John Durham Fabricated His Basis to Criminalize Oppo Research

I’d like to talk about Durham’s treatment of what he calls the “Clinton Plan” in his report, an attempt to criminalize Hillary’s effort to hold Trump politically accountable for his coziness with Russia.

This part of the investigation was the core of Durham’s work. Charlie Savage noted that, after Durham found no evidence US intelligence targeted Trump by early 2020, he and Barr then turned to trying to blame Hillary for the FBI’s suspicions about Trump.

But by the spring of 2020, according to officials familiar with the inquiry, Mr. Durham’s effort to find intelligence abuses in the origins of the Russia investigation had come up empty.

Instead of wrapping up, Mr. Barr and Mr. Durham shifted to a different rationale, hunting for a basis to blame the Clinton campaign for suspicions surrounding myriad links Trump campaign associates had to Russia.

I’m going to variably refer to this as “Durham’s Clinton conspiracy theory,” because it’s what he imagines this might be: a criminal conspiracy to lie to the FBI, or “Russian intelligence,” which is what it is based on. Durham, however, names it the “Clinton Plan,” accepting as given that the Russian intelligence product he bases it on is truthful, even while admitting that the intelligence community believes it may not be. And as we’ll see, he omits part of the intelligence report to make it all about Hillary.

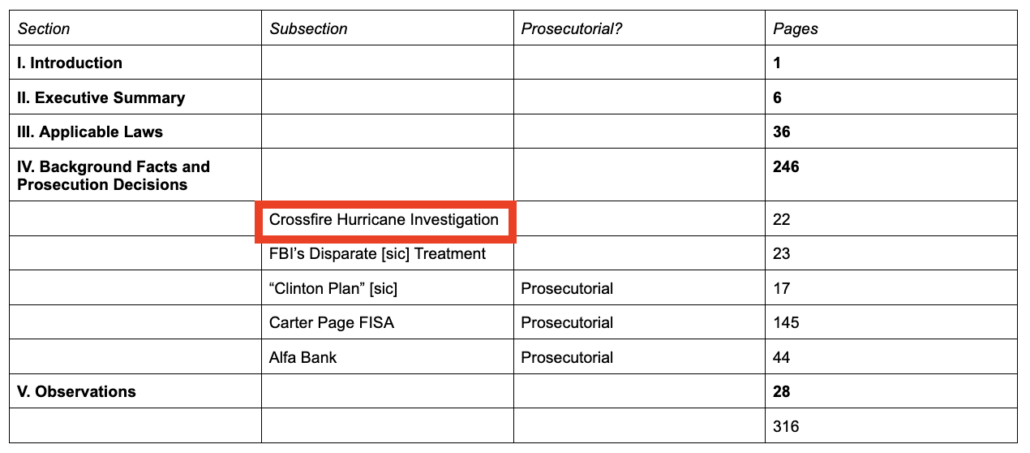

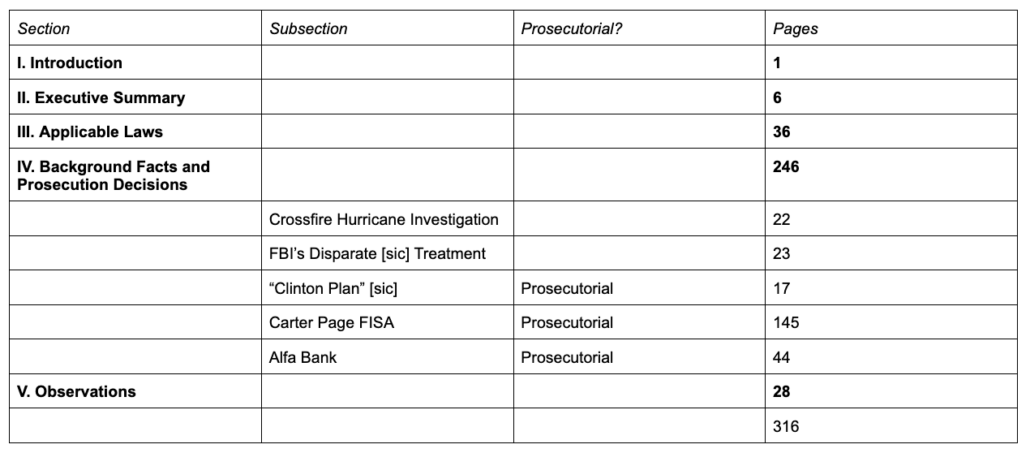

Durham’s Clinton conspiracy theory is the first mention of a potential crime in his description of the scope of his investigation (the first two bullets had significantly been covered by DOJ IG by the time Durham started his investigation and weren’t criminal at all).

Similarly, did the FBI properly consider other highly significant intelligence it received at virtually the same time as that used to predicate Crossfire Hurricane, but which related not to the Trump campaign, but rather to a purported Clinton campaign plan “to vilify Donald Trump by stirring up a scandal claiming interference by Russian security services,” which might have shed light on some of the Russia information the FBI was receiving from third parties, including the Steele Dossier, the Alfa Bank allegations and confidential human source (“CHS”) reporting? If not, were any provable federal crimes committed in failing to do so?

Only after that bullet does Durham list, in describing the scope of his criminal investigation, the possibility that people lied to the FBI, the only imagined crimes he discovered, and for which he got only acquittals.

