2012 Afghan Fighting Season Data Are In: Daniel Davis Was Right on Surge Failure

As the “fighting season” for the tenth full year of US forces being in Afghanistan comes to a close, the Defense Department has released its most recent report (pdf, required every Friedman Unit by law) on “progress” in the war. Although the military does its best, as always, to couch its report in language describing progress against goals which always must be redefined in order to claim any progress, those who have been paying attention knew from the report prepared early this year by Lt. Col. Daniel Davis that the vaunted surge of troops in Afghanistan, despite being billed as guaranteed to work as well as the Iraq surge, has been a complete failure.

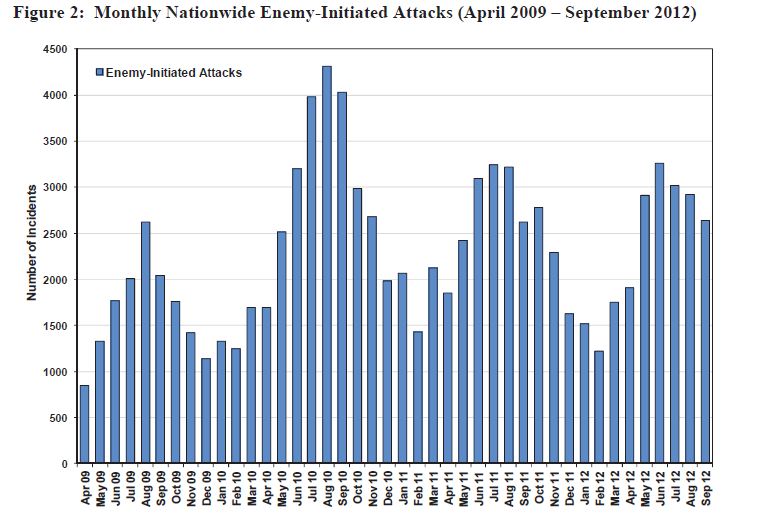

Here are the latest results on enemy initiated attacks, on a monthly basis:

Note that in order to not remind us of how violence escalated in Afghanistan while our troops were present, this figure cuts off the early years of the war. A similar chart, with the early years included (but showing events on a daily basis rather than monthly, so the scale is different) can be seen in this post from early last year. However, by cutting off the early years, the Defense Department allows us to concentrate on the surge and its abject failure. Obama’s surge began with his order in December, 2009, so this graph gives us 2009 as the base on which to compare results for the surge. Despite a small decrease in violence from the peak in 2010, both 2011 and 2012 are worse than 2009, the last pre-surge year.

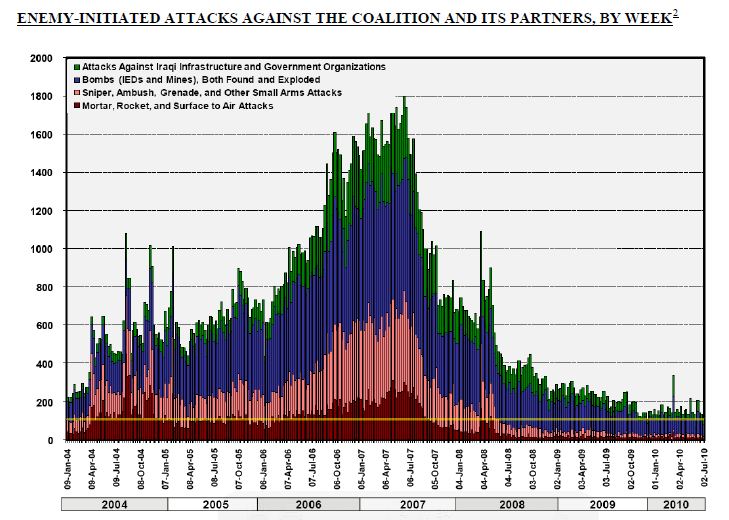

But how could the surge fail? Recall the “awesome” results from the Iraq surge (pdf). That eighteen month surge ended in July of 2008:

Daniel Davis explains how the reduction in violence in Iraq was unrelated to the surge or Petraeus’ vaunted COIN strategy. From my February post on the Davis report:

Once we realize the fact that the surge in Afghanistan has not worked, the natural question arises of why it didn’t since the Iraq surge is so widely credited with turning around the violence trend there. After all, both surges have been sold as the model for the new COIN centered around the idea of protecting the population.

