SIGAR Finds That ANSF Weapons SCIP Away from OVERLORD

I have been harping lately on the US approach to international crises being to first ask “Which group should we arm?” and how this strategy has come back countless times to bite us in the ass, as seen most spectacularly in Osama bin Laden. Further, in Afghanistan, the dual problems of failed training and insider attacks have demonstrated that Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) are ineffective and now even require a separate layer of security between them and US forces.

Back when there was a stronger push for the US to arm and train “moderates” in Syria, I noted the poor record-keeping that was being put into place, where we were being assured by those doing the training that they were getting handwritten receipts for the weapons they were handing out. Who could have known that in our much larger program of handing out weapons, in Afghanistan, that records were not much better? The 2010 NDAA required that DOD establish a program for accounting for weapons handed out in Afghanistan. The Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction released a report today (pdf) on how that accounting has gone. And the answer is not pretty:

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2010 required that DOD establish a program for registering and monitoring the use of weapons transferred to the ANSF. However, controls over the accountability of small arms provided to the ANSF are insufficient both before and after the weapons are transferred. Accountability over these weapons within DOD prior to their transfer to Afghan ownership is affected by incompatible inventory systems that have missing serial numbers, inaccurate shipping and receiving dates, and duplicate records, that may result in missing weapons prior to transfer to the ANSF. However, the problems are far more severe after the weapons are transferred to the ANSF. ANSF record-keeping and inventory processes are poor and, in many cases, we were unable to conduct even basic inventory testing at the ANSF facilities we visited. Although CSTC-A has established end use monitoring procedures, the lack of adherence to these procedures, along with the lack of reliable weapons inventories, limits monitoring of weapons under Afghan control and reduces the ability to identify missing and unaccounted for weapons that could be used by insurgents to harm U.S., coalition, and ANSF personnel.

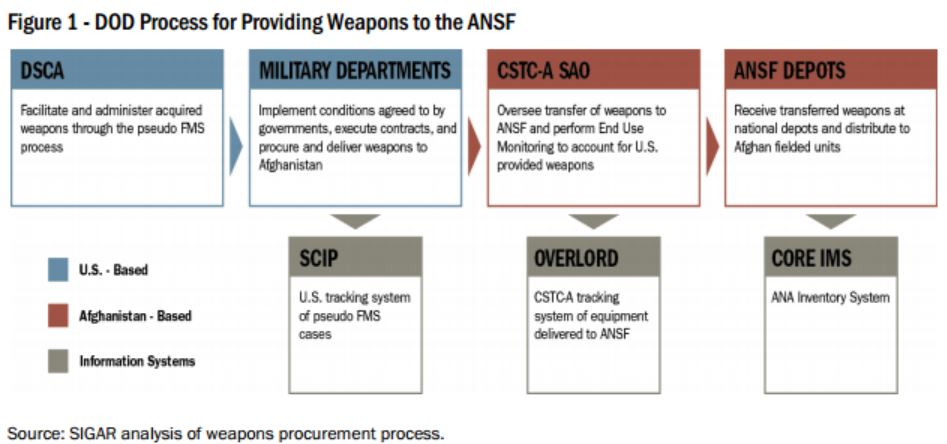

This graphic from the report shows the insanity of how three completely independent and incompatible databases are used to track the weapons:

Seriously, who comes up with these acronyms? The database used by the military in shipping the weapons out is the Security Cooperation Information Portal, or SCIP. This name seems designed to let us know up front that these weapons are skipping town and there is no prospect for tracking them. And to make sure they can’t be tracked, once they arrive in Afghanistan, the weapons are logged in, but they go into a completely different database incompatible with SCIP. In Afghanistan they use the Operational Verification of Reliable Logistics Oversight Database, or OVERLORD. SIGAR tells us “SCIP is used by DOD personnel to track the shipment of weapons from the United States, while OVERLORD is used for tracking the receipt of weapons in Afghanistan. Errors and discrepancies often occur because these two systems are not linked to each other and require manual data entry.”

Perhaps if we were dealing with the relatively smaller number of weapons for an operation like our death squad training in Syria, manual entry into a database might make sense. But here is a photo from SIGAR of one of the weapons caches that they attempted to audit in Afghanistan:

But perhaps even worse is that SIGAR has found Afghan forces already have far more light weapons than they need. From the databases they determined that there are 112,909 weapons in excess of stated needs for the Afghans (and 83,184 of them are AK-47’s that many Afghans learn to handle practically from birth) already in country.

As if that is not enough, more weapons will keep flowing even though ANSF force size is projected to shrink:

The problems posed by the lack of a fully functional weapons registration and monitoring program may increase as plans to reduce the total number of ANSF personnel proceed. According to our analysis, the ANSF already has over 112,000 weapons that exceed its current requirements. The scheduled reduction in ANSF personnel to 228,500 by 2017 is likely to result in an even greater number of excess weapons. Yet, DOD continues to provide ANSF with weapons based on the ANSF force strength of 352,000 and has no plans to stop providing weapons to the ANSF. Given the Afghan government’s limited ability to account for or properly dispose of these weapons, there is a real potential for these weapons to fall into the hands of insurgents, which will pose additional risks to U.S. personnel, the ANSF, and Afghan civilians.

What could possibly go wrong?