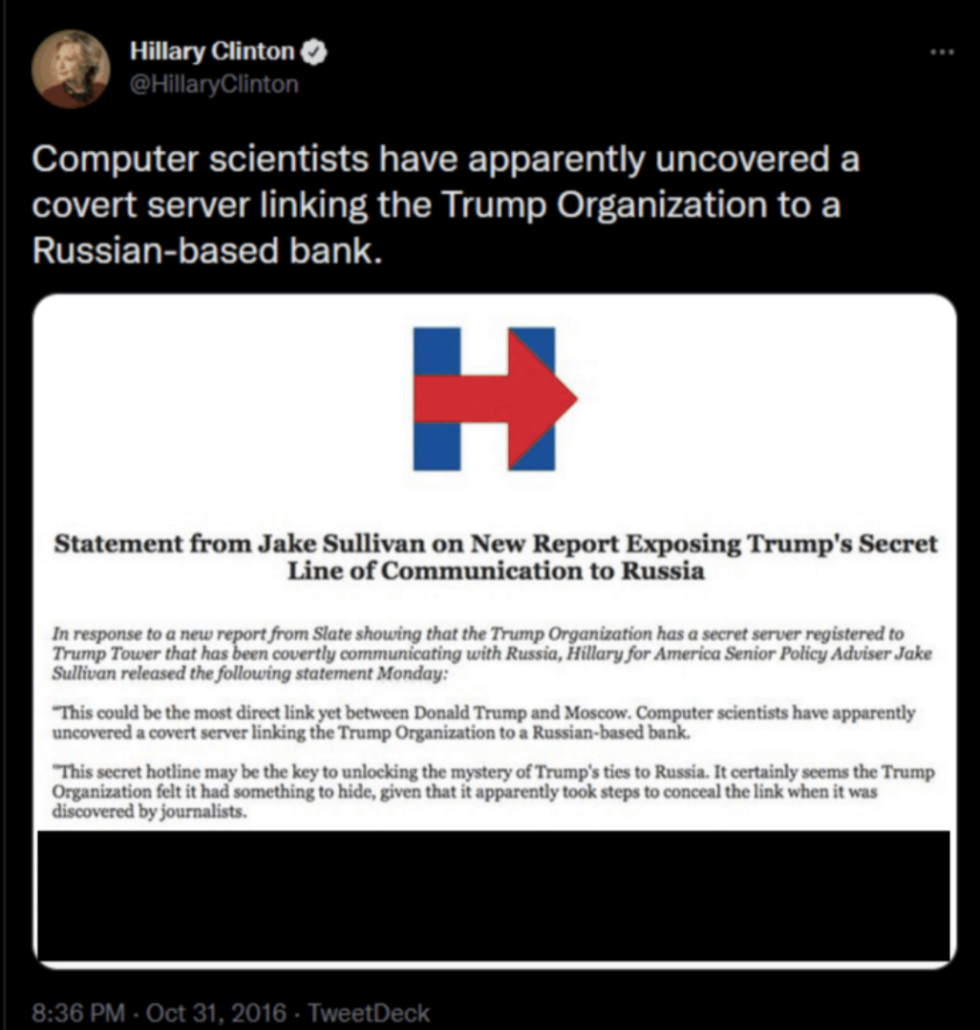

This is the point where every single person I know who assessed these allegations who is at least marginally expert on DNS issues stopped and said, “global nonpublic DNS activity? There are only a handful of people that could be!” See, for example, this Robert Graham post written in response to the original Slate story, perhaps the most influential critique of the allegations, probably even on Durham. Every marginally expert person I know has, upon reading something like that, tried to figure out who would have that kind of visibility on the data, because that kind of visibility, by itself, would speak to their expertise. Those marginally expert people did not have the means to identify the possible sources of the data. But a lot of them — including the NYTimes!! — were able to find people who had that kind of visibility to better understand the anomaly. When Hellman read that, he simply said, “unclear how this was done” and moved on.

