Deconstructing Neoclassical Utility

Several commenters have pointed out definitional problems with the term “utility” as used in neoclassical economics, including Tarheel Dem, rg and Alan. As I noted in the linked post, Samuelson and Nordhaus are careful to call utility a “ scientific construct”, and not a measurable thing. Philip Mirowski is very helpful in clarifying what this remarkable notion might mean. I’ve referred several times to this paper, Physics and the “Marginalist Revolution”, in which Mirowski offers a brief, perhaps too brief, explanation, which he incorporated into a dense, perhaps too dense, book, More Heat Than Light: Economics as Social Physics, Physics as Nature’s Economics. I’m slowly making my way through the book, but the paper is probably enough for a decent understanding of one issue.

Mirowski says that the four most important neoclassical economists were hooked on the physics of the day. All of them, Jevons, Pareto, Walras and Edgeworth, were trained in math and physics, and all had at least some acquaintance with the work of Jeremy Bentham. They were also quite explicit that their ideas were congruent with the emerging understanding of energy as a mathematical basis for a number of expanding areas of physics. He quotes Jevons as follows:

Utility only exists when there is on the one side the person wanting, and on the other the thing wanted… Just as the gravitating force of a material body depends not alone on the mass of that body, but upon the masses and relative positions and distances of the surrounding material bodies, so utility is an attraction between a wanting being and what is wanted. Citation omitted.

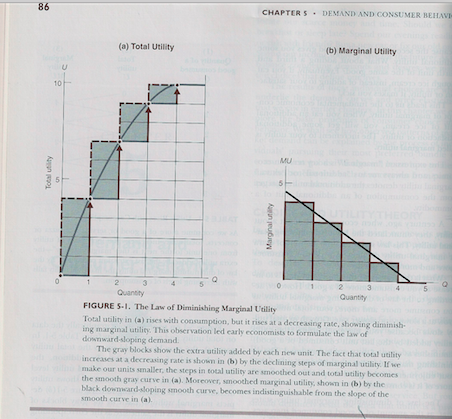

Jevons repeatedly uses language suitable to calculus to explain his derivation of economic laws. He refers to the effect of the increase in utility that comes from the addition of an “infinitesimal” increase in the amount of the commodity consumed; the use of that term, which could not possibly arise in the real world, is intended to make it appear that standard integration rules are applicable to his theory, and he draws smooth curves instead of stairstep lines to show the consumption of goods and services. Samuelson and Nordhaus do the same thing, though a bit more subtly. Economics, 2005 ed.

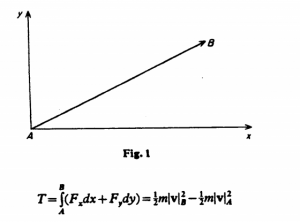

This is hardly the only inaccurate use of math. Consider this drawing from the Mirowski paper:

In this picture there is a point particle moved from point A to point B in a two-dimensional plane by a force F (vectors are usually indicated by bold-face; I’m also using italics). We can rewrite F as the combination of Fx and Fy the components of the force vector along the x and y axes. For a quick brush-up on this point, see this. The equation in the drawing gives the kinetic energy of the particle, denoted by T. If the expression Fxdx + Fydy is an exact differential, then there is another function U that meets this requirement:

![]()

The U in this equation is identified as the potential energy of the particle. The particle moves along a path such that the sum of T and U remains constant; usually this is written as T – U = 0. The point of Mirowski’s example is that we are looking at a force field, an energy field that describes the energy at each point by amount and direction. The function F does not have to be a simple equation as it would be in the first example; it can map out complicated curves. But F and each of its components have to be the exact differential of some other equation, which puts some constraints on them. Finally, we should note that this idea can be generalized to any number of dimensions.

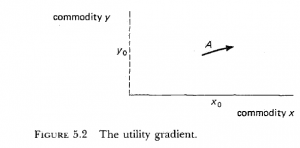

This is from the Mirowski paper:

Walras insisted that his … equations resembled those of the physical sciences in every respect. We may see now that he was very nearly correct. Simply redefine the variables of the earlier equations: let F be the vector of prices of a set of traded goods, and let q be the vector of the quantities of those goods purchased. The integral ∫F•dq = T is then defined as the total expenditure on those goods. If the expression to be integrated is an exact differential, then it is possible to define a scalar function of the goods x and y of the form U = U(x,y), which can then be interpreted as the “utilities of those goods. In exact parallel to the original concept of potential energy, these utilities are unobservable, and can only be inferred from theoretical linkage to other observable variables. P. 368

In other words, utility is a scientific construct. I hope this from the book will make this somewhat clearer.

