Mankiw’s Tenth Principle: Society Faces A Short-Run Trade-off Between Inflation and Unemployment

The introduction to this series is here.

Part 1 is here.

Part 2 is here.

Part 3 is here.

Part 4 is here.

Part 5 is here.

Part 6 is here.

Part 7 is here.

Part 8 is here.

Part 9 is here.

Mankiw’s tenth principle of economics is: Society faces a short-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment. He admits that this is more controversial among economists than his other principles. He says that most believe this explanation:

- Increasing the amount of money in the economy stimulates the overall level of spending and thus the demand for goods and services.

- Higher demand may over time cause firms to raise their prices, but in the meantime, it also encourages them to hire more workers and produce a larger quantity of goods and services.

- More hiring means lower unemployment.

This line of reasoning leads to one final economy-wide trade-off: a short-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment.

This gives economic policy-makers a tool for influencing economic trends. “By changing the amount of money it prints”, says Mankiw, government can put more or less money into the economy, and thus influence unemployment, at least in the short run. The Great Crash of 2008 is an example. Mankiw explains that it was caused by “bad bets on the housing market”, and led to high unemployment and lower incomes. The Obama administration responded with a stimulus package of spending and tax cuts, and the Fed increased the amount of money in the economy, in an effort to reduce unemployment. He adds: “Some feared, however, that these policies might over time lead to an excessive level of inflation.”

The frightened people were, of course, proven absolutely wrong, though they won the policy argument with the imposition of the Sequester. The stimulus package was too small, though at least it more or less happened, and of course spending on the military increased, which helped, though it would have been nice to have something for the money besides the worthless F-35. This discussion is fleshed out beginning at about page 490 (in the 6th Ed.) with a long discussion of the Phillips Curve. This Wikipedia entry is at least cheaper than buying Mankiw’s book. for those not familiar with the subject.

This isn’t so much a principle in the sense of an axiom as it is a theorem, worked up from axioms. The source of the idea is a 1958 paper by William Phillips, showing an historical correlation between inflation and unemployment in the UK, and extended to US data by Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow. The correlation and the explanation worked together to persuade people that both the grounds of explanation and the relationship were more or less permanent features of the economy. The ideas behind the explanation are neoclassical, so the correlation served to validate those neoclassical ideas.

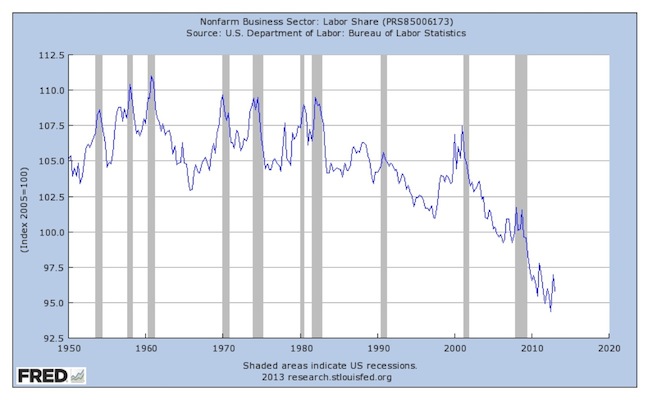

Recently the Wall Street Journal published an essay by Ben Leubsdorf discussing the current understanding of the Phillips Curve debate: The Fed Has a Theory. Trouble Is, the Proof Is Patchy. [Paywall]. Jared Bernstein discusses it in this post and links to this New York Times post; both are worth reading to see just how unhinged we are from the simple explanation offered by Mankiw. This chart is from the WSJ article.

To read the chart, select an expansion, find the line in that color, and look for the circle, which is the beginning of the period. Then follow the line as it moves showing the changes in inflation (y-axis) and unemployment (x-axis). Here’s Leubsdorf’s explanation:

But the simple link between U.S. unemployment and inflation described by the Phillips curve appeared to break down after the 1960s. High inflation coexisted with high unemployment in the 1970s. In the 1990s, the jobless rate fell as price pressures weakened. Over the past three years, inflation has declined despite a falling jobless rate.

Mankiw says there is dispute among economists about this, and Leubsdorf confirms that. He says that a recent WSJ survey found that 2/3 of economists “believed that the link exists.” Here’s a quote from a believer, Atlanta Fed President Dennis Lockhart.