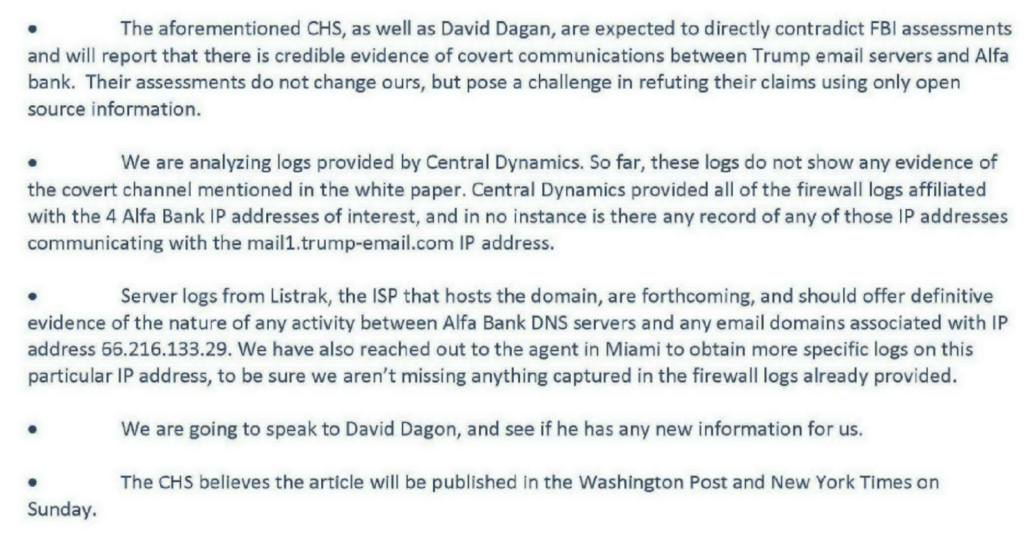

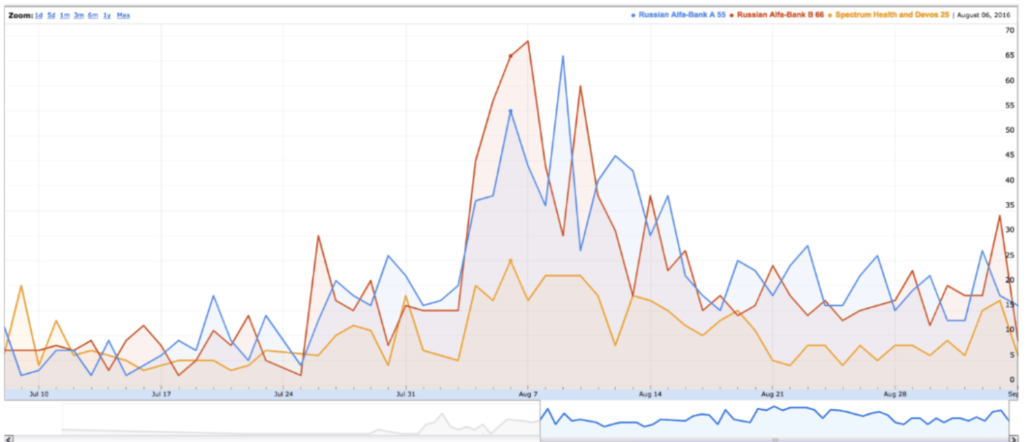

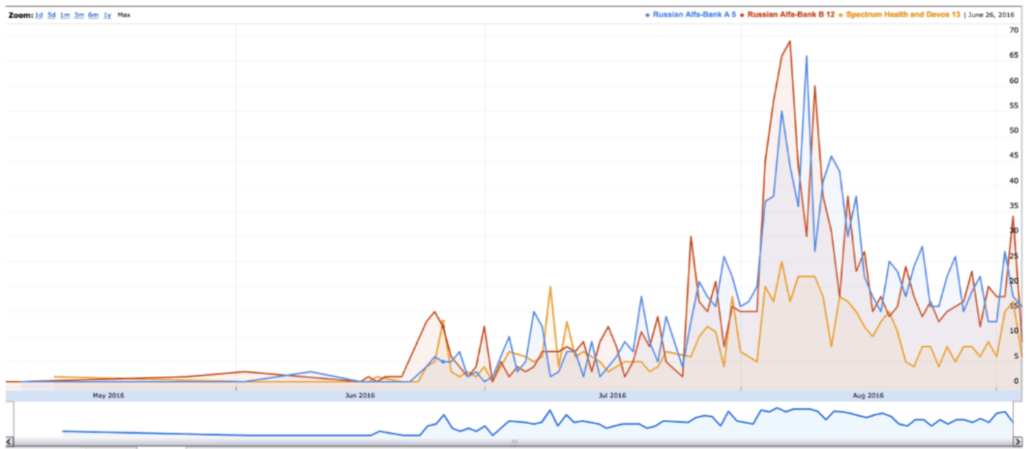

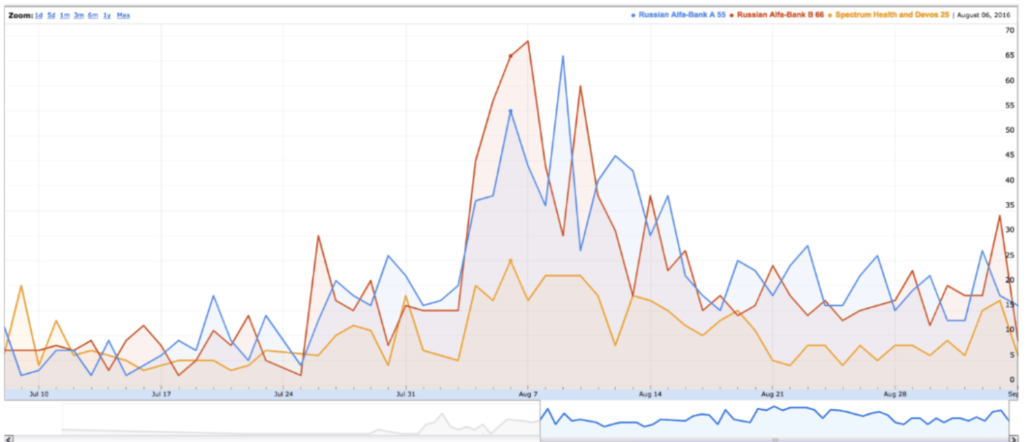

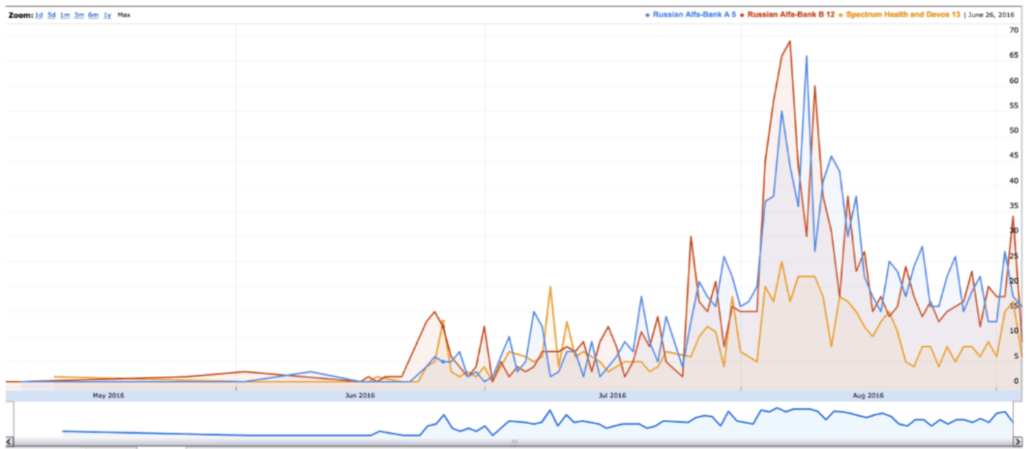

Still, Hellman did not contest (or possibly even test) the analysis that said there were really just four IP addresses conducting look-ups with the Trump marketing server. Dozens of people have continued to test that result in the years since, and while there have been adjustments to the general result, no one has disproven that the anomaly was strongest between Alfa Bank and Trump’s marketing domain.