Suppose we have a person with a supply of two goods that can be traded, designated by x0 and y0. The point A is the intersection of the two goods. In neoclassical economics world, our hypothetical person is presumed to know how much of each good the person would purchase with an infinitesimal increase in money. The person is presumed to know this for every point in the commodity plane. This example can also be expanded into multiple dimensions to cover multiple commodities.

The math goes on from here, but we don’t really need to follow it. We can see that this doesn’t really make good sense, the idea that we would know what to do with an infinitesimal part of a piece of money. But even the math doesn’t make sense, as Mirowski explains in tedious detail. The equations aren’t solvable unless there are certain kinds of constraints. The physics problem is solved by assuming that the energy of the system is conserved, or at least it was when Walras and Jevons were writing, and we still use that idea today for simple local problems, like mechanics in physics. But that constraint isn’t available in economics: T is the equivalent of money, and U is utility, and the two are measured in different units. The term T – U doesn’t mean anything. Neither do other possible constraints, as Mirowski explains. The math fails at every level, including the levels Mirowski plumbs and I won’t.

One of the problem this creates for economics is that it undermines the claim that markets are demonstrably a superior form of organization. Recall from this post that Jevons makes this claim explicit. There are other problems, as Mirowski explains in section 5 of the paper and at much greater length in the book.

The standard response to the deconstruction of the basis of the model is to say it doesn’t matter. The models work, so who cares how or why. This was Milton Friedman’s view, as in this excerpt from Essays From Positive Economics from 1953. This raises a host of fascinating questions, but for now, here are two thoughts.

1. Lots of important problems can be solved with simple Newtonian analysis. If I want to figure out how a ball will roll down a ramp or how the moon revolves around the earth, I don’t need anything more complicated to get really close to the correct answers. But there are many other problems for which relativity theory is necessary. There are others that cannot be solved without quantum mechanics. The fact that some kinds of economic problems can be solved with simple neoclassical models doesn’t mean that all economics works that way, or that there might not be other and much better ways to figure out how to organize a society for production and allocation of scarce resources.

2. Economics is not a normative field. The rules of a society must deal not only with economic efficiency and utility of individuals at a point in time, which seem to be the subjects of neoclassical market theory, but many and broader aspects of being human, including our interest in the future, the impacts of our behavior on other people, fairness, social justice, and a host of other concerns. The neoliberal program seeks to erase those concerns in search of homo economicus, the consuming person, as the sole exemplar and highest form of being human. When we talk about society, we are told by Margaret Thatcher that there is no such thing. Not only is there a society, there is a government, which is a tool for society to arrange things as we see fit. We don’t have to live like the solitary selfish solipsistic homo economicus. We have plenty of choices.

And thus you have part of the economics profession that gathers data that cannot be modeled to yield helpful insights into economic processes and the other part that creates models for which there is no data available to test.

Physics broadened its view as it became more complicated. Economic theory after sixty years still doesn’t know what to do with Wassily Leontief’s input-output tables or assess which econometric models are valid and which are flim-flams. Even as these models are put in computer systems that front-run all sorts of market behavior in order to gain competitive advantage.

Economics is normative in fact. It seeks to be the servant of patrons gaining competitive advantage — even at the cost of destruction of the economic system. One need only look at the catastrophe that the bankers have created in Europe to know that if these folks were actually using a phyics-engineering linkage as the simple-models suffice argument states, they would be fired for bridges that fall down. The fact that they are not fired says something about the economics profession and the also the way that economics of the “labor market” works.

Transactions, it appears are not transparent to their supply chains. Nor are they transparent to their value (utility) chains. Understanding the operation of a single digital switch is useful but it is not the same thing as understanding the components of a computer. The structure and function of economic institutions are what is left out. There are economic processes within firms, households, and governments that are nearly totally invisible. And these are where most of the issues are. For example, have you ever seen what happens with the CEOs of a firm get so free-market oriented that they try to establish internal markets to decide whether to build stuff inside the firm or contract it out? This is a constant temptation in contractor-manic management these days. Are not the results predictable without a whole lot of thought and are not the reasons easily modelable?