“In the absence of direct evidence that inflation is in fact converging to the target and in the absence of compelling or convincing direct evidence, I think a policy maker has to act on the view that the basic relationship in the Phillips curve between inflation and employment will assert itself in a reasonable period of time as the economy tightens up ….

Economists are fully aware of the problems with the Phillips Curve, and there are plenty of attempts to make it better. This is from the conclusion of an April 2015 Working Paper by Laurence Ball and Sandeep Mazumder of the International Fund:

One of Mankiw’s (2014) ten principles of economics is, “Society faces a short-run tradeoff between inflation and unemployment.” This tradeoff, the Phillips curve, is critically important for monetary policy and for forecasting inflation. It would be extraordinarily useful to discover a specification of the Phillips curve that fits the data reliably. Unfortunately, researchers have repeatedly needed to modify the Phillips curve to fit new data. Friedman added expected inflation to the Samuelson-Solow specification.

Subsequent authors have added supply shocks (Gordon, 1982), time-variation in the Phillips-curve slope(Ball et al., 1988), and time-variation in the natural rate of unemployment (Staiger et al.,1997). Each modification helped explain past data, but, as Stock and Watson (2010) observe, the history of the Phillips curve “is one of apparently stable relationships falling apart upon publication.” Ball and Mazumder (2011) is a poignant example.

Even today people are looking for a way to find something useful in past data to predict future outcomes. As Leubsdorf noted, the Fed is using some version of this curve in deciding when to raise interest rates.

So, how does this fit with neoliberalism? One of the goals of neoliberal economics is the protection of established wealth. Inflation erodes wealth. Returns to capital may or may not keep up with inflation, depending on the strength of labor and other factors of production. Debtors are able to repay their debt in less valuable dollars, which erodes the assets of creditors. If the increased returns are less than the erosion, wealth suffers. As we have seen in the wake of the Great Crash, the governing power structure of neoliberalism demands that capital be protected whether in the form of equity or debt. This principle tells policy makers to put people out of work rather than suffer inflation.

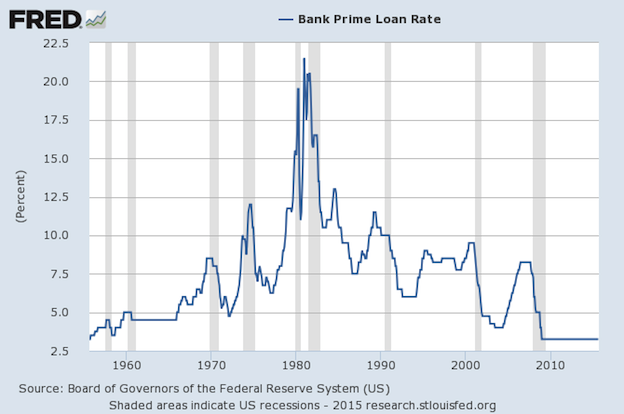

The Fed follows this principle. This is a chart of the labor share of income.

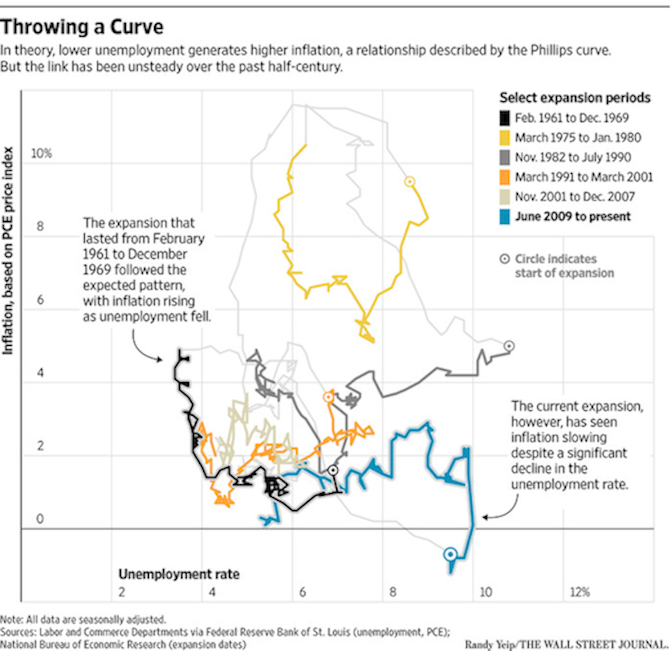

The gray vertical bars are recessions. The chart shows that as the labor share rises, we get a recession. The following chart shows bank prime rates.