Where Hellman’s insta-analysis really goes off the rails, however, is in his assertion that, “it appears that the presumed suspicious activity began approximately three weeks prior to the stated start date of the investigation conducted by the researcher.”

I’m not a DNS expert, but I’m pretty good at timelines, and by my read here are the key dates in the white paper.

May 4, 2016: Beginning date for look-up analysis

July 28, 2016: Lookup for hostnames yielding Trump

September 4, 2016: End date for look-up analysis

September 14, 2016: Updated search for look-ups covering June 17 through September 14

The start date reflected in this white paper is July 28, 2016. Three weeks before that would be July 7, 2016, a date that doesn’t appear in the white paper. The anomaly started 85 days before the start date reflected in this white paper (and the start date for the research began months earlier, but still over three weeks after the May 4 start date).

I don’t understand where he got that claim. But DeFilippis repeated it on the stand, as if it were reflected in the data, I guess believing it makes his star cybersecurity agent look good.

DeFilippis’ star cybersecurity agent has some credibility problems

There are a few more problems with the credibility of Hellman, DeFilippis’ star cybersecurity agent who is not a DNS expert. One of those is that he compared notes with his boss before first testifying.

Q: And you also spoke with Nate Batty around that time, Right?

A: Yes.

Q: Did you talk to him before the first interview to kind of get ready for it?

A: I think so, but I don’t remember.

Q: Is that something that you encourage witnesses to do, to talk to other witnesses to see if your recollections are consistent?

A: No.

In addition, notwithstanding that Batty was told that Sussmann was in the chain of control, Batty claimed to believe the source was “anonymous” and Hellmann claimed to believe it was sensitive–a human source. Even after comparing notes their stories didn’t match.

There are other problems with Hellman’s memory of the events, notably that in his first interview — the one he did shortly after comparing notes with Batty — he claimed that Baker had told him he was unable to identify the source of the data.

Q. And when you went to Mr. Baker’s office, do you remember what, if anything, was said during that discussion or during that interaction?

A. I remember being in the office, but I don’t distinctly recall what the conversation was. I do remember after the fact, though, that I was frustrated that I was not able to identify who had provided these thumb drives, this information to Mr. Baker. He was not willing to tell me.

At the very least, this presents a conflict with Baker’s testimony, but it’s also another testament to how variable memories can be four years, much less six years, after the fact.

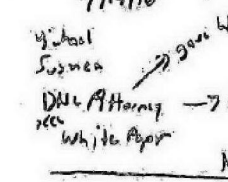

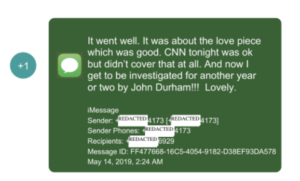

Hellman also claimed, when asked on cross, that the first time he had ever seen the reference to a “DNC report” in September 21 Lync notes he received was two years ago, when he was first interviewed.

A: The first time I saw this was two years ago when I was being interviewed by Mr. DeFilippis, and I don’t recall ever seeing it. I never had any recollection of this information coming from DNC. I don’t remember DNC being a part of anything we read or discussed.

Q: Okay. When you say, the first time you saw it was two years ago when you met with Mr. DeFilippis, that’s not accurate. Right? You saw it on September 21st, 2016. Correct?

A: It’s in there. I don’t have any memory of seeing it.

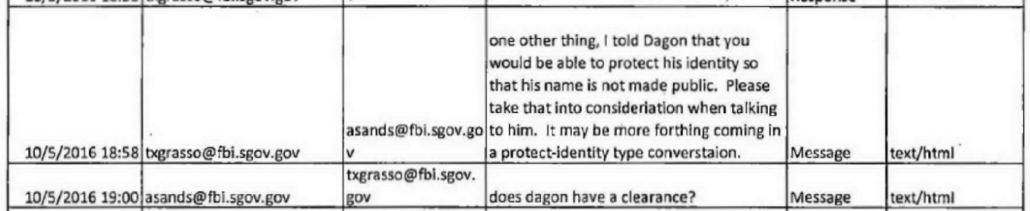

And when Sean Berkowitz asked about Hellman the significance of seeing the reference to a “DNC report” first thing on September 21, he described that DeFilippis suggested to him that it was likely just a typo for DNS.

