CDC Modeling Demonstrates Importance of Intervention in Ebola Outbreak

Helpful graphic from WHO illustrating precautions to prevent infection while traveling. Click on image to see a larger version.

As the Ebola outbreak in West Africa continues to grow, fresh attention was focused on it yesterday when the CDC announced that in a mathematical model they developed of the outbreak, failing to intervene in spread of the virus could lead to as many as 1.4 million people infected by late January. Somewhat lost in the response to the “wow factor” of a projection of over a million people being infected is that the model also very powerfully demonstrates how the viral outbreak can be contained simply through moderate adoption of the most basic aspects of an infection control program.

First, to review from my previous Ebola post, Ebola is only transmitted when bodily fluids of infected or dead individuals come into contact with broken skin or mucous membranes.

The key to preventing spread of the virus is for those who care for infected patients, whether they are health care workers at a hospital or family members in the home, is preventing contact with fluids from the patient. CDC has prepared an informative guidance document for how health care workers can control the spread of Ebola in their facilities. The key steps are to provide protective clothing to cleaning staff, use an effective disinfectant, avoid re-use of materials with pourous surfaces and dispose (as regulated medical waste) of all textiles, linens, pillows and mattresses that may be contaminated.

Because practices such as these are routinely implemented in US health facilities when patients with high risk infectious diseases are being treated, there is little to no chance of Ebola spreading within the US. As noted in the previous Ebola post, the extreme poverty of the health care systems in the affected countries in Africa is what has allowed the disease to spread, as health care facilities there simply cannot afford the materials they need for implementing safe practices.

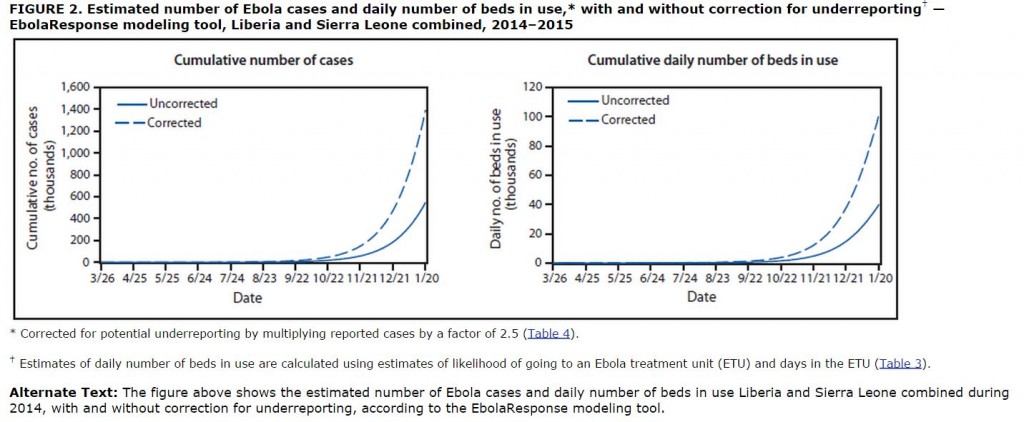

Here is the output of the model for Ebola spread in Liberia and Sierra Leone if infection control is not implemented beyond the current level. As noted in the NYTimes article linked above, the current estimate is that 18% of patients in Liberia and 40% of patients in Sierra Leone are treated in facilities that prevent spread of the virus. The model predicts both the number of infected patients in the two countries and the number of beds devoted to care of those patients (“corrected” means that the estimate for number of infected individuals is corrected for the assumption that 2.5 times more patients are infected than have been officially reported):

As noted above and widely cited in the press yesterday, if the virus outbreak is left unchecked, the model predicts a cumulative total 1.4 million infected patients in the two countries by January 20 (many of whom are dead by then) and a need for up to 100,000 beds for treatment of these patients.

