“Trap and Trace Confidentiality” and National Dragnets

As a number of outlets are reporting, ACLU liberated some emails catching Florida cops agreeing to lie about the Stingray devices used to capture suspects.

As you are aware for some time now, the US Marshalls and I believe FDLE have had equipment which enables law enforcement to ping a suspects cell phone and pin point his/her exact location in an effort to apprehend suspects involved in serious crimes. In the past, and at the request of the U.S. Marshalls, the investigative means utilized to locate the suspect have not been revealed so that we may continue to utilize this technology without the knowledge of the criminal element. In reports or depositions we simply refer to the assistance as “received information from a confidential source regarding the location of the suspect.” To date this has not been challenged, since it is not an integral part of the actual crime that occurred.

The email goes on to instruct that “it is unnecessary to provide investigative means to anyone outside of law enforcement.”

But i’m most interested in the subject line for this email: “Trap and Trace Confidentiality.”

That seems to confirm what ACLU and WSJ have reported earlier this month. Law enforcement are obtaining location data under Pen Register or Trap and Trace orders, meaning they’re claiming that location data are simply metadata.

That (and the arrogant parallel construction) is problematic for a lot of reasons, but given two developments on the national dragnet, I think we should be newly concerned there, too.

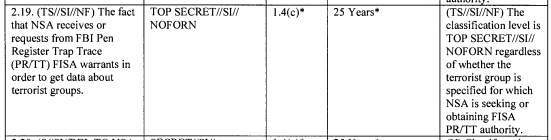

As I have noted, several months after NSA’s Pen Register/Trap and Trace authority was shut down, FBI still had an active PRTT program from which NSA was obtaining data.

And not only does it seem that the government plans to resume some kind of PRTT dragnet, but there’s reason to believe they’re still hiding one.

The thing is, I have perhaps mistakenly always assumed these PRTT programs involved the collection of Internet metadata off telecom backbones. While I’m sure they collect large amounts of Internet metadata somehow, I realize now that they might also be operating (or planning to operate) large scale PRTT location programs. Remember, too, that Ron Wyden was asking provocative questions about the intelligence community’s use of cell location data just days before this classification guide.

Mind you, the Quartavious decision might make that impossible now.

But given the USM apparently concerted effort to hide the fact that PRTT equates to cell location orders, we should at least consider whether the government operates more systematic location programs.

I don’t own a cell phone, The thought of law enforcement being able to track your location at any given moment is disturbing. Trap and traces in itself is disturbing. We have a trap and trace on our landline, according to our most current FBI files and it is sometimes unnerving as we do talk to family in other countries. Thank you Empty Wheel for opening up the conversation on a topic that should outrage everyone equally!

you can’t kill a hydra by negotiating for good behavior with a few of its heads.

of great interest to me is the role of the department of homeland security in encoraging use of warrantless geo-location devices (and an armory of weapons and equipment).

is there any reason to think this isn’t under the advice and control of the whitehouse? with legal support from the doj?

i just can not understand why any of this hyper-surveillance/spying/militarizing police is needed in this country. we do not face any pervasive internal threat other than automatic weapons and clips. the dhs armamentarium being distributed to local police is being used, actually mis-used, most frequently against americans who are little threat.

Caught lying? Who could have known?

This language appears to be a setup, “to ping a suspects cell phone and pin point his/her exact location in an effort to apprehend suspects involved in serious crimes,” designed to provide the most plausible rationale for this behavior. It is not a credible claim that this function is only used when LEO’s are attempting to make an arrest in connection with an already committed “serious crime”. It would be too tempting not to use it in connection with surveillance generally, before and after commission of a crime, whether of perps, proposed witnesses or others. And that ignores illegal personal use.

If the use, per ping, of this device is not registered, logged and retained, and it is not subject to discovery by internal or external investigators, inspectors general, and defense counsel, it will be abused. It’s the nature of the beast.

The 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals squarely held on June 11 “that cell site location information is within the subscriber’s reasonable expectation of privacy. The obtaining of that data without a warrant is a Fourth Amendment violation.” U.S. v. Davis, No. 12-12928 (11th Cir., June 11, 2014), pg. 23, http://www.ca11.uscourts.gov/opinions/ops/201212928.pdf

The court engaged in a very careful analysis of the Supreme Court’s split decision in U.S. v. Jones, 132 S. Ct. 945 (2012) on global positioning system location data to distinguish the much older Smith v. Maryland trap and trace decision, bringing the case to the sole question of whether the privacy — as opposed to trespass — approach to 4th Amendment searches and seizures initially embraced in Katz v. Maryland applied to cell phone location data. The Court held that the location data was sufficiently intrusive on a reasonable expectation of privacy to justify leaving Smith’s third party doctrine behind.

The question at this point is whether the Justice Dept. applies to the Supreme Court for a writ of certiorari in this case or decides to try its luck in another circuit first. I suspect that DoJ may take the latter tack because a majority of the justices in U.S. v. Jones were obviously signaling that they would like to decide such a case. And that was before the Snowden disclosures.

The 11th Circuit’s analysis tracks closely with that of Judge Leon in Klayman v. Obama, 957 F. Supp. 2d 1 (D. D.C. 2013) (NSA obtaining call metadata requires a judicial warrant based on probable cause) and more recently the opinion of Judge Haggerty in Oregon Prescription Drug Monitoring Program v. U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency, Civil No. 3:12-cv-02023-H (Slip Op., February 14, 2014) (DEA prohibited from obtaining prescription drug records from a state registry of Schedule 3 prescription records by administrative subpoena; 4th Amendment requires a judicial warrant based on probable cause). DoJ took no appeal from Judge Haggerty’s ruling, almost without doubt in part because the ACLU’s Nathan Wessler wrote such an epic winning brief.

Significantly, both Judges Leon and Haggerty rejected the Smith v. Maryland third party doctrine and, like the 11th Circuit, examined Smith v., Jones closely to impose the judicial warrant requirement.

In the post-Snowden disclosure era, the outlier so far — at least by my count — is Judge Pauley in ACLU v. Clapper, 959 F.Supp.2d 724 (S.D. N.Y. 2013). Judge Pauley seems to be the only judge regarding the Smith v. Maryland Third Party Doctrine as still viable in defending government surveillance of internet communications.

Nb., While not decided in that case, Judge Haggerty’s decision in Oregon probably also spells doom for the Patriot Act’s section 215, 50 U.S.C. 1861(a)(3), authorization for warrantless harvesting of individually-identifiable medical records.