Q. What’s your explanation for it?

A. I have no recollection of seeing that link message. And there is — I have absolutely no belief that either me or Agent Batty knew where that data was coming from, let alone that it was coming from DNC. The only explanation that popped or was discussed was that it could have been a typo and somebody was trying to refer to DNS instead of DNC.

Q. So you think it was a typo?

A. I don’t know.

Q. When you said the only one suggesting it — isn’t it true that it was Mr. DeFilippis that suggested to you that it might have been a typo recently?

A. That’s correct.

When asked about a topic for which there was documentary evidence Hellman had seen in real time that he claimed not to remember, Andrew DeFilippis offered up an explanation that Hellman then offered on the stand.

On the stand, DeFilippis also tried to get Hellman to call a marketing server a spam server, though Hellman resisted.

Once you look closely, I don’t think Hellman’s testimony helps Durham all that much. What it proves, however, is that DeFilippis attempted to coach testimony.

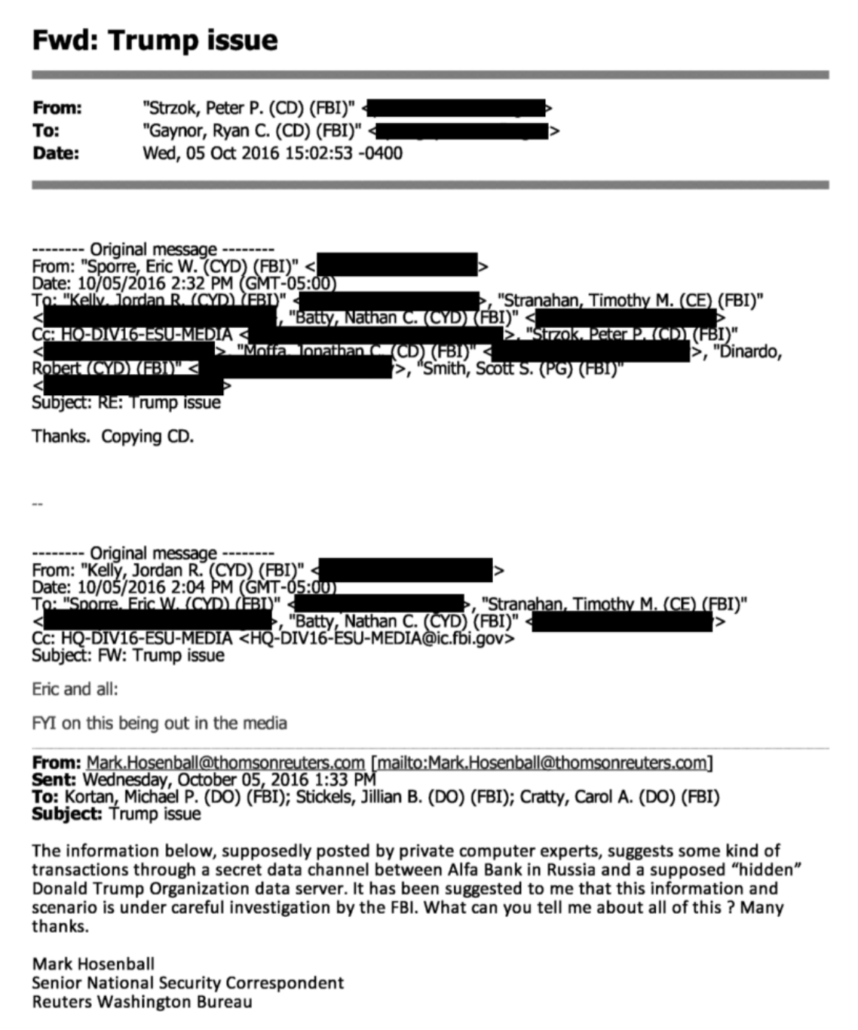

One final thing. DeFilippis got his star cybersecurity agent to observe that the researchers didn’t include their name or other markers on their report, as if that’s a measure of unreliablity.