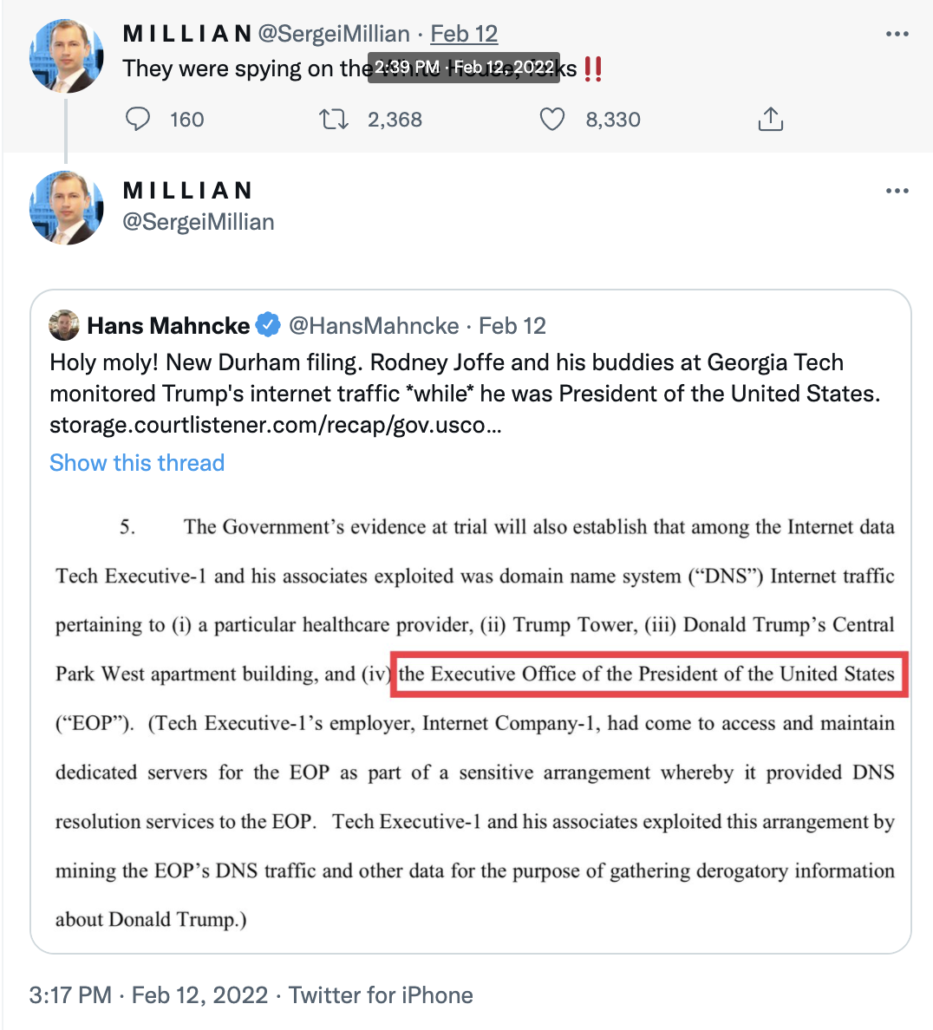

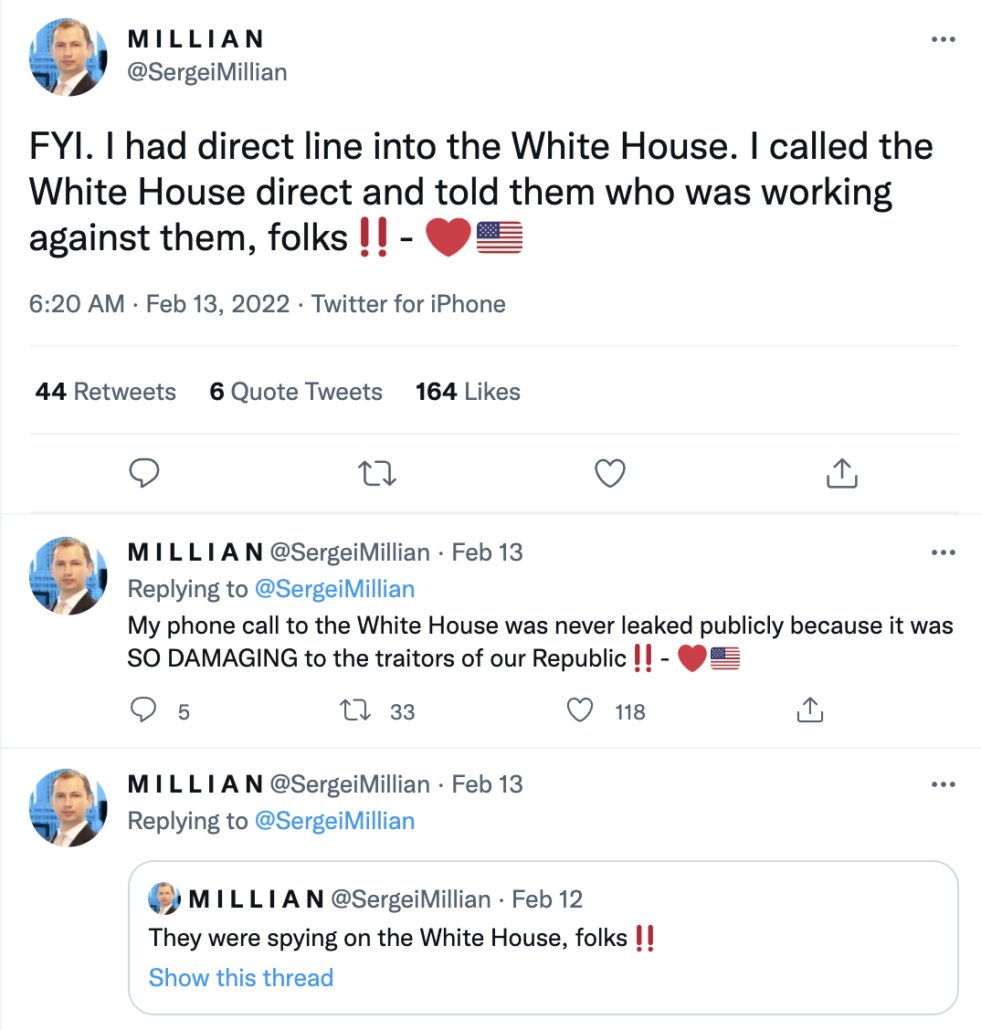

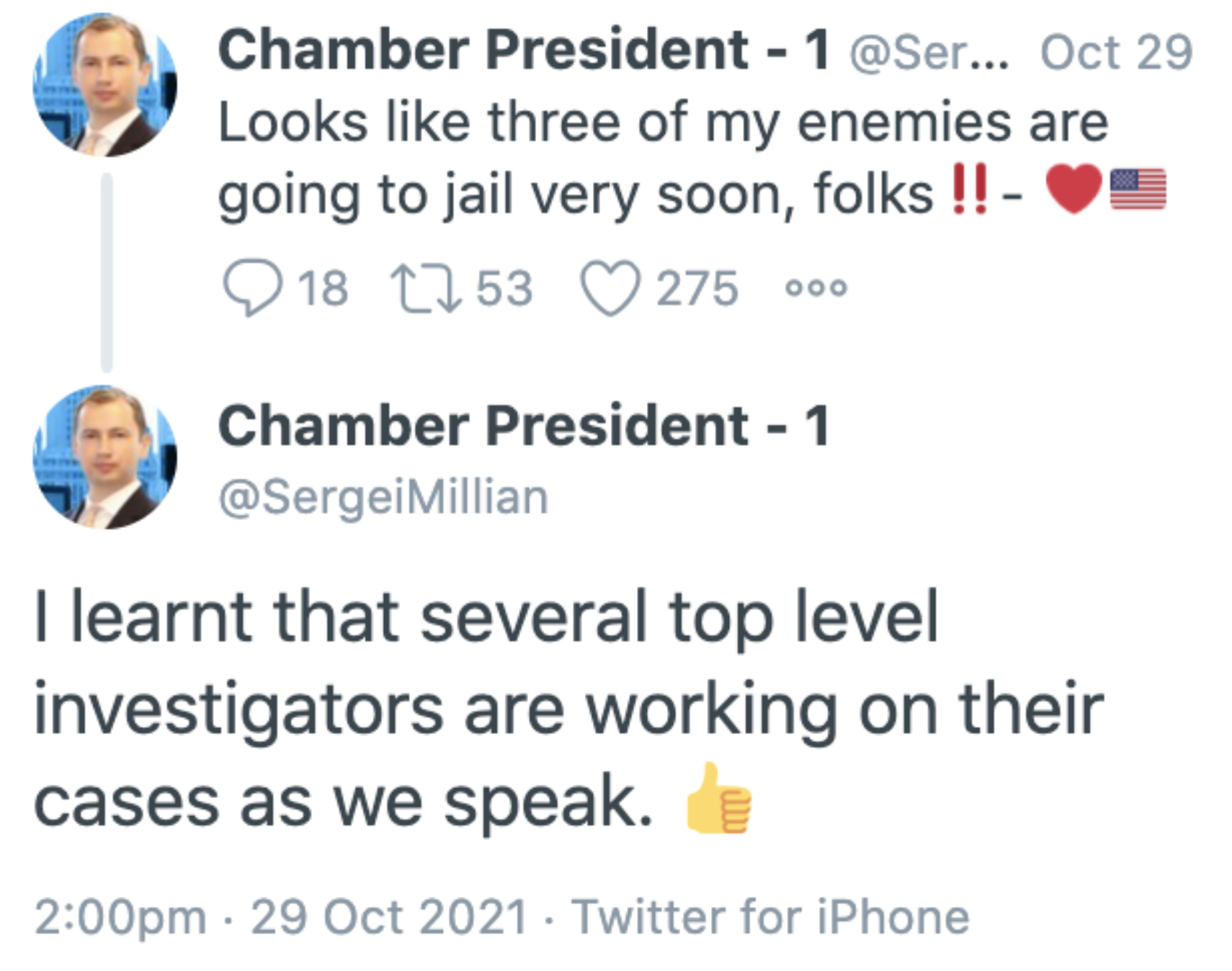

The order of these bullets tracks the known timeline of the investigation, which I laid out here: Durham didn’t fully develop his now-debunked theory that Michael Sussmann and Igor Danchenko lied to the FBI and then — building off that theory — come to believe Clinton had conspired to lie to the FBI. Rather, he worked in the opposite direction, pursuing the Clinton conspiracy theory first, and only after Nora Dannehy thwarted Durham’s attempts to release an interim report focused on that conspiracy theory just before the 2020 election, did he do key interviews collecting much of his evidence in the Alfa Bank and Danchenko investigations. Worse still, in both investigations, he never took obvious steps (like checking Jim Baker’s iCloud, or interviewing the Clinton staffers Sussmann allegedly coordinated with, or interviewing Sergei Millian, to say nothing of interviewing George Papadopoulos, which he never did) until months after indicting the two men. Everything happened in reverse order than it should have if he were following the evidence.

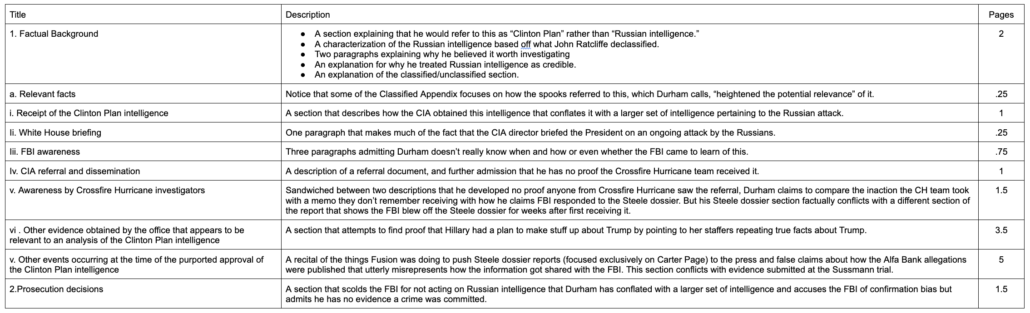

The section describing his Clinton conspiracy theory makes up almost 18 pages of the report, about 5% of the total. Here’s a summary of that section:

While I won’t focus on it, note that about a third of this section consists of complaints about the Steele dossier and Fusion, some of which conflicts with his complaints about the Steele dossier elsewhere, some of which ignores evidence submitted at the Sussmann trial.