As interest rates rise, we get recessions. With the exception of the recession that followed the Great Crash, it’s fair to say that all of these recessions were engineered by the Fed because of inflation or fear of inflation.

The implications are fascinating. Before the Great Crash, almost all US money was created by bank lending and credit expansion. Mankiw’s Principle No. 9 tells us that when too much money is created, we get inflation. The Phillips Curve tells the Fed it has to raise interest rates to stem inflation, and that it does so at the cost of putting people out of jobs. So, businesses lend and borrow too much, creating inflation or fear of inflation, and to solve the problem created by the failure of capitalists, the Fed makes sure only the working people pay the price, by losing their livelihoods, and lately, by watching their incomes stagnate or drop. And that is the outcome of applying Mankiw’s Principles of Economics: damaging workers to protect the rich.

Increases in wages are the only inflation, dontcha know? Management responds to wage inflation by cutting dollar production and then cutting productive capacity. It walks like a capital strike, talks like a capital strike, it must be a duck. Any time that management frets about not being able to hire enough workers, workers better be setting aside for the recession and layoffs.

Fight off those economic drones that want to take away your income and/or livelihood!

.

http://news.discovery.com/tech/robotics/invisible-sensor-dome-detects-spy-drones-150827.htm

omg. Economics of traveling in Michigan The first map looks exactly like ridiculous routes automatically chosen on Google maps …in Michigan. Probably because..potholes. :)

(sorry, I couldn’t resist)

Another one of where to start? I want to argue that printing money does not, of itself, cause inflation. You could print trillions and have zero impact if no one is able to spend it, like buy bombs or something. And that would require congressional approval. Or maybe drop it around town from a helicopter. That will likely cause an inflation, but even that is not guaranteed unless you drop enough money to affect demand.

Increased employment, similarly, does not of itself cause inflation. When you get employment near full employment it certainly will do that. And you can cause inflation in any industry, like building tanks or bombs, if you spend too much money there beyond short run capacity. And that could spread. Wars tend to do that, ask the leaders of Weimar.

Keynesian spending does not of itself cause inflation either. Deficits are not meaningful in a recession. If you have large deficits in full employment or near to it, you can expect an inflation.

Inflation is also a different animal. A few years ago oil got to $147 a barrel and in the 70s oil increased dramatically. That sort of inflation is a supply shock caused by monopolists. It is something like a crop failure and increased food prices. That is why inflation numbers generally omit those two items. Nonetheless an increase there spreads to other items as well. I also think we need to beware of one time inflation and one that generates on going inflation.

It is likely true that bankers will go bonkers over inflation, since their bets are often in fixed dollars. So too those living on fixed incomes. And Mickey D does not want an increased min wage since they may need to increase their prices a few cents. That one time inflation is something we should do.

this is old, very old, empirical information. nonetheless, inferences drawn from it are apparently still being peddled in a (major) textbook 50 years ex post factos, 50 years after the data (may have ) held true:

[… The source of the idea is a 1958 paper by William Phillips, showing an historical correlation between inflation and unemployment in the UK, and extended to US data by Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow. The correlation and the explanation worked together to persuade people that both the grounds of explanation and the relationship were more or less permanent features of the economy. The ideas behind the explanation are neoclassical, so the correlation served to validate those neoclassical ideas..

nowadays we have a surplus of trained labor and labor pools, aka factory towns, not just in the u.s. and europe, but all over the world – in china, india, indonesia, mexico, vietnam, …. wages and income in the u.s. have been stable or depressed for years.

.

.

http://america.aljazeera.com/opinions/2015/8/flat-wages-show-the-us-doesnt-have-a-labor-market.html

.

.

http://www.taxanalysts.com/www/features.nsf/Articles/C52956572546624F85257B1D004DE3FC

.

.

how do you get inflation under these circumstances?

.

how could an intellectually honest economist claim you would?

i would be inclined to argue, were i better educated in economics, that what inflation we now have is driven largely by market manipulation of commodities – electricity, oil, copper, beans, etc. – and by oligopolistic setting of artificially high prices to non-wealthy consumers – airlines, communications, etc.

Yep!

Where to begin? My head hurts. This is complete nonsense, all be it well within the confines of economic orthodoxy. I despair.