Q. Now, let me ask you, were you able to determine from any of these materials who had actually drafted the paper alleging the secret channel?

A. No.

Q. In other words, was it contained anywhere in the documents?

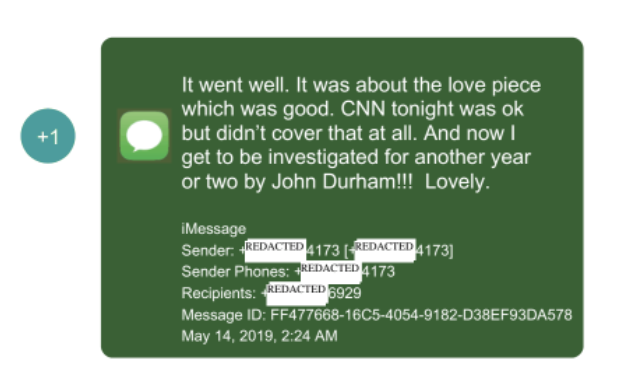

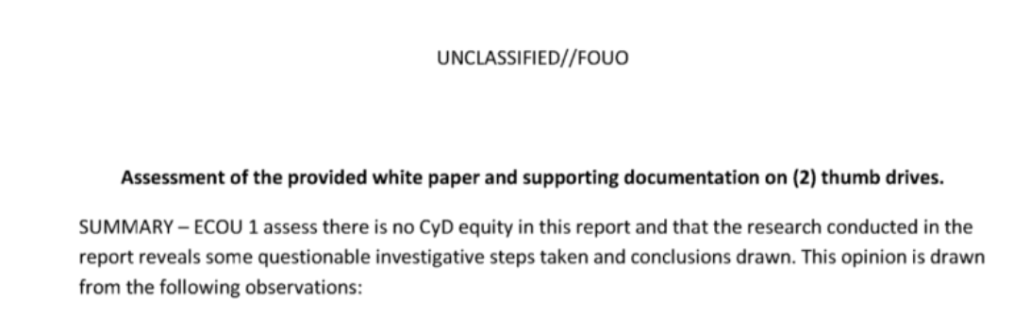

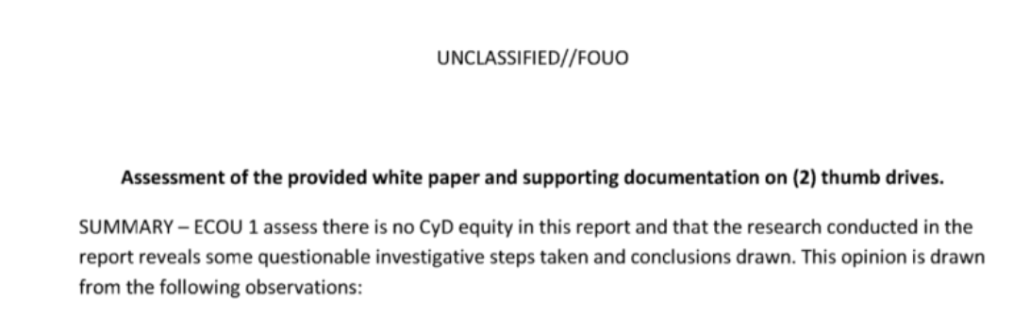

Here’s what Hellman’s own report looks like:

There’s a unit — ECOU1 — but the names of the individual agents appear nowhere in the report. The report is not dated. It does not specifically identify the white papers and thumb drives by control numbers, something key to evidentiary analysis.

It has none of the markers of regularity you’d expect from the FBI. Hellman’s own analysis doesn’t meet the standards that DeFilippis uses to measure reliability.