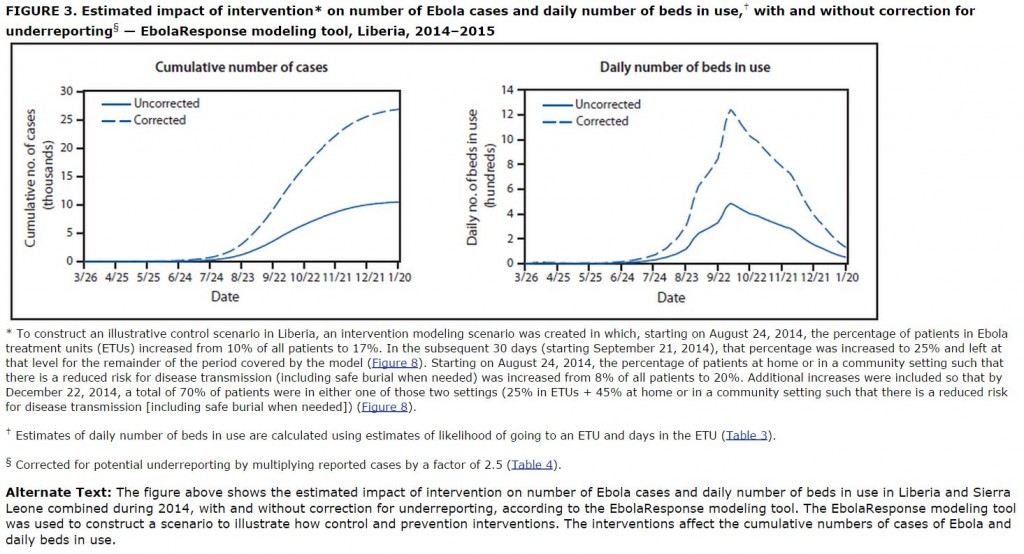

The good news that is buried in the CDC model is that stopping the virus outbreak does not require implementation of virus control measures for treatment of every infected patient. In the graphs below, we see the output from the model under the assumption that viral control practices start to be implemented now and expand to a level of 70% of infected patients (25% of them in hospitals and 45% in home treatment) being treated under safe practices by December:

Note that the cumulative number of cases levels off between 25,000 and 30,000 and the total number of beds needed peaks at around 13,000 1300 before dropping rapidly.

This model demonstrates very clearly that the highest priority for stopping the Ebola outbreak should be rapid and widespread implementation of basic infection control practices. Spreading this information into homes where patients are being treated is key. Convincing families of the importance of removing infected clothing and bedding seems likely to be the pivotal aspect of the public information campaign. Help from the West will be essential in providing the huge amount of disposable protective clothing and the necessary cleaning and disinfecting supplies. Replacement clothing, linens, mattresses and pillows should be provided as many of the affected families will be hard-pressed to replace these items under the already difficult conditions of an infected family member.

Further good news is that these projections were based on conditions in August and there is reason to believe that the situation may already be getting better. From the Times, again:

The caseload projections are based on data from August, but Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, the C.D.C. director, said the situation appeared to have improved since then because more aid had begun to reach the region.

“My gut feeling is, the actions we’re taking now are going to make that worst-case scenario not come to pass,” Dr. Frieden said in a telephone interview. “But it’s important to understand that it could happen.”

Let’s hope that Dr. Frieden is correct.

You’re quite correct across the board about the good results which can obtain if the sensible, science-based suggestions CDC makes are followed. But, in addition to the system failures existing in West Africa and cited in your piece – e.g., lack of adequate protective clothing, non-disposal of infected materials, etc. – there are two more impediments to containing this epidemic. Both of these will likely make efforts to contain the epidemic far more difficult if not impossible.

.

First, there is widespread ignorance and superstition about the outbreak, causing both fear and panic in the populace. This is exacerbated by various people (most probably unaffiliated with governments or organizations) spreading fear and mis- or disinformation. It’s the analog of someone here saying in the media that “science says global warming is real and here’s the science” (to pick one topic) and someone else denying the reality, basing their opposition on superstitious belief or fiction or propaganda.

.

The end result, of course, is confusion and the populace putting hard scientific information into the same boxes – marked “disbelieve” or “can’t tell which is true, so we argue about it” – as the dis- or misinformation.

.

Second, there has developed a substantial enmity in the populace to the very health teams coming in to provide hard, good information. There have been health care workers killed. This enmity develops out of the panic and confusion and acceptance, among some sections, of the rumor that the health teams are spreading Ebola, not trying to educate. Or that the education they provide actually facilitates the spread of Ebola. A further contributor is the very dis- or misinformation discussed above, which gives those who choose, for whatever reason, to not believe the good information, as debating point from which they can build their cloud castles.

.

It would be entertaining, in the way Republican Climate Change Deniers’ arguments are, were people not dying as a result.

.

So, it’s my prediction this epidemic will be much worse before it gets better. And I’ll also predict that the casualties will approach, if not exceed, whatever worst case estimate CDC gave.

.

People as individuals can be pretty smart. In groups, not so much. And they can and do panic entirely too easily.

.

The trends you describe are part of why I was so excited about the model predicting only 70% compliance with safe practices being necessary for the intervention to work. Whether we are talking about the hard core wingnuts who were still supporting W at the end of his days or the crazies you describe in Africa, it seems that around 30% of any population chooses to promote stupidity, often in very dangerous ways.

.

The real battle will be whether the crazies in Africa are able to prevail in preventing the education that is needed to get most families to implement safe practices. Getting to 70% somehow seems achievable to me. If it required 85 or 90%, I’d be really worried about huge swathes of the population being wiped out in West Africa.

