I suppose I should have reminded readers, somewhere in my close tracking of Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly’s attempt to craft a nifty solution to a difficult Fourth Amendment question, that she authored a 2004 FISA opinion from which a decade of bulk collection on Americans arose.

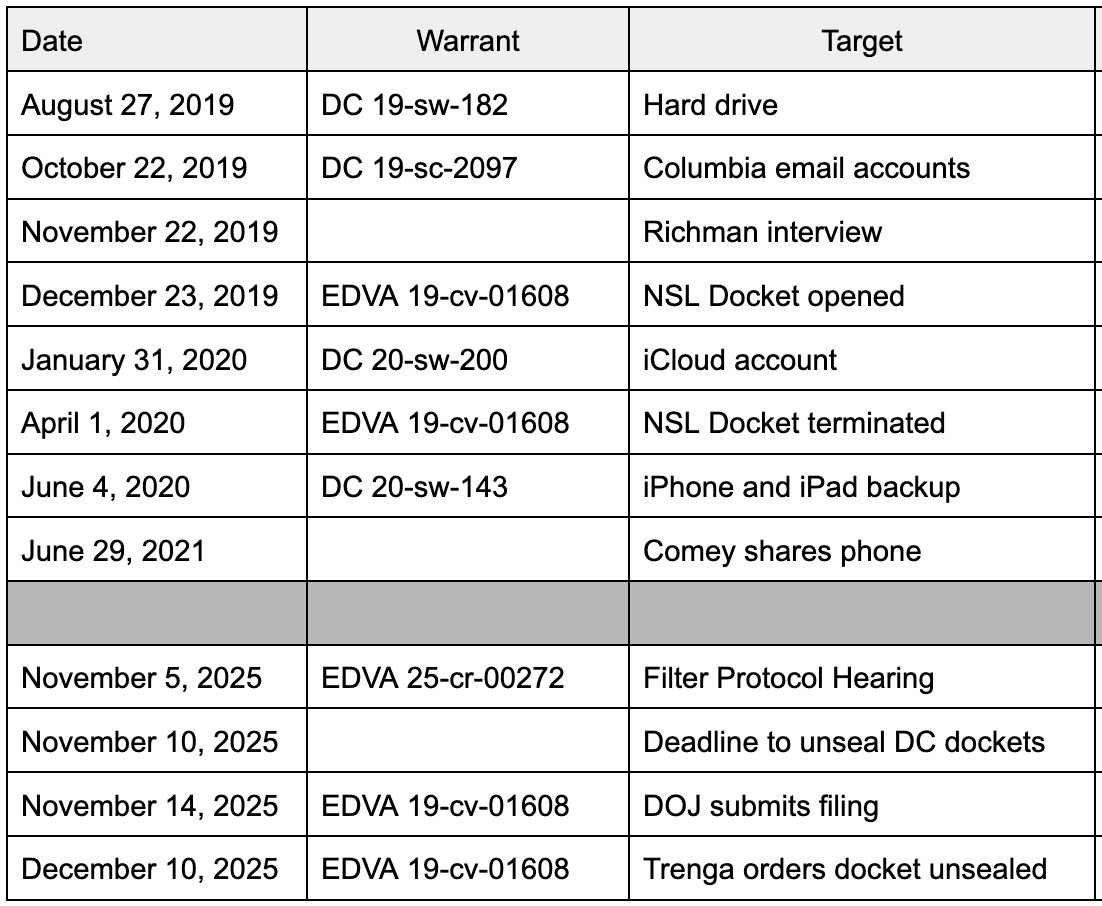

I delayed doing so, in part, because Tulsi Gabbard has deprecated the link to the official version and so I need to go find a copy. But this post describes the substance of the opinion. This post describes how subsequent phone dragnet opinions relied on it. And this timeline explains how, after Kollar-Kotelly was just the second FISA Judge read into the unconstitutional Stellar Wind program, and after she raised concerns about it, a guy named Jim Comey refused to reauthorize it in its then current form, which led to a famous standoff in a hospital, much drama, but only limited (and still largely undisclosed!) changes in the program, before Kollar-Kotelly wrote an opinion authorizing bulk collection that would be the cornerstone for 11 more years of bulk collection.

Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly has a history with difficult Fourth Amendment decisions.

And she has a history with Jim Comey.

When we last reviewed this difficult Fourth Amendment question, Kollar-Kotelly had simply waved her hands over the original sins of unscoped seizures and overseized data targeting Dan Richman — which she deemed plausible Fourth Amendment violations but not something she had to deal with, she said, because she had found the later search of that likely unscoped data was itself a violation of the Fourth Amendment and so could apply a bunch of DC precedents that all addressed property that was, in the initial seizure, lawfully collected to data she agreed was plausibly also unlawfully collected. Then she ordered the government to send that unlawfully searched data to EDVA, where different precedents would apply, and where the government could get a warrant to access what they wanted.

In a motion to modify and clarify that was also, in a footnote, a motion for reconsideration, the government deftly asked to change the rules such that they would be able to keep the fruits of several iterations of unlawful searches, and Dan Richman would be gagged from revealing that’s what happened.

So here’s what Kollar-Kotelly — she of the history of difficult Fourth Amendment decisions and she with the two decade history with Jim Comey — has done since.

First, she issued an order bitching about the government’s last minute request and complaining that they didn’t raise these issues on the first go-around, but giving the government permission to keep anything derivative of those three iterations of unlawful seizures.

The Government’s [22] Motion, which was filed approximately one hour before the deadline for the filing of a certification of compliance set forth in this Court’s [20] Order, raises a variety of issues related to the handling of classified information and information that may be subject to the Government’s own privileges, including the attorney-client privilege and the deliberative process privilege. The Government could have-and should have-raised many of these issues earlier in its initial Response to Petitioner Richman’s [1] Motion for Return of Property, but it did not do so. The Court will clarify its [20] Order at greater length by separate order and, if appropriate, will request further briefing from the parties. For now, the Court notes three important clarifications:

[snip]

Further, this Court’s Order directed the return of Petitioner Richman’s own materials (and any copies of those materials), not any derivative files that the Government may have created. See Order, Dkt. No. 20, at 1 (directing the return of the original materials, copies of those materials, and any materials “directly obtained or extracted” from them); see also id. at 41 (explaining that the Court would not bar the Government from “using or relying on” the relevant materials in a separate investigation or proceeding). Accordingly, compliance with the Court’s Order will not intrude upon any of the Government’s privileges.

This order, by itself, would amount to permitting the government to use stuff tainted by a breach of attorney-client privilege (Jim Comey’s attorney-client privilege), something she has not dealt with at all.

Then yesterday, Kollar-Kotelly issued an order noting (in a footnote) the government request for reconsideration they buried in a footnote, but blowing it off …

1 In a footnote, the Government requests reconsideration of this Court’s merits ruling that the Government’s retention of the materials at issue violates Petitioner Richman’s Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable seizures. See Gov’t’s Mot., Dkt. No. 22, at 7 n.5. However, the primary focus of the Government’s [22) Emergency Motion is the proper scope of the remedy to be awarded. Accordingly, the Court focuses here on issues that are directly relevant to the issue of remedy.

… But also requiring (among other things) the parties to explain three things, with the following deadlines:

- By 9:00 a.m. ET on Wednesday, December 17, 2025, the government should share its great ideas on how to keep all this data secure at EDVA.

- By 10:00 a.m. ET on Wednesday, December 17, 2025, the government should explain what it has from the original searches.

- By 2:00 p.m. ET on Wednesday, December 16, 2025, Richman should explain what he wants back, some of which may be influenced by the 10AM briefing.

The order pertaining to that 10AM explanation betrays how inadequate the original baby-splitting solution was, not least because Kollar-Kotelly doesn’t unpack that the stuff the government originally seized from Richman is evidence — or at least includes it.