The answer here is that we were sold lies about the underlying forces behind the decrease in violence in Iraq. In short, violence decreased for reasons mostly unrelated to the surge and the new COIN approach. From page 57:

“As is well known, the turning point in 2007 Iraq came when the heart of the Sunni insurgency turned against al-Qaeda and joined with US Forces against them, dramatically reducing the violence in Iraq almost overnight. The overriding reason the Sunni insurgency turned towards the United States was because after almost two years of internal conflict between what ought to have been natural allies – al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) and the greater Sunni insurgency – a tipping point was reached whereby the Iraqi Sunnis finally and decisively turned against AQI. Had this unnatural split not occurred, by all accounts I have been given on both the Iraqi side and the US military side, “we would still be fighting in Iraq today,” in the words of two officers I know who fought there.”

There simply has been no turning against insurgents in Afghanistan in the same way there was in Iraq. The COIN strategy has been the same in both places, so it is impossible to escape the conclusion that the military’s current version of COIN alone is insufficient to end violence in Afghanistan.

The Petreaus-Allen-Broadwell-Kelley scandal very conveniently will prevent this evidence of failure receiving the attention it deserves. Should Congress decide to take a realistic look at Afghanistan, it’s hard to see how they can conclude anything other than that our presence has accomplished nothing but death and destruction. Getting out now rather than two years from now is the only responsible decision.

Ahem.

“The COIN strategy has been the same in both places, so it is impossible to escape the conclusion that the military’s current version of COIN alone is insufficient to end violence in Afghanistan.”

In reality, the COIN strategy is and has been irrelevant in both places. It has been true throughout history that, if one people/country moves into the turf another people/country and tries to stay there beyond their welcome (in time or scope), there will be some level of insurgency. From post-war Germans jokingly the chimneysweep on the tram to brush his sooty clothes against my German-speaking Dad in his class A uniform (my dad surprised them, in perfect colloquial German, reminding them it would not be a good idea) to some Afghan or Iraqi setting an IED, if you are unwelcome there will be resistance and aggression. And the surest way to be unwelcome is to act the way the US did – trashing the place, acting for all the world like you intend to take it and keep it, and torturing the locals who disagree.

So, all the fine academic refinements of COIN strategy are really just career builders and brownnosing to the political PTB. The military is notoriously hostile and resistant to original thought (when that thought is not directed at creating new tools for killing their fellow man), and a “new” COIN strategy (in reality, the failures of Vietnam in a new shiny PR’d-up wrapper) would have had no chance if it were not seen as a way to keep the wars, the promotions, the medals, and the budgets going.

In other words, so much bullshit.

@scribe: Very good description, thanks.

As much as I’d like to agree, what I know about interrupted time-series analysis won’t let me. There is often a lag between the application (and/or removal) of a treatment and the change in the dependent variable. Thus, they can argue that the delayed turn-around in Iraq after the beginning of the surge is still evidence that it worked, and that the delayed leveling off after the surge ended also shows that it worked (although that’s more likely a floor effect than anything else).

Now, you can try to counter by saying that there should not be any delay in the effects of more troops and more power to you. But it won’t be a slam-dunk either way. They are spinning the data in the most positive way; you are spinning it in an opposite way. Without a lot of additional information, the truth is in the eye of the beholder.

With all that said, I see no way to spin the Afghan data in a positive way. That’s an utter failure.

@JTMinIA: Perhaps, but there is more than just spinning two sets of results here. One has the presence of the Sunni Awakening–which does fit perfectly the timing of the decline of violence– and the other has no such event and does not feature the decline, even with an extra year and a half to two years for response if the two surge starts are aligned.

Is it possible that “our” leaders are just updating and reposting the USSR’s press releases for their Afghan war. It’s almost like they don’t even care enough to polish the turd.

@Jim White: Again, I want to agree and the Sunni Awakening explanation has a lot of merit and, IMO, is more likely correct. The problem is: you can’t know for sure.

In an ideal world, people would know about the limits of this sort of analysis and you would not now have to argue against the “evidence” that the Iraq surge worked because it would be known that we have no definitive evidence. I’m just saying: please don’t make the opposite mistake. Everyone needs to face the fact that there are myriad confounds, so these data do not tell us anything clearly.

Aside: human love to infer causation from what are merely coinky-dinks. It’s what leads to all those little superstitions in sports and elsewhere. What I find weird is how our drive to be able explain stuff – especially important stuff – causes us to make fun of the athlete who picks his nose in a certain way before he bats because he once hit a home run with a booger on his finger, but then we hail Patreaus as a genius based on pretty much the same evidence that our nose-picking batter used.

Yeah, I can be a real snob (or should I write “snot”?) when it comes to faulty reasoning.