How FISA Dockets (Appear To) Work and Why Snowden Likely Got Few or No PayPal Documents

Because Bill Binney made an observation about the high docket number of the phone dragnet order released this year, Sibel Edmonds has decided that Glenn Greenwald is hiding a bunch of Edward Snowden documents to protect Pierre Omidyar showing PayPal cooperated with NSA.

Here’s what Binney said, according to him.

Unfortunately, Sibel attributes some of her words to me. I do not know that PAYPAL is involved – only that financial data is being used by NSA. And, based on the “BR” number 13/80 on the Verizon court order to give records to NSA, I estimated that this program involved 78 companies. These would include: telecom’s, internet service providers, banks/finance/credit cards, travel, plus others. So, there’s a lot of business data being collected by NSA and the FBI. In the future, if I am to be quoted, I will have to I will have to insist on a pre-publication review. [my emphasis]

Now, like Peter Kofod, I don’t doubt that PayPal gives a ton of data to the national security state (more on what probably happens below).

But Binney’s comment appears to be based on a misunderstanding of how the FISA docket numbering works (though not one that changes his observation that “there’s a lot of business data being collected by NSA and the FBI”): that each docket pertains to a different company.

Given the filings we’ve seen from voluminous years — particularly 2009 — it is clear that DOJ uses one docket for all providers on a particular order. For example, 3 of the 4 docket numbers used for the phone dragnet in 2009 were 08-13, 09-06, and 09-13. For the entire 3 month period the primary order covers, all the orders and correspondence related to that primary order bears the original docket number. Even in the case where Judge Walton cut off and then resumed production (see 09-13 above) from just one provider got handled in that docketing system. The now public FISC docket appears to continue this practice, with BR 13-109 and BR 13-158 including all the correspondence on a particular order (in addition, there are the Misc dockets for lawsuits, and the 2007 docket tied to Protect America Act for the Yahoo challenge).

And over the years, the list of providers included on the dockets appears to have gotten much longer. Here’s the redacted list of providers from the original 2006 order:

Here’s the redacted list of providers from the most recent order:

The additional providers are probably smaller providers, as well as VOIP providers.

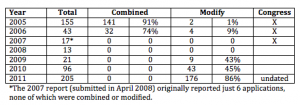

So just 4 and on rare occasions 5 of the Section 215 (“BR”) docket numbers in any given year (and, for the life of the program, just 4 of the PR/TT docket numbers) covered all the providers.

But that may, in fact, mean far more companies are getting Section 215 orders, even bulk orders. As I laid out in this post, the numbers of Section 215 orders have gone up in the last several years (Julian Sanchez has speculated that previously some of this collection was done via National Security Letter, which is a pretty good bet).

And as they’ve gone up, the FISA Court has been modifying far more orders — it modified 86% of the orders in 2011. It has been modifying orders to add minimization procedures (it modified 176 orders in 2011 to add minimization requirements). Given that you only need to have significant minimization procedures if you’re getting a lot of innocent people’s data, and given that these orders would also be on a 90-day cycle, that may mean there were 44 bulk collection programs in 2011.

But, as Binney said, that’s going to include a lot of different kinds of companies. We know they’ve used Section 215 to collect precursor chemical purchase records. They likely cover credit cards records, other financial records, gun purchases, health and medical records, and other computer records. There have even been questions about using Section 215 to collect URL search terms.

PayPal is one possible or even likely recipient of these, but only one out of a bunch. (Plus, it likely would have been receiving NSLs rather than Section 215 orders when Pierre Omidyar had more involvement.)

There are two other things to remember about PayPal’s dealings with the National Security State.

First, its primary, affirmative obligation would be to provide Treasury Department information on any of its customers who appear to be money laundering or doing something else funky with their accounts, as well as those transferring more than $10,000. Treasury has been reaching out increasingly to non-bank entities more in recent years, which probably has brought even more scrutiny on PayPal, but PayPal has a bank and it would have had the obligation anyway for years. This reporting would be done by a compliance department, and would be above board (that is, it is a known obligation banks have). This data likely gets crunched by both Treasury and, for a variety of different uses (counterterrorism, proliferation, drugs), ODNI. I don’t know whether it gets shared with NSA or whether that kind of analysis happens at ODNI.

Then there would be compliance with NSLs and 215 Orders. The thing is, NSA claims (for what that’s worth) to only be involved in the phone dragnet orders. If that’s true, other NSL/215 orders would come from FBI. And records of those orders are far less likely to be in the Snowden documents (I don’t think we’ve seen any FBI documents to date). So one explanation for why Glenn Greenwald hasn’t found any PayPal documents is that PayPal documents likely weren’t on NSA’s servers, they were likely on Treasury and FBI’s servers.