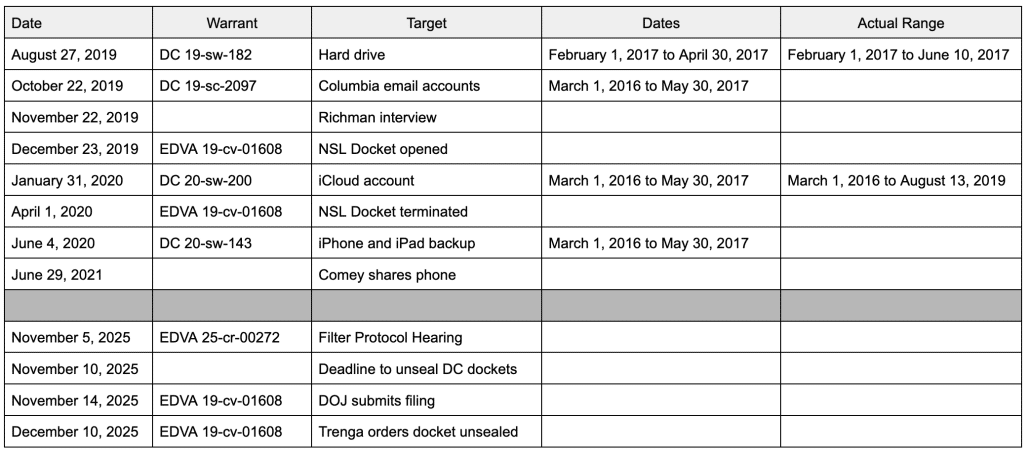

Second, the Government argues in its [22] Emergency Motion that the Court’s Order “appears to require the Government to delete or destroy evidence originally, and lawfully, obtained pursuant to search warrants issued by the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia in 2019 and 2020.” Gov’t’s Mot., Dkt. No. 22, at 5. To be clear, the Court has not ordered the Government to delete or destroy any evidence; instead, it has ordered the Government to return certain materials to Petitioner Richman, while depositing others with a third-party custodian for safekeeping. However, to ensure that the remedy awarded in this case is appropriately tailored to the facts, the Court would benefit from more factual details regarding the Government’s execution of the search warrants issued in this District in 2019 and 2020. Id. Accordingly, it is ORDERED that, no later than 10:00 a.m. ET on Wednesday, December 17, 2025, the Government shall file with the Court a brief response to the following questions:

(1) Does the Government have in its possession a complete copy of any of the following:

(i) the “forensic image” of Petitioner Richman’s personal computer hard drive that the Government was authorized to search under the warrant issued in this District on August 27, 2019;

(ii) the information disclosed by Columbia University to the Government pursuant to the warrant issued in this District on October 22, 2019;

(iii) the information disclosed by Apple to the Government pursuant to the warrant issued in this District on January 30, 2020; or

(iv) the “contents of a hard drive … containing backup files of one Apple iPad 4 and one Apple iPhone 5S” that the Government was authorized to search under the warrant issued in this District on June 4, 2020?

(2) Under each of the four search warrants at issue, the Government was authorized to seize only responsive material, which constituted a subset of the information it was permitted to search. Did the Government create a separate file, disk, hard drive, or any other segregated collection of responsive material for any of the following:

(i) the material seized from Petitioner Richman’s personal hard drive pursuant to the warrant issued in this District on August 27, 2019;

(ii) the material seized from Petitioner Richman’s Columbia University email accounts pursuant to the warrant issued in this District on October 22, 2019;

(iii) the material seized from Petitioner Richman’s iCloud account pursuant to the warrant issued in this District on January 30, 2020; or

(iv) the material seized from the backup files of Richman’s Apple iPad 4 and Apple iPhone 5S pursuant to the warrant issued in this District on June 4, 2020? [my emphasis]

As Kollar-Kotelly alludes to elsewhere, these questions should have been answered before she made her original decision. But she doesn’t acknowledge that she would have needed this information, in part, to understand whether the first two seizures violated the Fourth Amendment, which — if they do — would mean her application of multiple precedents that all assume the initial seizure was lawful would be totally inapt.