.

One other routine that will be difficult to confront is that in some of the affected areas, burial practices can contribute to spread of the virus, and changing long-held cultural practices at stressful times is likely to be difficult.

It is certainly right that basic infection control practices are the basis for controlling the spread of Ebola.

.

However, none of the projections address the evolution of the Ebola virus. Viruses often mutate and evolve in proportion to the number of infections. We are already into tens of thousands of infections, heading towards hundreds of thousands at a minimum. There is evidence of Ebola spread via aerosols in animals, not direct contact. Widespread evolution of that, or other infection modes, in humans would change the projections profoundly.

.

Is there “good news” as you note, or might it more rationally be “bad news”? The “good news” projections of numbers of infections make Ebola evolution likely. It is a roll of the dice on what that evolution will bring.

.

Rosy projections that fail to account for evolution may turn out to be literally “whistling past the graveyard”.

.

It’s far less dangerous, in those terms, than flu.

The difference is that Ebola mortality is profoundly higher than with flu, except H5N1. The fear with that, as with Ebola, is that it will evolve to spread via aerosols.

.

If you haven’t read it, “The Hot Zone” is sobering, and a true story about viral evolution and spread in the D.C area. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Hot_Zone

We have been lucky so far. Today’s Wash Post reports:

.

“Only a fluke of timing prevented Kent Brantly from being in Texas when he got sick with Ebola.

.

Brantly, the first U.S. doctor to get Ebola, was infected in late July while working at a missionary hospital in Liberia. But he didn’t immediately realize he was ill. That’s one of Ebola’s tricks: The virus can take three weeks to appear, although severe signs usually strike within 10 days. Still, that’s time enough for someone to jump on a plane and fly around the world.

.

So Brantly was already infected with Ebola but not yet sick — and thus not yet contagious — when, on July 20, his wife and children flew from Liberia to Texas for a wedding. The doctor was scheduled to meet them in Texas a week later. He never made that flight. He fell sick three days later. An Ebola diagnosis followed. He soon made a high-security medical evacuation to Emory University Hospital in Atlanta where he eventually recovered.”

.

While I am not inclined to jump on board ‘worst case scenario’ bandwagons, I question this claim:

First, to review from my previous Ebola post, Ebola is only transmitted when bodily fluids of infected or dead individuals come into contact with broken skin or mucous membranes.

It is nearly inconceivable to me that there could have been such a huge uptick in the numbers of health professionals contracting the disease if it hadn’t mutated beyond that stage. In other words, it is difficult to believe that it hasn’t, at least to some degree, aerosolized. If this is not the case, I would appreciate hearing an alternative explanation for the sudden explosion in the number of health care workers who have contracted the disease.

.

Go to that earlier post and read the article linked there by Laurie Garrett. It is clear that the countries experiencing the outbreak are unable to fund their health care system with even the most basic materials needed for health care professionals to protect themselves from infection. She lays out the case quite clearly and convincingly.

“World-class health care”, as in “the level of health care the vast majority of the world’s population enjoys”, works out to be a couple dirty needles and a bunch of old rags for bandages, in an open-to-the-air building, with maybe (if they’re lucky) a mosquito net with only a couple holes in it. Maybe some rubbing alcohol or something akin to Lysol, sparsely used because there isn’t more available.

.

Basic infection control is pretty difficult in that context. Basic cleanliness is. Let’s not even think about the kind of gloves, splash and spit guards available in most dentist’s offices in the US, nor the face shields and moon suits most people think necessary when it comes to agents like Ebola. The countries experiencing this outbreak can only dream of that.

Wait a second. I’m referring to Western health care workers, so the various countries’ facilities are not the issue. I believe that it is extremely misleading to suggest that Ebola has not, at least to some degree, become aerosolized.

Here is a quote from CIDRAP “by the authors, who are national experts on respiratory protection and infectious disease transmission”:

We believe there is scientific and epidemiologic evidence that Ebola virus has the potential to be transmitted via infectious aerosol particles both near and at a distance from infected patients, which means that healthcare workers should be wearing respirators, not facemasks.1

The minimum level of protection in high-risk settings should be a respirator with an assigned protection factor greater than 10. A powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR) with a hood or helmet offers many advantages over an N95 filtering facepiece or similar respirator, being more protective, comfortable, and cost-effective in the long run.

“…the total number of beds needed peaks at around 13,000 before dropping rapidly.”

The lower chart of number of beds in use has a different Y-axis label of hundreds, so the peak shown is actually at 1300.

.

Oops. Thanks for catching that. I’ve put a correction in the text.