What if the fundamental economic process was not markets but one-to-one haggling? And that there is more going on that cost-utility calculation. Here’s a behavioral economics question. Why exactly is it that supposedly savvy CEOs will leave trillions of dollars on the table as cash instead of investing in new sorts of plant and equipment and workplaces, paying their taxes (or even paying more than their fair share for infrastructure), and hiring and training the workers that productively create goods and services and…be the customers for the new things that are produced? Why is it that these savvy CEOs run from one asset bubble to the next, always in paper and never becoming bricks and mortar? What exactly is their set of utilities and why does it exclude so many other people? And what science is appropriate to investigating and answering those questions?

Coincidentally I am reading a New Yorker article now also, about inequality. Her’s a similar quote from it, about the lack of ‘utility’ of numbers at times.

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/03/16/richer-and-poorer

Some people make arguments by telling stories; other people make arguments by counting things. Charles Dickens was a story man. In “Hard Times” (1854), a novel written when statistics was on the rise, Dickens’s villain, Thomas Gradgrind, was a numbers man, “a man of facts and calculations,” who named one of his sons Adam Smith and another Malthus. “With a rule and a pair of scales, and the multiplication table always in his pocket, Sir, ready to weigh and measure any parcel of human nature, and tell you exactly what it comes to.”

Numbers men are remote and cold of heart, Dickens thought. But, of course, the appeal of numbers lies in their remoteness and coldness. Numbers depersonalize; that remains one of their chief claims to authority, and to a different explanatory force than can be found in, say, a poem. “Quantification is a technology of distance,” as the historian of science Theodore Porter has pointed out. “Reliance on numbers and quantitative manipulation minimizes the need for intimate knowledge and personal trust.” It’s difficult to understand something like income inequality across large populations and to communicate your understanding of it across vast distances without counting. But quantification’s lack of intimacy is also its weakness; it represents not only a gain but also a loss of knowledge.

quote”We don’t have to live like the solitary selfish solipsistic homo economicus. We have plenty of choices.”unquote

I’m positive the Ghosts of Tom Joad are rolling on the floor in raucous gut splitting laughter.

Physics is not where economics belongs or ever belonged; certainly not when the psuedo-similarities of physics and the decision-making/”utility”/market-clearing portions of the new human intellectual adventure which came to be called “economics” were being formed.

Were one to use any area of physics for “concept modeling” it would be the similarly historically new area of quantum mechanics for the reason that the economic market-clearing activity of every actor is “recursive”, i.e., effects the behavior of every other actor.

the mathematical tools applied so successfully to quantum mechanics had to be invented due to the inseparablility of the individual actors, i.e., those mathematical tools were group (statistical) in nature, not individual.

Physics envy.

The models work, eh, so who cares about people and the economy they are meant to describe? Routine Friedmanite argument intended to obfuscate the political purposes of an effort designed ostensibly to remove the politics from political economy. If economics is a system of laws, and not based on the choices of people, no one can challenge the choices, point out their consequences, and demand better ones. An order of magnitude more subtle than Social Darwinism, another pseudo-scientific attempt to justify ruthless excess and social brutality. One might say of neoliberalism, all else is commentary.

I think the points from the previous post about different cultures and economic levels being represented by the one thing, “utility,” are more fundamental than this one. If utility is not an integrable function you can’t represent it by any other integrable function like a normal distribution. But I don’t know from this post how much of the macro models based on individual utility can be saved just by using different mathematical methods.

No, I didn’t look up Douglass North yet. Completely forgot.

Mathematical modeling could apply if researchers were clear what it is that they are modeling. An aggregation of haggling transactions is a pretty gaseous model, when it is pretty well acknowledged in business practice that economic transactions are piped through supply chains and value chains (whatever the heck that actually means). And that most business that engage in counting count things related to those concepts. Unlike physics and bridges, economics and business are really incommensurable in terms of each other. Part of the problem it seems to me is that economics insists on an essentially non-structural (non-institutional) model (folks like Coase, North, etc. excepted) and models economic activity with the law of gases–volume, pressure at the macro level being aggregated randomly without structure. But the modern corporation and modern economies are very tightly structured and rationalized.