Even on its face, there are real problems with Durham’s Clinton conspiracy theory. As Phil Bump (one, two) and Dan Friedman already showed, Hillary’s concerns about Trump couldn’t have been the cause of the investigation into Trump. By the time (a Russian intelligence product claimed) that Hillary approved a plan to tie Trump to Russia on July 26, 2016, the events that would lead FBI to open an investigation were already in place. Here’s Friedman:

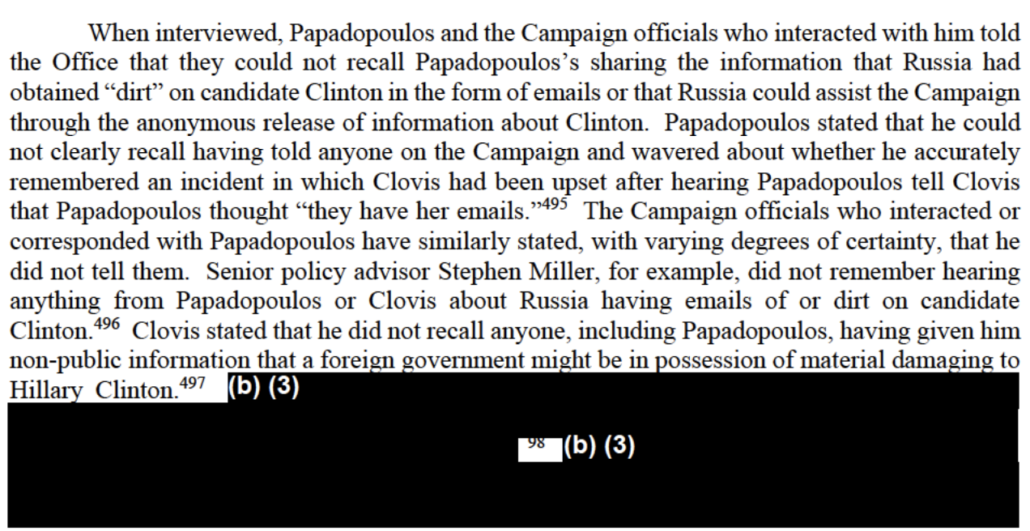

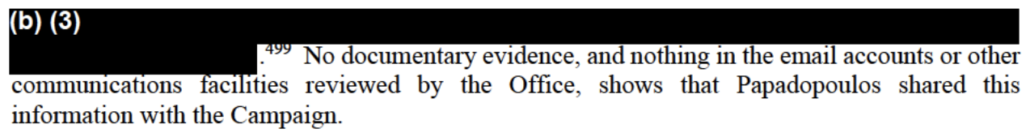

This isn’t just false. It would require time travel. Durham himself confirms that the FBI launched its investigation into Trump and Russia based on events that occurred months prior to Clinton’s alleged July 26 approval of the plan. In April 2016, George Papadopoulos, a foreign policy adviser to the Trump campaign, met with a professor with Kremlin ties, who informed him that Russia “had obtained ‘dirt’ on…Clinton in the form of thousands of emails,” as Robert Mueller’s final report noted. A week later, according to Mueller, Papadopoulos “suggested to a representative of a foreign government that the Trump Campaign had received indications from the Russian government that it could assist the Campaign through the anonymous release” of damaging material. When hacked Democratic emails were indeed published—by WikiLeaks on July 22—this foreign diplomat alerted US officials about what Papadopoulos had said. The FBI quickly launched an official investigation into the Trump campaign’s Russia ties in response to that tip, Durham notes, while arguing they should have begun only a “preliminary investigation.”

It was the same Russian hack, not Hillary Clinton, that drove media attention, even before the documents were leaked to the public.

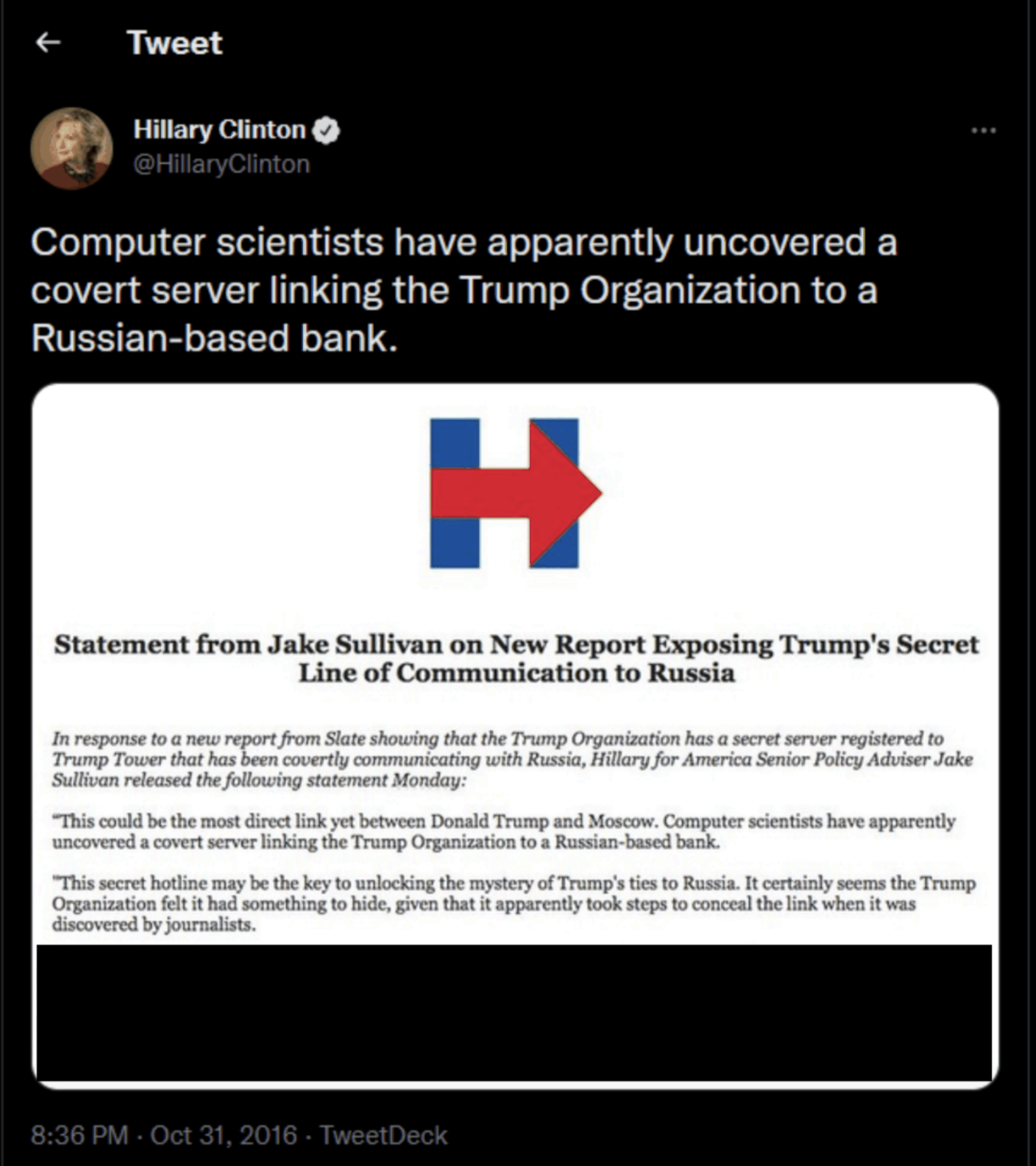

Ultimately, Durham hangs potential criminality (at least with respect to the FBI) on the Carter Page FISA applications, a suggestion that by not alerting the FISA Court that (Russia claimed) Hillary had this plan, the FBI was withholding what he calls “exculpatory” information. But in doing that, Durham conflates a Russian intelligence report making claims about Hillary with Hillary herself, something else Friedman rightly mocks.

To figure out how an American presidential campaign supposedly went about attacking a rival campaign, Durham relied on information US intelligence gathered on claims made by Russian intelligence agents about what they supposedly found by spying on Americans. That’s a pretty roundabout way to learn the kind of information you’d expect to see in “Playbook.” And this game of spy telephone was actually even longer than Durham details. According to the New York Times, US spies obtained their “insight” into Russian intelligence thinking from Dutch intelligence, which was spying on the Russians as the Russians spied on Americans. Durham seems to have found no other confirmation for his “Clinton Plan intelligence.” That’s reason enough for skepticism.

But there is a bigger problem. Russian security services did hack Clinton’s campaign to help Trump, according to the entire US intelligence community and the Senate Intelligence Committee. Yet Durham relies on those Russian spies for insight into how Clinton reacted to the hack. That is like the cops citing a bank robber who says the bank framed him.

