Aikins in Rolling Stone: Zakaria Kandahari Was in Facebook Contact With Special Forces After Escaping Arrest

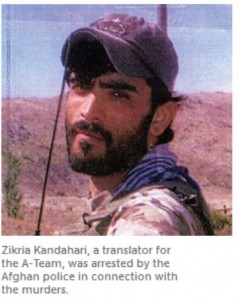

By now, you undoubtedly have heard about Matthieu Aikins’ blockbuster story published yesterday by Rolling Stone, in which he provides a full description of war crimes carried out by Special Operations forces in the Nerkh District of Maidan Wardan province, Afghanistan. [If not, go read it in full, now!] I began following this story closely back in February when Hamid Karzai demanded the removal of all Special Operations forces from Maidan Wardak because of the crimes committed by this group. As more details of the crimes slowly emerged after that time, it became more and more clear that although several members of the US Special Operations A-Team participated in the crimes, a translator working for them, going by the name of Zakaria Kandahari, was central to the worst of the events. It eventually emerged that Karzai had demanded in January that the US hand Kandahari over for questioning, but the US eventually claimed that Kandahari had escaped. I had viewed that claim with extreme skepticism. Details provided by Aikins at the very end of his article provide justification for that skepticism, as it turns out that while Kandahari was “missing”, he appears to have used Facebook to stay in contact with the Special Operations team of which he had been a part.

Back in May, the New York Times carried an article detailing some of the charges against Kandahari and providing a description of his disappearance. Note especially the military’s multiple claims that they had nothing to do with the disappearance and did not know where he was:

Afghan officials investigated the events in the Nerkh district, and when they concluded that the accusations of misconduct by the team were true, the head of the Afghan military, Gen. Sher Mohammad Karimi, personally asked the American commander at the time, Gen. John R. Allen, to hand Mr. Kandahari over to the Afghan authorities.

According to a senior Afghan official, General Allen personally promised General Karimi that the American military would do so within 24 hours, but the promise was not kept, nor was a second promise a day later to hand him over the following morning. “The next morning they said he had escaped from them and they did not know where he was,” the official said.

The American official said the military was not trying to shield Mr. Kandahari. “The S.F. guys tried to pick him up, but he got wind of it and went on the lam, and we lost contact with him,” the official said. “We would have no reason to try to harbor this individual.”

And a spokesman for the American military, David E. Nevers, said General Allen “never had a conversation with General Karimi about this issue.”

That “we lost contact with him” is just one of the many lies put out by the military about this entire series of events. Look at what Aikins uncovered, just by finding Facebook traffic from the A-Team involved (but note that this moves Kandahari’s disappearance back to December from the previous accounts that put it in January):

“The SF guys tried to pick him up, but he got wind of it and went on the lam, and we lost contact with him,” an American official said of Kandahari in The New York Times in May. And yet after Kandahari left COP Nerkh, and as the A-Team was pressured to account for the missing men, he kept chatting with Woods and other members of the team over Facebook. On December 20th, Woods wrote on the page of his other interpreter, Hanifi, whose nickname was Danny, “when you coming back?” to which Kandahari wrote back, “he has no answer for that now Woody.” Woods replied, teasing Kandahari about his fugitive status, “Shit, they ain’t looking for Danny.” “Hahahah,” Kandahari wrote.

On April 29th, a month after the A-Team had been forced out of Nerkh by the Afghan government, and several weeks after the first bodies had been unearthed near the base, Woods posted a thank-you note on his Facebook page, naming several interpreters, including Kandahari and Hanifi. “Words can’t describe how fucking proud I am of every single one of you guys!” Woods continued, “We fucked up the bad guys so bad nonstop for 7+ months that they did everything they could to get us out of Wardak Province.” He ends with a reference to the motto of the Desert Eagles: “PRESSURE, PERSUE, AND PUNISH!!!” The same day Kandahari commented: “same back to you and all 3124 Woody. and i did what i had to do for my friends and my old team.” Both Woods and another A-Team member liked Kandahari’s comment.

The crimes carried out by this team were a major part of why several months ago I began referring regularly to these A-Teams as death squads. Aikins’ research shows that they have indeed earned that name. But note that one aspect of how these teams have been built and used in Iraq and Afghanistan is their reliance on massive surveillance. Here, for example, is Marc Ambinder in an article shortly after bin Laden’s death:

When Gen. Stanley McChrystal became JSOC’s commanding general in 2004, he and his intelligence chief, Maj. Gen. Michael Flynn, set about transforming the way the subordinate units analyze and act on intelligence. Insurgents in Iraq were exploiting the slow decision loop that coalition commanders used, and enhanced interrogation techniques were frowned upon after the Abu Ghraib scandal. But the hunger for actionable tactical intelligence on insurgents was palpable.

The way JSOC solved this problem remains a carefully guarded secret, but people familiar with the unit suggest that McChrystal and Flynn introduced hardened commandos to basic criminal forensic techniques and then used highly advanced and still-classified technology to transform bits of information into actionable intelligence. One way they did this was to create forward-deployed fusion cells, where JSOC units were paired with intelligence analysts from the NSA and the NGA. Such analysis helped the CIA to establish, with a high degree of probability, that Osama bin Laden and his family were hiding in that particular compound.

These technicians could “exploit and analyze” data obtained from the battlefield instantly, using their access to the government’s various biometric, facial-recognition, and voice-print databases. These cells also used highly advanced surveillance technology and computer-based pattern analysis to layer predictive models of insurgent behavior onto real-time observations.

So, Woods’ conversations with Kandahari on Facebook (Michael Woods is a warrant officer and member of the A-Team in question) can’t be blown off as something higher-ups in the military wouldn’t have known about. The heart of US operations in Afghanistan depends very strongly on “advanced surveillance technology” with the NSA involved. Once Kandahari was officially being sought, his communications should have been receiving special attention. And yet, he was able to have routine Facebook communication with his team and nothing came of it. Remember that it was the Afghans, and not the US, who eventually arrested him. It is impossible to come to any conclusion other than that the military was allowing Kandahari to remain “missing” and could have found him very easily had they wanted.

But here is the most infuriating aspect of all regarding what we have learned of these horrific war crimes: as the drawdown of US forces continues in Afghanistan, these types of Special Operations teams will be playing an even bigger role:

Even as the number of American troops will be cut in half from 68,000 by next February under President Obama’s withdrawal orders, the number of Special Operations forces will remain the same through the Afghan presidential election, which is scheduled for next spring, but could be delayed until closer to December 2014.

While the bulk of the American and allied conventional forces remaining in Afghanistan will make the transition to a support role — and will be increasingly based at large military headquarters — the 10,000 American Special Operations troops will continue to be deployed alongside Afghan units. (Including NATO and coalition troops, the total Special Operations deployment here numbers 13,700.)

“That partnering is rock solid, and we hope over time to come up off the tactical level,” General Thomas said. But he noted that Afghan and NATO leaders all understand the critical importance of assuring that next year’s elections are credible and secure. “So we’re probably going to stay a while longer at the tactical level than we were considering a year ago,” he added.

Whether US troops remain in Afghanistan after 2014 is dependent on achieving criminal immunity for those troops. Why would Afghanistan ever agree to immunity for the very types of forces whose behavior has been confirmed to be criminal?