There are complex models at both the macro and micro levels. Krugman has his IS/LM and econometric models and Wall Street have their derivative, EVA and Six Sigma models. Back before the crash they both figured out that a bad crash could never happen again bc it was all in the model to tell them what to do and when. Turns out they missed something, like greed and fraud and who knows, maybe something else. So from now on we are all smarter, right?

Suppose the models are based on the ideas about utility that economists take from Jevons and Marshall, who I didn’t mention. If those ideas are subject to the flaws I have been discussing, then the models have the same limitations, don’t you think? Is they some way the models account for the math and conceptual errors in this and other posts?

Ed, I wish I knew how valid these models were. But I think we have seen they have flaws, like witness the recent crash. I doubt economic behavior is always universal and so no model captures it all. On a macro level I trust the MMT and post Keynesian people. They seem to at least recognize there is more than one sector in the economy and interest rates may not control all economic activity, as opposed to the so called new Keynesians like Krugman. During my working years we dealt with simple modeling like EVA and six sigma. But the bosses were really interested in only how much cost they could extract from the process – read people — and not the goodness of the process. So I think models have limitations, and some – not all – of that is the way people use the model.

*

I have a very simplistic view of most of this and that is that the federal government has a vast array of resource to deal with most of our problems (though not all). It is unfortunate they are prevented by ignorance and politics from using it for the public purpose.

On the federal government being prevented by ignorance and politics from using its modeling capabilities for the public purpose, it is indeed almost like putting the ferrymen and livery stable operators in charge of designing roads and bridges.

My background is diverse enough (squirrely enough) to have seen modeiing from a variety of applications and perspectives. And economic models seem stuck in social statics to me. But that’s without having gone at any depth into econometrics.

Kenneth Arrow was writing about an interesting approach to models a couple of decades ago when he has just dealt with some economics of information stuff. There was another economist doing something with the economics of teams around the same time. Arrow’s model was one of agency. It seemed to be inspired by the node-communications link structure of the internet (although I do not know that that was its inspiration). The paper he did dealt with a simple model of an agent with certain behavioral assumptions.

It has occurred to me since that the the behavioral aspects of the agent is what microeconomics is about and that the geometrical properties of the connectional network among agents is what macroeconomics is about. Instead of an aggregate gas model (which Jevons seems to be trying to reach), it is a communications and transport network model (which is also closer to the actual reality). There are various kinds of agents, messages, commodities, subsystem rules in which networks of agents function as a single agent, and the fundamental geometry of an essentially closed system. That is, unless there is a way to conceptually extend the model to include various kinds of externalities, such as the inputs from the environment (the free lunch) and the inputs from society (the other free lunch) and the outputs back to externalities (the tax exerted by the environment and society). There is, IMO too quick a jump to the mathematical relationships in the process of the economy and too little modeling of the entitites actually involved in a way that can produce the data to inform the validity of models.

As you point out, a lot of that failure is a feature, not a bug. Movers and shakers don’t want investigators and modelers getting into their business. Because then we would either have true competitive markets with EVA approaching zero because all of the possible true efficiencies have be wrung out or we would see clearly the evasions of the competitive market that are going on.

IMO, what the models missed in 2008 was the operation of credit default swaps as a Ponzi scheme (especially in the “naked” credit default swap third-party contracts). And that had the effect of providing the base to leverage in creating what appeared to be huge profits but were in reality funny money to the tune at maximum exposure of $100 trillion in possible obligations if enough stuff was worthless. The bailouts rewarded enough but not all of the players to roll back in that exposure. I don’t think anyone had enough visibility into the credit default swap contracts and understood the fraud going on in the packaging of mortgage investments to model that sort of chicanery before the fact.

Which brings up one of the simplifying assumptions of modeling: the market punishes bad actors sufficiently to deter their bad actions. Simplifying because modeling it explicitly requires complicating the model with all of the major forms of bad action.

Yes. And it has been said housing was in a bubble that was due to break like the dot com bubble only bigger. Add that to outright fraud and very risky derivatives bets and the deed was done. I only wish we had used the opportunity to reorganize the largest banks and break them in pieces so it would take years to cause it again. But now we already know that Citibank has written their own derivatives law, and those investments are growing once again. Where were Krugmans models to help avert all this pain?