Given how selective Durham is about how he treats Russian disinformation, this is a grave problem for his project, which I’ll return to.

But there are far more problems with Durham’s conspiracy theory.

Durham invents out of thin air that Hillary’s plan included false information

First, it’s not just that Durham focused his entire investigation on potential Russian disinformation with little worry about doing so.

At least per what is in the unclassified report, Durham added something to the Russian intelligence product: That Hillary had a plan to spread “false” information. Durham’s first paragraph explaining why the Russian intelligence claim about a Hillary plan is important claims:

First, the Clinton Plan intelligence itself and on its face arguably suggested that private actors affiliated with the Clinton campaign were seeking in 2016 to promote a false or exaggerated narrative to the public and to U.S. government agencies about Trump’s possible ties to Russia. [my emphasis]

Durham bases his entire pursuit of this piece of Russian intelligence on his judgment that the Russian intelligence “arguably suggested” Hillary’s people were going to pursue a “false or exaggerated” narrative to tie Trump to Russia. But the notion that this narrative would be — would have to be! — false is nowhere in any of the three formulations of the intelligence Durham describes in his unclassified report.

U.S Presidential candidate Hillary Clinton had approved a campaign plan to stir up a scandal against U.S. Presidential candidate Donald Trump by tying him to Putin and the Russians’ hacking of the Democratic National Committee.

[snip]

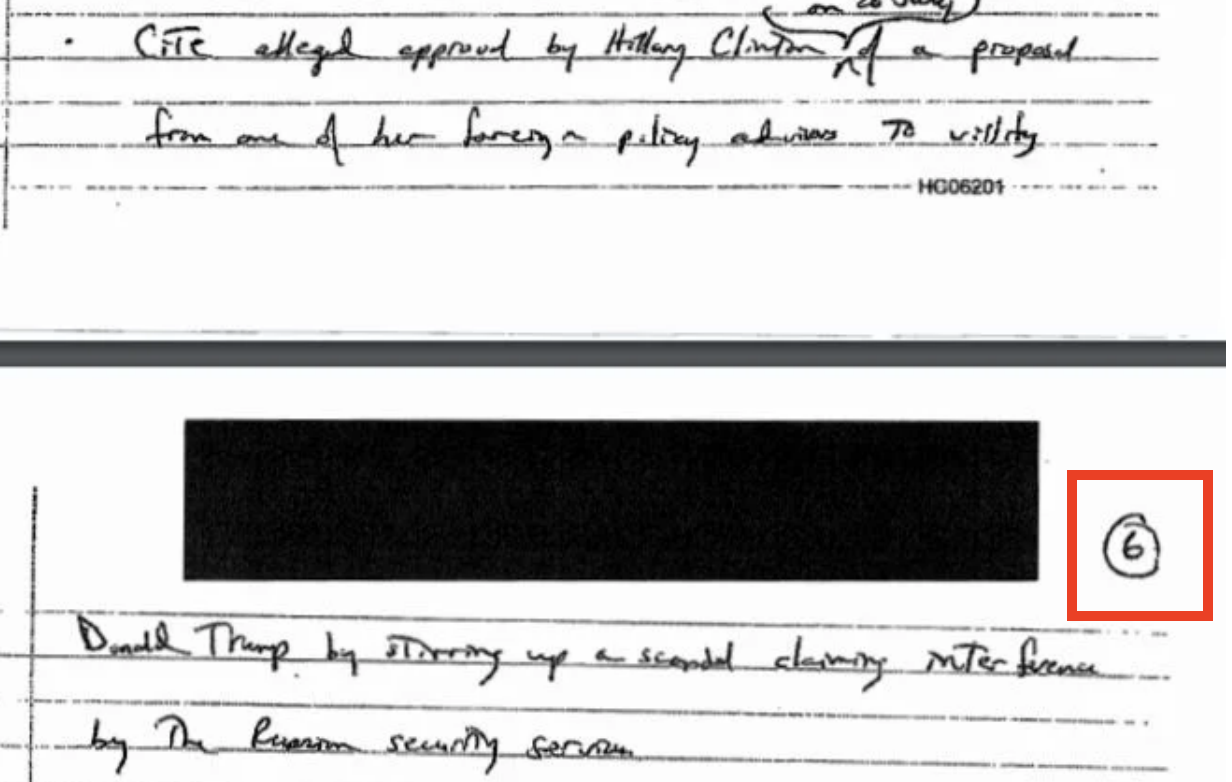

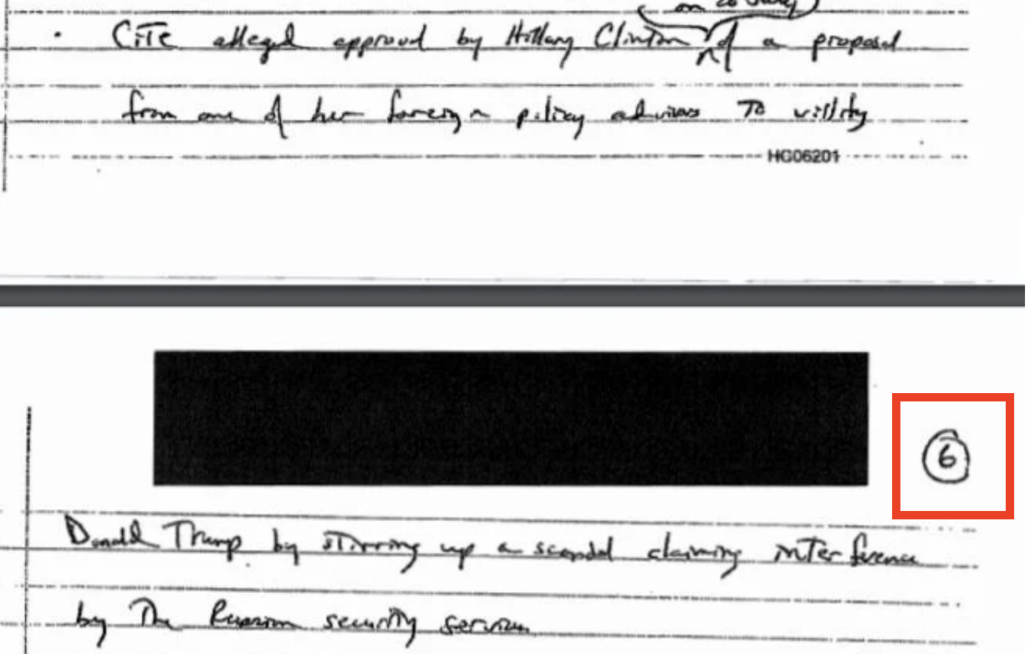

CIA Director Brennan subsequently briefed President Obama and other senior national security officials on the intelligence, including the “alleged approval by Hillary Clinton on July 26, 2016 of a proposal from one of her foreign policy advisors to vilify Donald Trump by stirring up a scandal claiming interference by Russian security services.”

[snip]

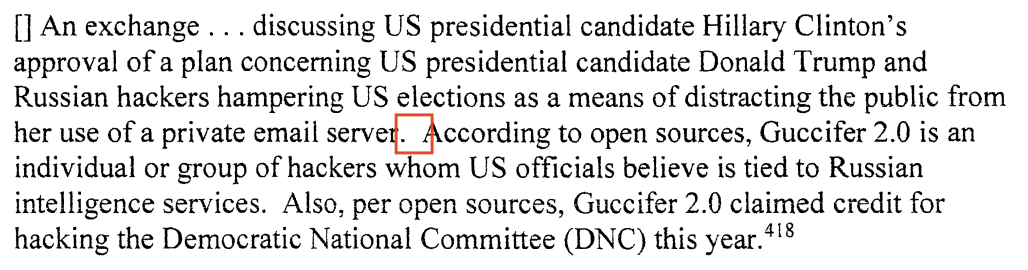

U.S. Presidential candidate Hillary Clinton’s approval of a plan concerning U.S. Presidential candidate Donald Trump and Russian hackers hampering U.S. elections as a means of distracting the public from her use of a private mail server.

Even the Russians were only claiming that Hillary would tie Trump to the hacking targeting her. The Russians didn’t claim Hillary would lie to do so. Yet Durham justifies this prong of investigation by adding something to the Russian intelligence that wasn’t in it: that tying Trump to Russia would “arguably” require false information.

That’s an utterly critical addition to what was actually contained in the Russian intelligence, because — as Durham noted in a footnote to this paragraph — oppo research is not itself illegal. It only becomes illegal if you intentionally lie to the government about it.

393 To be clear, the Office did not and does not view the potential existence of a political plan by one campaign to spread negative claims about its opponent as illegal or criminal in any respect. As prosecutors and the Court reminded the jury in the Sussmann trial, opposition research is commonplace in Washington, D.C. and elsewhere, is conducted by actors of all political parties, and is not a basis in and of itself for criminal liability. Rather, only if the evidence supported the latter of the two conditions described above-i.e., if there was an intent by the Clinton campaign or its personnel to knowingly provide false information to the government-would such conduct potentially support criminal charges.