This long-time Grand Rapids resident is furious that Hellman judged there was no hack

Everything above I write as a journalist who has tried to understand this story for almost six years. Between that and 18 years of covering national security cases, I hope I now have sufficient familiarity with it to know there are real problems with Hellman’s analysis.

But let me speak as someone who lived in Grand Rapids for most of this period, and had friends who had to deal with the aftermath of Spectrum Health appearing at the center of a politically contentious story.

Hellman had, as he testified, two jobs. First, he was supposed to determine whether there were any cyber equities, then he was supposed to do some insta-analysis of the data without first looking at the thumb drives.

According to Hellman, there was no hack.

I was asked to perform two tasks in tandem with Special Agent Batty, and our tasks were, number one, to look at this data, look at the data and look at the narrative that it came with and identify were there any what’s known as cyber equities. And by that it was, was there any allegation of a hacking. That’s what cyber division does. We investigate hacking. So was there an allegation that somebody or some company or some computer had been hacked. That was first.

[snip]

As I mentioned, the first piece was we had to identify was there any real allegation of hacking; and there was not. That was our first task by our supervisor. There was not.

[snip]

The allegation was that someone purported to find a secret communication channel between the Trump organization and Russia. And so we identified first that, no, we didn’t think that there was any cyber equity, meaning that there was probably nothing more for cyber to investigate further, if there was no hacking crime.

Except here’s what the white paper says about Spectrum, that Grand Rapids business that was swept up in this story.

The Spectrum Health IP address is a TOR exit node used exclusively by Alfa Bank. ie., Alfa Bank communications enter a Tor node somewhere in the world and those communications exit, presumably untraceable, at Spectrum Health There is absolutely no reason why Spectrum would want a Tor exit node on its system. (Indeed, Spectrum Health would not want a TOR node on its system because, by its nature, you never know what will come out of a TOR node, including child pornography and other legal content.)

We discovered that Spectrum Health is the victim of a network intrusion. Therefore, Spectrum Health may not know it has a TOR exit node on its network. Alternatively, the DeVos family may have people at Spectrum who know there is a TOR node. i.e., could have been placed there with inside help.

When faced with some anomalous activity that seemed to tie into the weird DNS traffic, the experts suggested that maybe the Spectrum hack related to the DNS anomaly.

To be clear, this Tor allegation is the the weakest part of this white paper. You will hear about this to no end over the next week. It was technically wrong.

But the allegation in the white paper is that maybe a recent hack of Spectrum Health is why it had this anomalous traffic with Trump’s marketing server. There’s your hack!!

Had the people at FBI’s cybersecurity side actually treated this as a possible compromise, it might have addressed the part of this story that never made any sense. And we might not, now, six years later, be arguing about what might explain it.

Let me be clear: I do think the white paper overstated its conclusions. I don’t think secret communication is the most obvious explanation here.

But there are hacks and then there are hacks in the testimony of DeFilippis’ star cybersecurity agent.

Update: Corrected an attribution to Batty instead of Hellman.

Update: Fixed my own timeline.

Update: Added link to Robert Graham’s analysis.

Update: This may be where Hellman gets his erroneous three week claim. There were two histograms included with the report. One, the close-up, does start around July 7.

But the broader scope shows look-ups earlier, very actively in June, but with a few stray ones in May.

The government didn’t include the pages and pages of logs that Batty complained about in this exhibit. Had they, it would be clear to jurors that this claim is false.

Update: Correction on two points. First, I think I’ve finally got the Lync exchange above correct between Batty and Hellman. As noted, Hellman complains that “it contains an absurd quantity of data” to which Batty responded, the data seemed “inserted to overwhelm and confuse the reader.”

Second, I was wading through exhibits this morning and found the exhibit of 19 pages of logs. Here’s just a subset of them, including logs that go back to May 2016. Hellman didn’t look even at the printed page of log files closely enough to realize his claim about three weeks was wrong. These data weren’t intended to overwhelm the reader. They were there to show how the anomaly accelerated during the election.