But there are two reasons why even these belated questions are inadequate to her purpose.

First, as Kollar-Kotelly noted in her own opinion, which she cited via William Fitzpatrick’s opinion which in turn cited this FBI declaration, when the FBI searched all this data in September, they searched a full extraction of Richman’s phone and iPad.

For this search, an FBI agent was instructed to review “a Blu-ray disc that contained a full Cellebrite extraction and Reader reports” for two of Petitioner Richman’s devices to identify “conversations between [Petitioner Richman] and [Mr. Comey].”

As the full quote from the FBI declaration explained, when Francis Nero did that search, he received a Blu-ray sealed with red evidence tape.

On or about September 12, 2025, while assigned to the Director’s Advisory Team, I was requested by Special Agent Spenser Warren to review a Blu-ray disc that contained a full Cellebrite extraction and Reader reports of an iPhone and iPad backups. I was requested to review the Cellebrite extraction for conversations between RICHMAN and JAMES COMEY. SA Warren handled this agent a manilla envelope sealed with red evidence tape that contained the Blu-ray disc with the Cellebrite extraction.

We know this full extraction contained attorney-client communications. Kollar-Kotelly doesn’t ask, in her second question above, how privileged communications were treated back in 2019 and 2020. She needed to ask whether the FBI only scoped the data not covered by Richman’s privilege declarations (which is what happened, if they scoped it at all) or whether they gave him scoped materials on which to make privilege declarations. Whichever it is, though, there needs to be a question 3, because the government never had the right to search privileged materials (except, arguably, on the original image itself, because such searches were not yet explicitly prohibited).

More importantly, if Spenser Warren handed Nero the full extraction, then it doesn’t matter what happened in step 2 of Kollar-Kotelly’s question above, because the government simply searched, without a warrant, unscoped data that should have been destroyed. That red evidence tape may well be what the government did to ensure that the FBI didn’t snoop on unscoped data. If so, the smoking gun in this chain of unlawful seizures was the decision, by someone on the Director’s Advisory Team, to search unscoped data without a warrant. That’s not covered by Kollar-Kotelly’s questions at all.

The other reason Kollar-Kotelly’s questions are inadequate is because of this disclosure (which didn’t make Fitzpatrick’s opinion and so may not be before her).

5 The Order also required the government to provide, in writing, by the same deadline: “Confirmation of whether the Government has divided the materials searched pursuant to the four 2019 and 2020 warrants at issue into materials that are responsive and non-responsive to those warrants, and, if so, a detailed explanation of the methodology used to make that determination; A detailed explanation of whether, and for what period of time, the Government has preserved any materials identified as non-responsive to the four search warrants; A description identifying which materials have been identified as responsive, if any; and A description identifying which materials have previously been designated as privileged.” ECF No. 161 at 1-2.

Despite certifying on November 6 that it had complied with the Court’s Order, ECF No. 163, the government did not provide this information until the evening of November 9, 2025, in response to a defense inquiry. The government told the defense that it “does not know” whether there are responsive sets for the first, third, and fourth warrants, or whether it has produced those to the defense, and said that in that regard, “we are still pulling prior emails” and the “agent reviewed the filtered material through relativity but there appears to be a loss of data that we are currently trying to restore.” [my emphasis]

On November 9, in response to the same questions Kollar-Kotelly asked in her order but posed by Fitzpatrick, the government told Comey — but not in writing! — that they had no fucking clue what happened with the first, third, and fourth warrants, because something happened with Relativity, the software on which these distinctions would have been preserved. So they had to pull prior emails to figure out what the fuck they were doing searches on.

The government may still have no fucking clue what they’re dealing with, because they asked for a 48-hour extension on both their own deadlines.

Richman agreed to that delay but only if he also got an extension.

Counsel for Petitioner has informed the Government that he takes no position on this request, but respectfully requests that the Court provide Petitioner an equivalent extension of time to file his brief, see ECF No. 27 at 3, should the Court grant the Government’s motion.