Never mind that Durham never developed evidence that the Hillary campaign wanted or intended to privately share either the Steele dossier or the Alfa Bank allegations with the FBI. In fact, his report provides affirmative evidence that the Hillary campaign wanted nothing to do with the FBI, because it had already so damaged her campaign.

Without Durham’s invention — something that he made up out of thin air! — that Hillary planned to spread false information, Durham had no business spending three years investigating this. And remember, much of his investigation on Danchenko and the Alfa Bank allegations happened a year after he started pursuing his Clinton conspiracy theory, and two juries ultimately rejected his accusations that even the people who did share information with the FBI intentionally shared false information.

That’s one of many reasons why it matters that Durham so assiduously ignores all the evidence that Trump really was tied to Russia — that Mueller really did find hundreds of such ties, including a slew that Trump and his closest associates lied to the FBI to hide.

By the time Hillary allegedly approved this plan, on July 26, Trump had publicly hired a campaign manager with close ties to Russia, his foreign policy advisor had publicly made pro-Russian comments while speaking in Moscow, and he himself had publicly attacked NATO. The next day (and the day before the CIA discovered this), Trump publicly called for Russia to help him and publicly floated recognizing Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Even just on what was public, Hillary wouldn’t have had to invent anything.

But Russia knew about far more that wasn’t public. In January, Michael Cohen contacted the Kremlin to pursue a real estate deal in Moscow, involving both GRU and a sanctioned bank, something Trump would lie publicly about on July 27. In April, George Papadopoulos got an early warning of this operation. In May, Paul Manafort started sending polling data via Konstantin Kilimnik to Oleg Deripaska. In June, Trump’s failson accepted a meeting from the son of a Russian Oligarch promising dirt on Hillary. If you believe Rick Gates, Roger Stone claimed he was in contact with Guccifer 2.0 before the persona went public in June, and on July 25 (the day before the Russians claimed Hillary approved this purported plan), Manafort asked Stone to reach out to WikiLeaks and find out what else they had. The only one of these details that Russia didn’t definitely know was that Stone was pursuing WikiLeaks. By the time it wrote up that intelligence report, Russia was involved in all the rest of it.

And as I noted, Durham hid most of these non-public details. He hid the abundant evidence that Hillary wouldn’t have needed to make false claims, because the public and private reality all confirmed what Russia claimed Hillary was going to claim: that Trump had ties to Russia, ties he was hiding from voters.

Durham invents something that wasn’t in the Russian intelligence report he relies on, even while hiding abundant evidence that Hillary would have no reason to make stuff up, because there was so much public that was already damning.

Durham uses Hillary’s focus on true events as proof of his false claims

After inventing the claim that Russia said Hillary would rely on false information to tie Trump to the Russian operation, Durham points to Clinton’s focus on true things as evidence that Clinton really did have such a plan. In section vi, which Durham describes as, “Other evidence obtained by the office that appears to be relevant to an analysis of the Clinton Plan intelligence,” Durham uses several entirely true things that Hillary’s foreign policy advisors did, two of which precede the date when (the Russian intelligence report claims) Hillary approved a plan to focus on Trump, to try to prove that such a plan existed.

The section is punctuated with one after another Hillary staffer, and Hillary herself, saying that no such plan existed, but in spite of that, Durham spins three pieces of documentary evidence to claim it supports his conspiracy theory. The documentary evidence cited starts with a July 27 letter-writing effort to condemn Trump’s attacks on NATO.

We are writing to enlist your support for the attached public statement. Both of us are Hillary Clinton supporters and advisors but hope that this statement could be signed by a bipartisan group[.] Donald Trump’s repeated denigration of the NATO Alliance, his refusal to support our Article 5 obligations to our European allies and his kid glove treatment of Russia and Vladimir Putin are among the most reckless statements made by a Presidential candidate in memory.

This letter wasn’t even oppo research: It was mainstream opinion about a true fact about Trump.

Durham’s focus on this is exactly analogous to GOP efforts to attack a completely true letter former spooks wrote expressing their opinion that the Hunter Biden laptop looked like a Russian information operation, which Republican Congressmen have falsely depicted as a claim about disinformation. It’s even worse though, because Durham points to the mere expression of an opinion as evidence of criminal intent. True (and solidly within mainstream) opinion equals false and criminal in Durham’s book.

Then Durham turns to a Hillary staffer’s early July effort to follow-up on Franklin Foer’s July 4, 2016 review of Trump’s very real Russian ties. The article itself is really inconvenient for Durham’s narrative, because it summarizes all the absolutely true reasons (in addition to the ones I listed above) why Trump’s Russian ties were suspect, including an accurate description of why Carter Page’s fawning praise for Russia was so alarming. The article effectively proves this was a press concern before Hillary allegedly approved a plan to make it one. Given Foer’s later ties to Fusion, this entirely accurate article likely also relies on Fusion research, but Durham puts it in this section rather than the 5-page Fusion subsection, perhaps to hide that Fusion’s open source research largely held up. Perhaps because this Foer article itself undermines Durham’s narrative in various ways, Durham claimed this follow-up pertained to this June 2020 Foer article rather than the one written in July 2016, which would require an even more time travel than what Friedman described. Did Durham read the real article here and realize how badly it undermined all his claims about Fusion and Hillary and so cite one written four years later?

Insanely, however, Durham claims that this July 5 attempted follow-up, “provide[s] some support for the notion that the Clinton campaign was engaged in an effort or plan in late July 2016 to encourage scrutiny of Trump’s potential ties to Russia.” Durham cites a Clinton staffer’s focus on Trump’s true ties to Russia as proof Hillary approved — three weeks later — a plan to invent such ties. Again, true equals false.

Perhaps the craziest of all, buried deep in his report, Durham claims that Hillary’s staffers’ interest in finding out whether the FBI was actually investigating the crime committed against her — without any tie to Trump — is proof that Hillary had a plan targeting Trump.

In addition, on July 25, 2016, Foreign Policy Advisor-1 had the following text message exchange with Foreign Policy Advisor-2:

[Foreign Policy Advisor-2]: Can you see if [Special Assistant to the President and National Security Council member] will tell you if there is a formal fbi or other investigation into the hack?

[Foreign Policy Advisor-1]: [She] won’t say anything more to me. Sorry. Told me [she] went as far as [she] could.

[Foreign Policy Advisor-2]: Ok. Do you have others who might?

[Foreign Policy Advisor-1]: Has [Individual-2] tried [her]? Curious if [she] would react differently to [Individual-2]? can also try OVP [Office of the Vice President]. They might say more.

[Foreign Policy Advisor-2]: I don’t know if he has but can ask. Would also be good to try ovp, and anyone in IC [intelligence community]

[Foreign Policy Advisor-1]: Left messages for OVP but politico just sent me a push notification stating that they are indeed investigating.

[Foreign Policy Advisor-2]: Fbi just put our [sic] statement. Thx454

Remember: Durham accuses the FBI of confirmation bias, but here he uses a victim’s attempt to find out whether the crime committed against her was being investigated as evidence that, instead, she was victimizing Trump.

More problematic for Durham’s conspiracy theory, emails the Special Counsel only sought out in response to Sussmann’s discovery requests show that Sussmann knew of the investigation (because he was helping the FBI conduct it), proving that he had no ties with the people Durham imagined were behind this conspiracy theory.

In fact, FBI’s Assistant Director would concede to Sussmann that he should have consulted with the campaign before making such a public statement.

First let me apologize for any perceived or actual disconnect on this matter. I agree fully that when making statements to the media and others, we need to be in lock step with victims and partners. In this case, it appears we were not.

The FBI admitted it fucked up by not being more forthcoming about the status of the investigation. But Durham takes an effort to learn about whether there even was an investigation and claims it is evidence that victim may have committed a crime. This is the digital equivalent of slut-shaming, criminally investigating Hillary because she was hacked.

Durham’s report takes true stuff, some of it unrelated to Trump and other parts of it before the purported plan, as evidence that Hillary wanted to make false claims. And remember, these true details that Durham adopts to support his invented claim that Hillary was pursuing a false narrative are things Durham relies on to justify adopting a Russian intelligence product as the backbone of his investigation.

Given how shoddy this stuff is, I can only imagine what additional stuff he pointed to in his classified summary.

What Durham calls “Clinton Plan” is actually the Hillary-and-Guccifer intelligence

Time for a detour about Guccifer 2.0.

Remember how Durham omitted, without an ellipsis, damning information about Sam Clovis?