While I agree that economics is based on the logic and math of physics, it is not necessary to suppose a preference or utility function to generate the same economic results. Nobel Prize winner Gary Backer showed this in 1962 in his article entitled “The Theory of the Irrational Consumer”. He shows that if people shop and consume with no preferences beyond consume what is produced, on average, they will behave rationally. http://mcadams.posc.mu.edu/econ/Becker,%2520Irrational%2520Behavior.pdf

This is as fundamental as economics gets. The other question is that of rationality. After 4 years in a economics PhD program, the best definition of rationality I devised is that “rationality is the application of specific mathematical constraints necessary for economic models to produce stable, reproducable outcomes.” In other words, rationality constraints are required for the math to work.

The specific mathematical constraints are elegantly laid out in Hal Varian’s (UMichigan) book Microeconomic Analysis. http://www.amazon.com/Microeconomic-Analysis-Third-Edition-Varian/dp/0393957357

The title of Varian’s book refers to the mathematical field of study “Real Analysis” and has less to do with choice theory than the application of math to choice theory. The requirements for the math to work are:

Completeness – for all x,y in X either x≥y or y≥x or both.

Reflexivity – for all x in x, x≥x

Transitivity – for all X, Y and Z in X, if x≥y, y≥x, the x≥z.

Continuity – for all y in x {x: x≥y} and { {x: x≤y} are closed sets. It follows that {{X: x>y} and {X: xy

Local nonsatiation – given any X in X and any E > 0, then there is some bundle Y in X with | X – Y | X.

Strict convexity – given x≠y and z in x, if x ≥ z and y ≥ z, then tx = (1-t)y > z for all 0 < t < 1.

I doubt that anyone who is mathematically or logically adept will find these concepts troubling. Taken together they are constued to mean:

1. The economic agent is free to make decisions in what s/he perceives to be the individual's own best interests.

2. More is always preferred to less.

3. There are not sustainable cases of increasing benefit from consumption or production.

4. Rules of transitivity hold (if A is preferred to B and B is preferred to C, A will always be preferred to C).

But this is not what they actually mean. There is no consumer here maximizing utility. It says consumer behavior is rational if it is smooth, continuous, bounded, intransitive, and monotonic. That is a far cry from free choice.

Choice actually throws the model way off. The medically-certified paranoid schizophrenic Nobel Prize Winner and Beautiful Mind protagonist John Nash mathematically such human actions such as altruism — because the math is too hard. Even Nash's experiments showed women tended to be "irrational" because they would not act in their self-interest in certain circumstances.

While I left academic economics years ago, the problem of ever increasing difficult math plagued economics as a prescriptive social science. Gary Becker, in his seminal book "A Theory of the Family", included a chapter on altruism, but very little additional research has been done (probably due to a lack of grant funding).

Currently the field of economics is in a state of crisis on par with that raging in physics where an observer is required for physical reality to exist. Next time you see an economist, ask the question "what is the meaning of long term negative real interest rates?" [The purest answer is that people care more about the future than the present.] You can watch thier heads explode. Yet negative interest rates are readily observable in the world today. So what gives?

Thanks for that Becker paper. I assumed there must be something like this, because it certainly is true that the demand curves for specific items slope downward a good bit of the time, though not always, and the cases where they don’t are usually interesting. I’ll read the paper closely later.

Still, my point remains. Utility is the basis for the teaching of Econ 101, if Samuelson and Nordhaus are an indicator. The two ideas that people act rationally in the normal sense of that word, and that they pursue their personal utility, are basic to neoliberalism. Taken together, these paint a one-dimensional and static view of human beings.

The point of this series of posts is that academic economists teach the best and brightest students, the people who eventually run the country; and that insures that policy elites use that neoliberal discourse when they have power, regardless of their purported party affiliation. My argument is that this discourse is reductive and intellectually fraudulent.

Rationality is that which can be related and measured. Irrational is what DFHs and founders of religions see on self-induced vision quests. Here is a link to a good BBC video on the science of rationality. It is a documentary called FUCK YOU BUDDY by the BBC filmmaker Adam Curtis. It was shown with that title on BBC. It is worth the watch if you want to understand Political Economy.

http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x1zucf8_bbc-the-trap-what-happened-to-our-dreams-of-freedom-1-of-3-f-you-buddy_tv