Finally, there is one way NSA might access PayPal information. For purposes for which Section 215 (which is limited to counterterrorism and counterintelligence purposes) and Section 702 (which I believe is limited to counterterrorism, counterproliferation, and cybersecurity purposes) are not available, NSA might well get data from upstream collection overseas. I honestly think that’d be the most likely way NSA’d be getting PayPal information. But in that situation, PayPal wouldn’t know about it. (NSA doesn’t generally tell companies when it steals from them.) So maybe Glenn does have a random PayPal document in his possession, but if he does, it’s likely that Omidyar didn’t know about it.

(Also note, we’ve heard of at least one major Internet company CEO who is not read into his or her company’s NSA programs.)

None of that says anything about how much data PayPal gives the National Security State (it would be obliged to give a good deal to Treasury in any case). But it does explain why it’s unlikely we’d see much of it.

Yes, exactly.

A couple points: First, and forgive me if you’ve already addressed this, what do you suppose are the chances someone at NSA had the means to tap into other agencies’ systems, including those at FBI or Treasury?

Second, one doesn’t have to agree Edmonds made a persuasive case to be left wondering about the cache Snowden gave to Greenwald & Poitras, and how it might empower whoever controls it to broker any number of deals, up to and including the extraction of tribute, in whatever form the latter might take.

Only days ago, Alan Rusbridger testified to Parliament that the Guardian had decided to not even look at those portions of the cache concerning Iraq or Afghanistan–obviously begging the question of how they’d know what not to read without having read it first. In any event, one can easily imagine folks on this side of the Atlantic taking comfort in Rusbridger’s words.

Rusbridger’s admission raises legitimate concerns that Pierre Omidyar, as Greenwald’s and Poitras’ newest employer, may have potentially positioned himself to parlay the cache into favors, whether to benefit him, those who want to do business with him, or those in the USG with whom he and his business partners would like to remain on friendly terms. Or to put it another way, whether Omidyar’s past or current business ventures are directly implicated by the cache may ultimately be beside the point.

Whatever the motives or capacities of the people involved, the analysis of the cache to date has played out in slow motion. It’s been six months since the Guardian’s first story, and in that time only a miniscule number of people have analyzed even a portion of the cache, resulting in publication of, at most, 1% of its contents. At this rate, it could be many years before we’d know the extent of the abuses described therein. Meanwhile, given Moore’s law–not to mention our moribund political process and its near total surrender to the National Security State–surveillance capacity will almost certainly continue to advance by leaps and bounds, far outrunning our ability to keep pace.

For these reasons, while I might not share Edmonds’ suggestion that she’s found a smoking gun, I think her general concern about potential conflicts of interest is entirely sound.

“Unfortunately, Sibel attributes some of her words to me. I do not know that PAYPAL is involved – only that financial data is being used by NSA. And, based on the ‘BR’ number 13/80 on the Verizon court order to give records to NSA, I estimated that this program involved 78 companies. These would include: telecom’s [ugh], internet service providers, banks/finance/credit cards, travel, plus others. So, there’s a lot of business data being collected by NSA and the FBI.”

EW emphasized the latter agency, perhaps out of a sense of satisfaction for having noted someone ELSE finally saying as much. And sadly, her intuition is entirely within the realm of possibility. I can remember a time not too long ago when NSLs fell from the sky like rain (i.e., with little or no outside, um, influence much less oversight), to the point where DHS, for example, would privately and self-righteously warn, believe it or not, a would-be DATE about you IRC if you happened to be enough of a smartass IRL (e.g., if you were lucky enough to have the mental wherewithal to be able to tell one of their douchebag provocateurs hired out of prison, tax-free, to go take a hike). That’s not a wildarsed guess. It’s a fact.

@spongebrain: Right. Real basic point about the Snowden documents people forget far too often: they’re only NSA documents. Therefore we’re not seeing a whole range of documents on spying.

@rsmatesic: Alternately, you could look at the issue you raise: that Guardian refused to consider publishing Iraq and Afghan documents, and come up with a totally different scenario, on which hews closer to the known evidence.

Guardian stalled on the Tor story. Guardian has said they wouldn’t publish Iraq/Afghan stories. We know Scahill and Greenwald were working on an NSA and drones story that has never been published.

