New Email Release Shows: Peter King Demanded an Investigation To Find Journalist’s Sources Like Peter King

On May 7, 2012, then Associated Press reporters Adam Goldman and Matt Apuzzo broke the story of a thwarted al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) underwear bomb plot. Within a day, several news outlets — including ABC News, Los Angeles Times, and New York Times — reported that the culprit was actually a Saudi agent.

On May 9, 2012, Representative Peter King called for an FBI investigation to determine who leaked details of the plot to the AP.

I’m calling on the FBI to do a full of investigation of how this was leaked, who’s leaking it. And also the CIA to do an internal investigation.

[snip]

This came from such a small circle. Nobody in Congress knew about it. My understanding is very few of anyone in the FBI even knew about it. And yet so much of it was leaked to the Associated Press a week ago, and now someone’s leaking like a sieve. This is really dangerous to the national security.

DOJ did launch the investigation King demanded. In fact, in early 2013, DOJ obtained the phone records of 20 AP phone lines — affecting 100 AP journalists — without giving the outlet an opportunity to challenge the subpoena. The investigation and excessive subpoena has marked one of the low points of the Obama Administration’s crackdown on journalism.

The investigation ended last September when former FBI bomb expert Donald Sachtleben pled guilty to serving as a source to one of the AP journalists. Prosecution documents revealed that, because the government had already been investigating Sachtleben for child porn charges, they already had the means to find his communications with the AP reporters, without compromising the sources of 98 other journalists.

The investigation King demanded ended up needlessly compromising the reporting of a slew of journalists.

That’s remarkable, because — as emails newly released by The Intercept‘s Ken Silverstein show — Peter King himself was talking to journalists about the story.

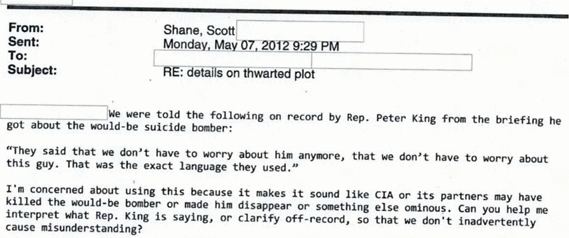

Within hours of the first AP report, Scott Shane, of the New York Times, emailed CIA’s press office asking them to clarify something King told the NYT, based on the briefings King had gotten about the plot. “‘They said that we don’t have to worry about him anymore, that we don’t have to worry about this guy. That was the exact language they used,’” Shane recounted King explaining, on the record. “Can you help me interpret what Rep. King is saying…?”

As King explained to Wolf Blitzer two days after this conversation with NYT journalists — even as he was calling for an investigation into the the people leaking classified information — he had been in a number of Top Secret briefings on the plot. King complained that “so many people are talking about something which is still classified.”

Representative King’s office did not return a request for comment.

Shane explained to ExposeFacts over the weekend that King’s comment led him to wonder whether — and then confirm — the bombing culprit was really an infiltrator. “I do remember being genuinely puzzled on May 7 by King’s remark that he had been told we ‘don’t have to worry about’ the guy and trying hard that night to get officials to clarify,” Shane described. “The next morning it suddenly occurred to me that the guy might have been an agent,” he continued. “I finally got someone to confirm in the afternoon and we posted a story.”

On May 8 — even before King started calling for an investigation into those leaking classified information — Shane and Eric Schmitt reported, “The suicide bomber dispatched by the Yemen branch of Al Qaeda last month to blow up a United States-bound airliner was actually an intelligence agent for Saudi Arabia who infiltrated the terrorist group and volunteered for the mission, American and foreign officials said Tuesday.”

Shane emphasized that he doesn’t know whether King meant to imply that the culprit was an infiltrator. “I actually have no idea whether King himself at that point knew the guy was a double agent — that was so sensitive that they may have omitted it from his briefing.” But by sharing details from the briefings he had gotten, King provided a clue that led the NYT to learn and report an important new detail about the plot.

That’s not to say Peter King should be investigated for leaking to journalists — as he himself insisted should happen — or lose his access to classified information on the House Intelligence Committee. On the contrary, it’s a good example of how journalists work — and should work.

On the contrary, it shows why the first response to solid national security reporting should not be to demand an investigation. Even an innocuous comment may lead journalists to ask the right questions to flesh out the story. Those kinds of conversations should not be criminalized … even in spite of what King demanded.