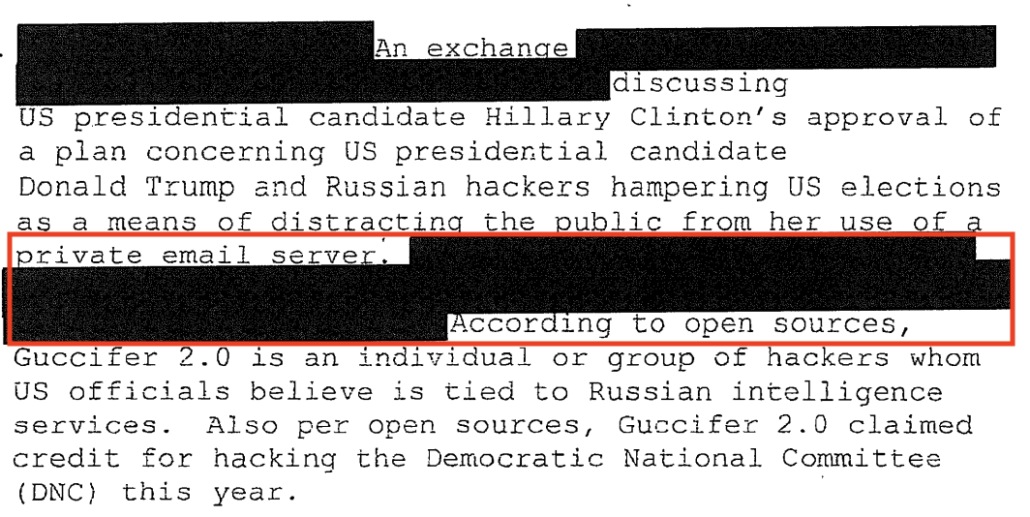

He similarly omitted two redacted lines in his presentation of the CIA referral of the Russian intelligence about Hillary and Guccifer 2.0. Here’s what it looks like in his report, with Durham’s omission marked:

Here’s what the original looks like, with the redaction Durham omitted marked.

I don’t know what is behind the redaction. Given what Durham did with the Clovis information, it probably doesn’t help his narrative. And given that Durham barely mentions Roger Stone and definitely doesn’t mention the rat-fucker’s suspected advance discussions with Guccifer 2.0, and given that his lead prosecutor criticized DARPA investigators for trying to identify Guccifer 2.0, the redaction is suspect. At the very least though, he should be referring to this not as “Clinton Plan intelligence,” but as “Hillary-and-Guccifer intelligence,” because that’s how it got packaged up for the FBI.

And if he treated this as Hillary-and-Guccifer intelligence, Durham might consider why the FBI didn’t begin to look at Roger Stone’s ties to Guccifer until almost a year after opening Crossfire Hurricane — but that would provide proof that the FBI wasn’t aggressive enough in their investigation of Trump, not that they were too aggressive.

Durham conflates reporting on Russia’s attack on the US with intelligence about Hillary

Durham’s failure to note the two-line redaction about Guccifer 2.0 matters because of something else he does.

First, note that this intelligence, if true, seems to reflect the collection by Russian spy agencies of recent communications between Hillary’s close associates (which would be explained in the second redaction). So if the intelligence were true, it would reflect a Presidential candidate’s associates being wiretapped by foreign spies. But Durham isn’t interested in that part of it. He’s interested in the content that Russia allegedly intercepted, not the the claimed intercept itself.

Key to Durham’s claim that the content of what Russia claimed to have intercepted from Hillary associates, rather than the claimed interception itself, is important is that John Brennan briefed it, the content, “expeditiously” to President Obama. But throughout this section, Durham plays word games to suggest a larger collection of intelligence is the same thing as the intelligence pertaining to Hillary(-and-Guccifer). As you read this section, imagine how it would read if instead of “Clinton Plan,” it read, “the intercept of Hillary’s associates.”

The Intelligence Community received the Clinton Plan intelligence in late July 2016. 397 The official who initially received the information immediately recognized its importance including its relevance to the U.S. presidential election- and acted quickly to make CIA leadership aware of it. 398

[snip]

Immediately after communicating with the President, Comey, and DNI Clapper to discuss relevant intelligence, Director Brennan and other agency officials took steps to ensure that dissemination of intelligence related to Russia’s election interference efforts, including the Clinton Plan intelligence, would be limited to protect sensitive information and prevent leaks.404

[snip]