‘Growth’ is not going to save us. And my God, how can anyone say with a straight face that it is a dearth of money which plagues us.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7e/U.S._MZM_money_supply.png

http://goldseek.com/news/2009/1-12mh/11.png

More money isn’t going to save us and since money is debt that means more debt isn’t going to save us. Of course economic orthodoxy never never every discusses debt, or money either. Bernanke himself allowed that the Fed does not use measures of money and credit to determine monetary policy. Try to get your mind around that. I’ll repeat, money is not considered when setting monetary policy.

That said the Fed, whose business is money suffers from the law of instruments. Since their only tool is money they think money is the solution to everything, as in the guy with the hammer thinks everything is a nail. What Bernanke meant was monetary and credit aggregates, totals, are not included in their analysis. Rather they simply look at ever short term and make sure there is enough money, liquidity, in the financial system so it runs smoothly.

Oh well, forgetaboutit. As it all come undone it will be perfectly obvious to future generations that ‘Economics’ was insanity, an ideology. We are at the tail end of a gigantic global bubble. From within its confines it seems reasonable that ‘growth’ can go on forever. Please try to peek from outside the bubble.

Spend a few weeks here and try to begin to understand where we are. And please please please, do no try to impart partisan political understandings to these things.

http://creditbubblebulletin.blogspot.com/p/credit-bubble-bulletin.html

I don’t know what you mean by partisan politics. The democrats are just as hooked on neoliberalism as the republicans, and more effective at getting the will of the neoliberals done because of residual trust in the long-dead idea that the dems represent workers.

*

The serious issue of partisan politics is us against neoliberals of both parties.

RE Ed Walker and so RE orion, Right about neoliberalism and so right about partisanship, US style today. Talking not about rhetoric but about what is done, what happens.

Democrats talk about inequality and Republicans decry the very idea that it is talked about, as per neoliberal teachings, but both deliver it.

I am curious orion as to what partisan message you perceived in my post. I am truely at a loss as to what you perceive as partisan in that post. Not what you infer but what words you see that indicate partisanship.

happy to oblige. sorry you are so oblivious to your own messages:

.

“… since money is debt that means more debt isn’t going to save us. Of course economic orthodoxy never never every discusses debt, or money either…”.

and of course, there was your message i quoted from my #9 comment:

.

“…And please please please, do no try to impart partisan political understandings to these things…”

why would you feel the need to use the word “partisan” in the context of this column on economics ?

you’ll be lots happier (and closer to reality) if you can bring yourself to think of “money” as a lubricant to complex social organization rather than as “debt”.

the creditbubble.com weblog you approvingly cite is typical of the genre of earnest, goofball “i got the real inside scoop on the financial future” soothsayers who are always looking for suckers to advise:

.

http://creditbubblebulletin.blogspot.com/2015/05/my-weekly-commentary-paying-for-past.html

.

this particular edition of the creditbubble weblog is nothing if not partisan – ok, truthtelling in your view – featuring as it does the petersen institute and a propaganda conference it held, starring l. lindsey, r. fisher, and the deceitful republican political operative alan greenspan.

not that it matters in a dead thread, but

.

http://equitablegrowth.org/2015/08/30/must-read-mark-thoma-u-s-inflation-developments/

“…And please please please, do no try to impart partisan political understandings to these things…”

.

your lack of self-awareness is comical.

.

you clearly permit yourself to indulge in that which you forbid to all others.

ed walker –

[… It would be extraordinarily useful to discover a specification of the Phillips curve that fits the data reliably. Unfortunately, researchers have repeatedly needed to modify the Phillips curve to fit new data. Friedman added expected inflation to the Samuelson-Solow specification.

Subsequent authors have added supply shocks (Gordon, 1982), time-variation in the Phillips-curve slope(Ball et al., 1988), and time-variation in the natural rate of unemployment (Staiger et al.,1997). Each modification helped explain past data, but, as Stock and Watson (2010) observe, the history of the Phillips curve “is one of apparently stable relationships falling apart upon publication.” Ball and Mazumder (2011) is a poignant example. …]

if memory serves, thomas kuhn’s book on paradigm shifts in science focused on the ptolemaic vs the copernican explanation for planetary motions. the ptolemaic was always in need of amendment or supplementation to account for events it’s central theory did not explain well. the (later) copernican system explained planetary motions with a simpler system because it was in tune with physical reality (with n. copernicus’ data-thebased insights into the relation of the sun and planets).

it occurs to me that the perceived need among economists for perpetual jiggering with the phillips curve’s supporting data bears a close analogy to the ptolemaic system’s need for continual theoretical additions to account for discovered exceptions.

we’ve come full circle here :))