And then Greenwald left and teamed up with a guy willing to pay a lot of money for legal talent.

That, to me, suggests there were limits on what he could publish at the Guardian and for whatever reason believes he’ll be able to publish more with Omidyar.

And remember, too, the real pressures on the Guardian. Not only British efforts to legally threaten the entity as a whole (which led the Guardian to bring in the NYT as cover), but a fairly precarious financial situation, in that its burning through its endowment, which at the very least makes it susceptible to financial and legal (which is another kind of financial) pressure.

Either one of course could be true, and it certainly makes sense to reserve judgment. But when people like Edmunds ignore a great deal of known evidence and instead invent claims that a basic understanding of the situation can refute, you gotta wonder everyone is assuming the most damning interpretation, and completely and utterly ignoring the evidence pointing to the opposite.

@emptywheel:

answers some worries and suspicions i have had about the guardian’s admirable but, i suspected, limited capacity for attack.

interesting about omidyar and legal talent. i have gone thru scenarios myself of ways to attack the rightwing domestic political machine and, other than critical or ridiculing anonymous youtube ads and or a weblog, the need for legal muscle is always there, i.e., critical teevee ads would most certainly be initially rejected and slap suits for other efforts can be counted on.

@rsmatesic:

but the documents re iraq and afghanistan are out there.

they will likely be published, at least historically, and they may be very important for pointing to political scheming between us and uk, for political decisions making such as that involving brit petro, and for evaluating bad military decisions, let alone torture, assassinations, and other small matters involving “sources and methods” and “tradecraft” (a pompous, silly phrase that has me gritting my teeth as i type it).

A mere footnote, but the deconstruction of FISA dockets numbers is a remarkable piece of citizen counterintelligence. Thanks, Marcy.

Excellent. Very glad that you wrote this.

Even though I read almost every post on this web site, I am always grateful for these rehash/summarization posts. I know that a lot of work goes into them and it must be difficult to take the time to do them when you’re trying to keep up with the warp speed of new information.

@joanneleon: Ditto

“Rusbridger’s admission raises legitimate concerns that Pierre Omidyar, as Greenwald’s and Poitras’ newest employer, may have potentially positioned himself to parlay the cache into favors, whether to benefit him, those who want to do business with him, or those in the USG”

I don’t get this. What about Barton Gellman? Or various Guardian reporters and editors? Or the NYT? Or Pro Publica? Or Snowden, who still communicates with the outside world, himself? How exactly are Greenwald and Omidyar supposed to conspire to do what you suggest?

@heliopause: First, the available information indicates no one outside of NSA and its private partners currently has more than the most superficial command of the majority of what Snowden exfiltrated, including Snowden himself. And this is true not only for the smaller portion of the cache that Gellman received, but for the larger portion Snowden gave to Greenwald and Poitras, as well.

Do the math: It is beyond human capacity for Snowden to have analyzed (or, in his own words, to have “carefully evaluated”) each of tens or hundreds of thousands of documents prior to turning them over to Gellman, Greenwald, and Poitras, despite Snowden’s and Greenwald’s claims to the contrary. It’s just as impossible that to date any of the latter, along with their respective associates, could have come close to fully comprehending the contents of a cache that according to NSA’s most recent estimate totals 200K documents. For a compelling dissection of the various claims regarding the volume-vetting issue, see here.

Second, you seem to have assumed NSA doesn’t have at least a general understanding of what Snowden exfiltrated, nor of the nature of the materials he passed on to Gellman, Greenwald, and Poitras. Apart from the declarations of the people involved, what convinces you this is so? Have you considered that some in government might actually perceive a benefit in hyping the unknown unknowns™ of Snowden’s leaks? And furthermore, what convinces you NSA–not to mention its private partners, and anyone else with reason to think they or their competitors might be implicated in the data–has no interest in retrieving or concealing the balance of a cache that, according to Greenwald, has been cloned only once, with both copies now potentially within Omidyar’s control?

If information is power, then whoever controls the information can manifest that power just as surely in the act of concealment as in disclosure. Is it really too far-fetched to assume persons other than journalists and a billionaire publisher or two might be very interested in controlling what portions of Snowden’s cache ever see the light of day? And when one considers that Omidyar has shown himself to be anything but the the poster child for transparency–apart from the elite-mediated variety (see here, here, here, and here)–as well as less than forthcoming about the role he and his business ventures played in the prosecution of the PayPal 14, I suggest at a minimum that we keep an open mind, and not dismiss what we can’t at this point disprove.