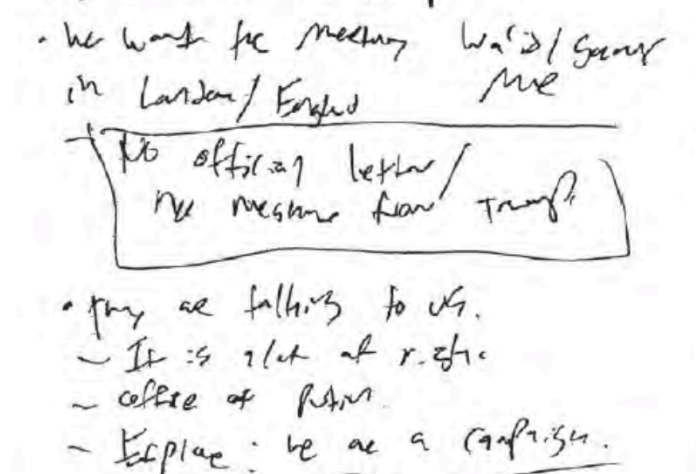

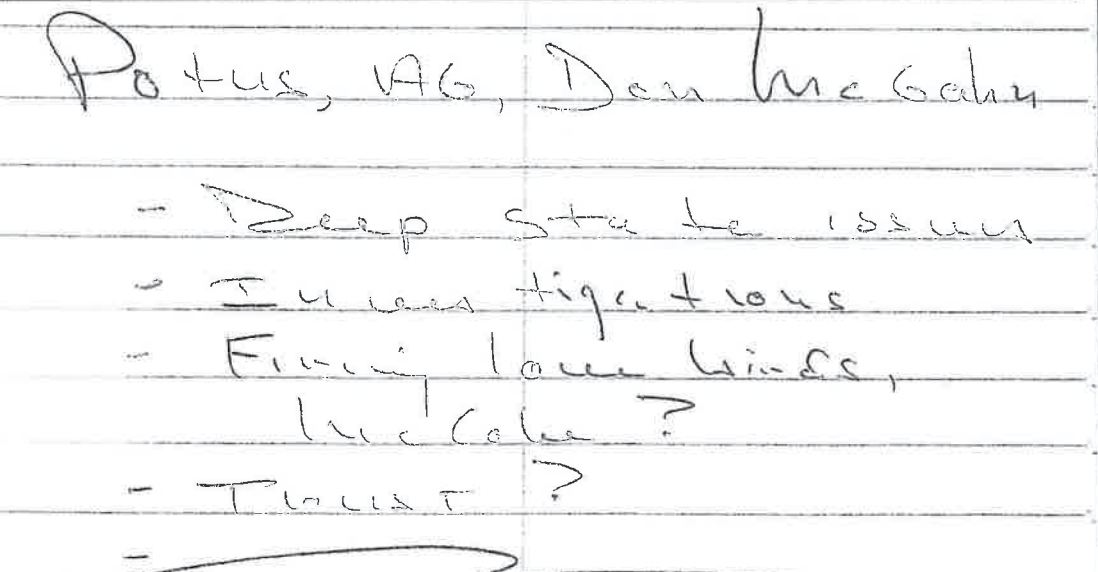

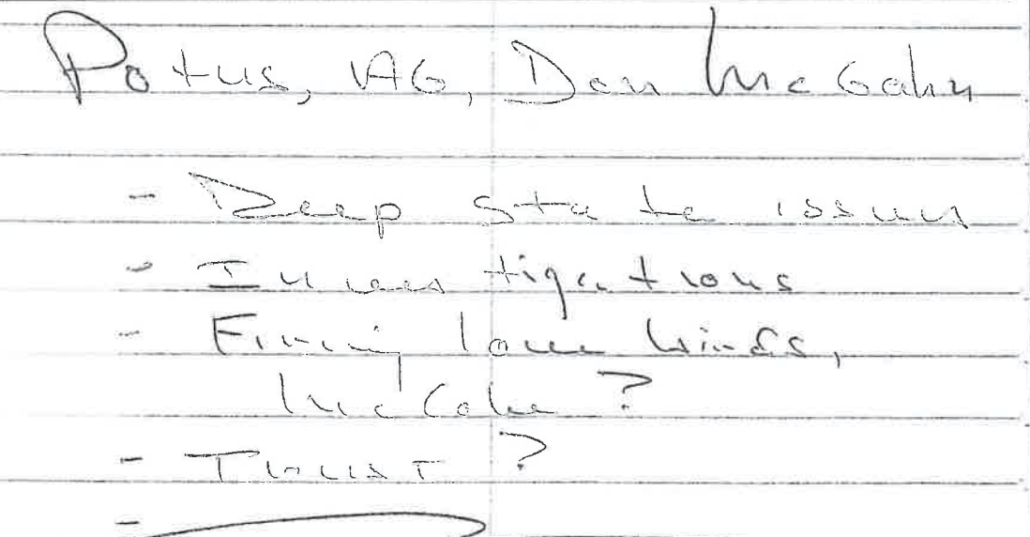

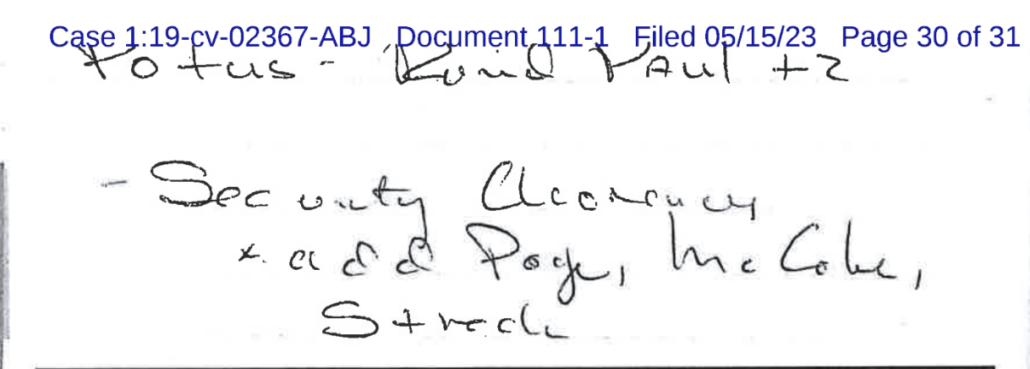

On August 3, 2016, within days of receiving the Clinton Plan intelligence, Director Brennan met with the President, Vice President and other senior Administration officials, including but not limited to the Attorney General (who participated remotely) and the FBI Director, in the White House Situation Room to discuss Russian election interference efforts. 406 According to Brennan’s handwritten notes and his recollections from the meeting, he briefed on relevant intelligence known to date on Russian election interference, including the Clinton Plan intelligence. 407 Specifically, Director Brennan’s declassified handwritten notes reflect that he briefed the meeting’s participants regarding the “alleged approval by Hillary Clinton on 26 July of a proposal from one of her [campaign] advisors to vilify Donald Trump by stirring up a scandal claiming interference by the Russian security services.”408

[snip]

In late September 2016, high-ranking U.S. national security officials, including Comey and Clapper, received an intelligence product on Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election that included the Clinton Plan intelligence. 421

[snip]

CIA Director Brennan and other intelligence officials recognized the significance of the intelligence by expeditiously briefing it to the President, Vice President, the Director of National Intelligence, the Attorney General, the Director of the FBI, and other senior administration officials. 491 [my emphasis]

Virtually all these references are to the wider body of intelligence the CIA was collecting on Russia’s targeting of Hillary, and the one that’s not — the reference to the discovery of the intelligence — almost certainly refers to the intelligence shared by the Dutch. Nevertheless, Durham uses the urgency of the intelligence about an ongoing attack to claim the importance of the Hillary-and-Guccifer intelligence.

The Hillary stuff — and whatever reference to Guccifer it included — was just one piece of intelligence among a bunch of intelligence. It probably wasn’t considered all that important a part of that intelligence, because it only appears on pages 5 and 6 of the notes taken from Brennan’s briefing of the intelligence.

In fact, Durham’s description of Brennan’s interview suggests that Brennan didn’t even consider this to be a piece of intelligence about Hillary. Indeed, he thought the intelligence was about Russia hacking Hillary, not Hillary making a plan to talk about being hacked by Russia.

When interviewed, Brennan generally recalled reviewing the materials but stated he did not recall focusing specifically on its assertions regarding the Clinton campaign’s purported plan. 400 Brennan recalled instead focusing on Russia’s role in hacking the DNC. 401

On July 28, 2016, Director Brennan met with President Obama and other White House personnel, during which Brennan and the President discussed intelligence relevant to the 2016 presidential election as well as the potential creation of an inter-agency Fusion Cell to synthesize and analyze intelligence about Russian malign influence on the 2016 presidential election. 402

Brennan’s impression that this intelligence was about Russia’s hack of the DNC would make sense if it were treated as a piece of intelligence about Russia intercepting communications of Hillary’s associates.

Durham’s conflation of the Hillary-and-Guccifer-specific intelligence with the wider body of intelligence continues as he describes how it got shared with the FBI. Again, imagine how this passage would read if you replaced “Clinton Plan” with “intercept of Hillary’s associates.”

It appears, however, that this occurred no later than August 22, 2016. On that date, an FBI cyber analyst (“Headquarters Analyst-2”) emailed a number of FBI employees, including Supervisory Intelligence Analyst Brian Auten and Section Chief Moffa, the most senior intelligence analysts on the Crossfire Hurricane team, to provide an update on Russian intelligence materials. 409 The email included a summary of the contents of the Clinton Plan intelligence. 410 The Office did not identify any replies or follow-up actions taken by FBI personnel as a result of this email.

When interviewed by the Office, Auten recalled that on September 2, 2016 – approximately ten days after Headquarters Analyst-2’s email – the official responsible for overseeing the Fusion Cell briefed Auten, Moffa, and other FBI personnel at FBI Headquarters regarding the Clinton Plan intelligence. 411

[snip]

FBI records reflect that by no later than that same date (September 2, 2016), then-FBI Assistant Director for Counterintelligence Bill Priestap was also aware of the specifics of the Clinton Plan intelligence as evidenced by his hand-written notes from an early morning meeting with Moffa, DAD Dina Corsi and Acting AD for Cyber Eric Sporre. 415

He falsely suggests that the entirety of an investigative referral memo regarded,

“U.S. Presidential candidate Hillary Clinton’s approval of a plan concerning U.S. Presidential candidate Donald Trump and Russian hackers hampering U.S. elections as a means of distracting the public from her use of a private mail server.”

In fact, the memo in which this intelligence got formally packaged up for the FBI included three things, paragraph a, paragraph b, and paragraph c (though the Hillary-and-Guccifer intelligence was first), with the introduction that these were simply “examples of information the CROSSFIRE HURRICANE fusion cell has gleaned to date,” not that they were particularly important examples. Nevertheless, Durham pretends the Hillary-and-Guccifer intelligence was the entirety of the memo.

There’s no reason to believe any of these briefings were about the Hillary-and-Guccifer intelligence specifically. Durham pretends there was a buzz among the intelligence agencies about Hillary, when in reality there was a buzz about Russia hacking Hillary that he presents as if it were primarily about Hillary.

Durham failed to coach witnesses into claiming they had received the FBI memo

In the section where Durham considers whether to charge some FBI agents for not doing more with the the Russian Hillary-and-Guccifer intelligence, he repeats his ploy of conflating the Hillary-and-Guccifer intelligence with the wider body of evidence to even deign to make a prosecutorial decision, though in this instance, he provides no reminder that the Hillary-and-Guccifer intelligence was just one of the things Brennan briefed to Obama, after five pages of other items.

The FBI thus failed to act on what should have been – when combined with other, incontrovertible facts – a clear warning sign that the FBI might then be the target of an effort to manipulate or influence the law enforcement process for political purposes during the 2016 presidential election. Indeed, CIA Director Brennan and other intelligence officials recognized the significance of the intelligence by expeditiously briefing it to the President, Vice President, the Director of National Intelligence, the Attorney General, the Director of the FBI, and other senior administration officials. 491

He lets the urgent import of an ongoing Russian hack to stand in for the import of this Hillary-and-Guccifer intelligence.

And that’s important, because Durham makes a prosecutorial decision about whether to charge FBI agents for how they responded to the intelligence that Russia claimed to have intercepted communications of Hillary personnel without proof that most of them ever read it.

As he describes, the top analytical people on the campaign learned of the claimed intercept of Hillary associates almost a month after CIA first obtained it.

On that date, an FBI cyber analyst (“Headquarters Analyst-2”) emailed a number of FBI employees, including Supervisory Intelligence Analyst Brian Auten and Section Chief Moffa, the most senior intelligence analysts on the Crossfire Hurricane team, to provide an update on Russian intelligence materials. 409 The email included a summary of the contents of the Clinton Plan intelligence. 410

There were in-person briefings for the top analytical people and the cyber people ten days later.

When interviewed by the Office, Auten recalled that on September 2, 2016 – approximately ten days after Headquarters Analyst-2’s email – the official responsible for overseeing the Fusion Cell briefed Auten, Moffa, and other FBI personnel at FBI Headquarters regarding the Clinton Plan intelligence. 411 Auten did not recall any FBI “operational” personnel (i.e., Crossfire Hurricane Agents) being present at the meeting. 412 The official verbally briefed the individuals regarding information that the CIA planned to send to the FBI in a written investigative referral, including the Clinton Plan intelligence information. 413

[snip]

Separate and apart from this meeting, FBI records reflect that by no later than that same date (September 2, 2016), then-FBI Assistant Director for Counterintelligence Bill Priestap was also aware of the specifics of the Clinton Plan intelligence as evidenced by his hand-written notes from an early morning meeting with Moffa, DAD Dina Corsi and Acting AD for Cyber Eric Sporre. 415

Durham describes the CIA writing a memo about what the fusion intelligence team had found — but he curiously never describes how or when it was sent.