Late yesterday, Kollar-Kotelly issued a docket order granting the government its two-day extension on the easier question — how to keep this data secure at EDVA — but just a two hour extension to the harder deadline — what the fuck happened with this data. She did not, however, grant Richman an extension at all, so his response must now be filed two hours after the government’s response.

The Court is in receipt of the Government’s 28 Motion for Additional Time to Respond to this Court’s 27 Order for supplemental submissions, which the Government filed at 6:28 p.m. ET this evening. The Government’s 28 Motion is GRANTED IN PART and DENIED IN PART. The Government’s Motion is GRANTED as to the 9:00 a.m. deadline for the submission of “best practices on safekeeping evidence,” which is CONTINUED to 9:00 a.m. ET on Friday, December 19, 2025. The Motion is GRANTED IN PART and DENIED IN PART as to the Government’s deadline to respond to the factual questions presented in this Court’s 27 Order. The Government shall file brief responses to these questions no later than 12:00 p.m. ET on Wednesday, December 17, 2025. The Motion is otherwise DENIED. Petitioner Richman’s response deadline is unchanged.

Again, Kollar-Kotelly needed answers to these questions before she crafted the baby-splitting solution. Because if the original data was overseized and then not preserved in its scoped form (or if someone fiddled with Relativity in the interim to muddle what data was properly seized in the first search), then her application of DC precedent was inappropriate. At least some of this data was — as far as we know (though there may be other warrants) — always unlawfully seized.

That 2004 opinion Kollar-Kotelly wrote was an attempt to solve an enormous problem caused by unlawful government spying, but it served as the cornerstone for 11 more years of unlawful government spying. This particularly baby-splitting solution may lack the gravity of that earlier opinion, but in its currently muddled form, has the potential of causing another decade of problems.

Update: DOJ’s response is here. They actually admit to the problem with Relativity (though don’t name Relativity and try to obscure the timing of DOJ dropping it, which almost certainly has to post-date the January 6 investigation).

These responses are provided with the qualification that the search warrants were obtained five and six years ago.

[snip]

Search warrants directed at these materials were issued by the United States District Court for the District of Columbia. These warrants included language for following a filter process for attorney-client privileged information. As to the iCloud account and backup files for the iPad 4 and iPhone 5S, these materials were combined and provided to Richman and his counsel for filtering. The filtered version was then provided back to the government for review. Correspondence reviewed by the present investigative team indicates that the primary case agent then committed to reviewing the filtered version through an e-discovery program. Between 2020 and 2025, the Department of Justice stopped using this e-discovery program and a loss of data occurred. The government has attempted to restore this data but has not been successful.

The government has contacted the primary case agent. The primary case agent stated that he always followed and complied with the terms of a search warrant, and that his behavior in this case would have been no different. However, due to the passage of time [redacted], the primary case agent could not specifically describe the process followed in 2019 and 2020.

In a redaction in this passage and an earlier one (for which DOJ appears not to have filed a motion to seal), they must describe something that happened to the original lead case agent. That is, for some reason he can’t fully reconstruct what he did five years ago.

And they have yet to reconstruct what was lost in dropping Relativity.

In short, they’re basically saying these warrant returns are so old, neither the person who managed them nor the software paid to preserve them are available to do so any longer.

Their solution to that, DOJ says, is for them to have a filter AUSA and a filter Agent review it all to find out if there is a segregated version within the larger set.

Finally, as to the materials described in this section, the government respectfully requests that the Court allow a filter FBI agent and a filter AUSA to review only the previously filtered versions, which, according to FBI records, are contained on the relevant storage devices. The purpose of this limited review would be to determine whether any sort of segregated version of responsive material exists on the storage devices.

This should change Kollar-Kotelly’s entire approach. DOJ confesses they have no fucking clue whether the data they have is legal or not.

But it likely will not.

Update: Richman’s response is here. It goes big, demanding that all materials be taken away from the government.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)