Five days later, on September 7, 2016, the CIA completed its Referral Memo in response to an FBI request for relevant information reviewed by the Fusion Cell. 417

That’s important because Durham describes witness after witness describing that they had never seen it.

None of the FBI personnel who agreed to be interviewed could specifically recall receiving this Referral Memo.

[snip]

The Office showed portions of the Clinton Plan intelligence to a number of individuals who were actively involved in the Crossfire Hurricane investigation. Most advised they had never seen the intelligence before. For example, the original Supervisory Special Agent on the Crossfire Hurricane investigation, Supervisory Special Agent-1, reviewed the intelligence during one of his interviews with the Office. 428 After reading it, Supervisory Special Agent-I became visibly upset and emotional, left the interview room with his counsel, and subsequently returned to state emphatically that he had never been apprised of the Clinton Plan intelligence and had never seen the aforementioned Referral Memo. 42

[snip]

Former FBI General Counsel Baker also reviewed the Clinton Plan intelligence during one of his interviews with the Office. 431 Baker stated that he had neither seen nor heard of the Clinton Plan intelligence or the resulting Referral Memo prior to his interview with the Office.

In lieu of proof that it ever got sent, Durham reveals that Brian Auten might have hand-carried the memo to the team, but had no memory of doing so.

Auten stated that it was possible he hand-delivered this Referral Memo to the FBI, as he had done with numerous other referral memos,419 and noted that he typically shared referral memos with the rest of the Crossfire Hurricane investigative team, although he did not recall if he did so in this instance. 420

Note that two of the interviews on which this passage relies — a June 18, 2020 interview of Jim Baker and a July 26, 2021 interview of Auten — were shown to be highly problematic at trial.

In the former case, Durham called Baker back a week after an earlier interview; it’s the interview where Baker’s memory started changing fairly dramatically, under coaching from Durham, to coincide with the story Durham needed to have told to support his conspiracy theory.

Q. Did Mr. DeFilippis or Mr. Durham ask you to go back and think harder about certain things?

A. I don’t remember that.

Q. Well, do you remember when you met with them on June 18th of 2020? Do you remember generally that date?

A. I’ll take your word for it. I don’t remember that date specifically.

[snip]

Q. And at that meeting for the first time, you told them, After thinking about it further, you recalled being briefed at some point on an unrecalled date about the investigation involving the intrusion of the DNC computers and possibly learning at that briefing that Sussmann, who you knew from previous contacts, was representing the DNC on that matter.

Do you remember that that was the meeting where you said, “After further thought, Mr. Sussmann was representing the DNC at least on the hack?”

A. Again, I don’t remember that it was at that particular meeting, but I remember at some point acknowledging that.

Sussmann attorney Sean Berkowitz got Baker to admit that at the meeting, Durham only showed Baker the notes that matched the story the Special Counsel needed to be told, not those that utterly contradicted the story (and were consistent with a bunch of other evidence that at least four people at the FBI believed that Sussmann was there on behalf of the Democrats).

Q. Now, the government did not show you other people’s notes in that June of 2021 time period, correct?

A. At that point in time I don’t think they showed me anybody else’s notes.

[snip]

MR. BERKOWITZ: And if you could blow up, “The attorney brought to” — Page 2, I believe. Page 6.

A. I’m sorry, these are the notes we looked at yesterday.

Q. Right. These are the notes — just to be clear for everybody — March 6th of 2017. Did the FBI or anybody from Special Counsel Durham’s team show you these notes in an attempt to refresh your recollection of what happened in your interactions with Mr. Sussmann in 2016?

A. No.

The interview with Auten is similar.

As Danchenko attorney Danny Onorato laid out at trial, before Auten’s July 26, 2021 interview, Durham told Auten he was being criminally investigated.

Q Does July 26 of 2021 sound fair?

A Yes, it does.

Q Okay. And when you met with them for the first time after you were meeting with people for 25 or 30 hours, did your status change from a witness to a subject of an investigation?

A Yes, it did.

Q Okay. And in your work for the FBI, has anyone ever told you that you are a subject of a criminal inquiry?

A No.

Q Was that scary?

A Yes.

In addition to showing that at trial, Durham coached Auten into making an inaccurate statement about how Danchenko claimed Millian had called him, Onorato also showed — as Berkowitz had months earlier — that Durham had withheld documents that undermined Durham’s story and corroborated Danchenko’s during these earlier witness interviews.

In other words, both these interviews were shown at trial to have reflected coaching of witnesses to tell the story Durham wanted told, not the story reflected by the evidence. (Unsurprisingly, Durham never cites the trial testimony that disproves his claims in his report, yet another thing he accused the FBI of doing that he himself did.)

And even in spite of proof that Durham was coaching witnesses in these interviews, he still presented no affirmative evidence that the FBI investigators ever received the Fusion Cell memo. In the same way that all of Hillary’s people disclaimed any plan, the FBI investigators disclaimed having seen this memo.

Yet in spite of having no evidence that these people ever saw this memo, Durham compares how they responded to the Steele dossier with how they didn’t respond to this memo, and then generously decides not to charge anyone for doing nothing in response to a memo he has no proof they ever saw.

That’s how his conspiracy theory ended, after four years of trying to create evidence to support it, with him making an extended declination decision about a document he has no proof the FBI ever saw. His prosecutorial decision weighs whether the FBI “intentionally furthered” a Clinton plan to “frame” Trump with improper ties to Russia, as if he had presented proof there was such a plan.

The aforementioned facts reflect a rather startling and inexplicable failure to adequately consider and incorporate the Clinton Plan intelligence into the FBI’ s investigative decision-making in the Crossfire Hurricane investigation. Indeed, had the FBI opened the Crossfire Hurricane investigation as an assessment and, in turn, gathered and analyzed data in concert with the information from the Clinton Plan intelligence, it is likely that the information received would have been examined, at a minimum, with a more critical eye. A more deliberative examination would have increased the likelihood of alternative analytical hypotheses and reduced the risk of reputational damage both to the targets of the investigation as well as, ultimately, to the FBI.

The FBI thus failed to act on what should have been -when combined with other, incontrovertible facts – a clear warning sign that the FBI might then be the target of an effort to manipulate or influence the law enforcement process for political purposes during the 2016 presidential election. Indeed, CIA Director Brennan and other intelligence officials recognized the significance of the intelligence by expeditiously briefing it to the President, Vice President, the Director ofNational Intelligence, the Attorney General, the Director of the FBI, and other senior administration officials. 491 Whether or not the Clinton Plan intelligence was based on reliable or unreliable information, or was ultimately true or false, it should have prompted FBI personnel to immediately undertake an analysis of the information and to act with far greater care and caution when receiving, analyzing, and relying upon materials of partisan origins, such as the Steele Reports and the Alfa Bank allegations. The FBI also should have disseminated the Clinton Plan intelligence more widely among those responsible for the Crossfire Hurricane investigation so that they could effectively incorporate it into their analysis and decision-making, and their representations to the OI attorneys and, ultimately, the FISC. 492

[snip]

Although the evidence we collected revealed a troubling disregard for the Clinton Plan intelligence and potential confirmation bias in favor of continued investigative scrutiny of Trump and his associates, it did not yield evidence sufficient to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that any FBI or CIA officials494 intentionally furthered a Clinton campaign plan to frame or falsely accuse Trump of improper ties to Russia.

Again, to get to the point where Durham is making a prosecutorial decision about whether the FBI helped Hillary frame Trump, Durham has,

- Relied on proof that Hillary pointed to the true things that were damning enough

- Presented affirmative evidence that Hillary wouldn’t have approved of sharing the Alfa Bank anomaly with the FBI

- Been told, by two juries, that he couldn’t prove that anyone actually lied to the FBI

- Presented no evidence that the FBI investigators saw this memo

And yet virtually every Republican claims that this is what the Durham Report did conclude, that Hillary did have such a plan.

He made it up.

For the more than three years, John Durham criminally investigated whether Hillary framed Donald Trump. And that entire investigation is based on a premise that even he describes was only “arguably suggested” by the evidence on which he builds it.

In fact, Durham fabricated that entire part of it. He made up, out of thin air, his claim that a Russian intelligence report “suggested” Hillary was going to make false claims about Donald Trump rather than simply repeating all the true things that were damning enough.

The entire Durham Report was built on this fabrication, a fabrication he used to claim that Hillary was framing someone, instead of doing so himself.

Update: Durham himself submitted this email thread between Fusion and Foer showing that Fusion was heavily involved in Foer’s article and that their focus on Carter Page significantly preceded Page’s July speech in Russia.