John Galt Outsources Death to Bangladesh to Save Pennies on Fifty Dollar T-shirt

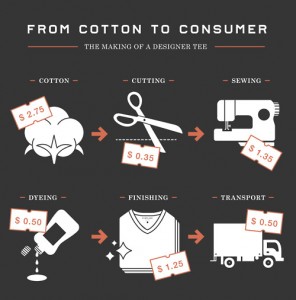

Graphic from retailer Everlane summarizing production costs for t-shirts that retail for fifty dollars.

In a tale of unimaginable sorrow that is made all the worse by the unconscionable greed that brought it about, at least 194 are now known to be dead in the collapse of a building in Bangladesh. But this was not just any building that collapsed, it was a building that housed multiple garment manufacturers. And in a pattern that has been repeated many times before, we see death brought about by the craven actions of the managers of the production companies while US retailers profess grief and claim no direct connection to the particular factories affected. Over time, once attention dies down a bit, those connections will become clear due to what appears to be a system designed to distance the retailers from the sweat shops via multiple subcontracting arrangements.

From today’s New York Times:

Search crews on Thursday clawed through the wreckage of a collapsed building that housed several factories making clothing for European and American consumers, with the death toll rising to at least 194 with many others still unaccounted for.

/snip/

The Bangladeshi news media reported that inspection teams had discovered cracks in the structure of Rana Plaza on Tuesday. Shops and a bank branch on the lower floors immediately closed. But the owners of the garment factories on the upper floors ordered employees to work on Wednesday, despite the safety risks.

Labor activists combed the wreckage on Wednesday afternoon and discovered labels and production records suggesting that the factories were producing garments for major European and American brands. Labels were discovered for the Spanish brand Mango, and for the low-cost British chain Primark.

Activists said the factories also had produced clothing for Walmart, the Dutch retailer C & A, Benetton and Cato Fashions, according to customs records, factory Web sites and documents discovered in the collapsed building.

The drive to save pennies on garments is directly behind this and similar tragedies:

“The front-line responsibility is the government’s, but the real power lies with Western brands and retailers, beginning with the biggest players: Walmart, H & M, Inditex, Gap and others,” said Scott Nova, executive director of Worker Rights Consortium, a labor rights organization. “The price pressure these buyers put on factories undermines any prospect that factories will undertake the costly repairs and renovations that are necessary to make these buildings safe.”

These sorts of tragedies happen with alarming regularity. Last September, at least 258 people died in a fire in a Karachi garment factory that had escaped safety inspections.

And note that although governments are cited in these tragedies for failing to provide adequate regulation and inspections, it is the tremendous pressure applied by US retailers to reduce production costs that drives many of the decisions that put workers at risk of death.

But these retailers are chasing very tiny cost reductions in the overall retail prices of garments. The graphic above is taken from a Tumblr post by retailer Everlane (they are touting their own business model of removing wholesalers, so they do have a particular point of view in promulgating the numbers). In this version of the industry, we see $1.35 going to the workers who sew a shirt and thirty five cents to the worker who cuts the fabric. The overall direct costs in this case come to $6.70. The second half of the graphic in the Tumblr post shows that the the t-shirt is then sold to a wholesaler for $15 and the retailer then sells to a consumer for $50.

At least when it comes to designer t-shirts retailing for $50 (okay, that leaves out WalMart but from these stories it looks as though at least some high end retailers and the low price retailers share many of the same garment factories) the wages paid to garment workers are only a few percent of the overall retail price. And yet the companies apply huge pressure to the owners of the garment factories because John Galt tells them that the “job creators” at these name-brand labels deserve huge profits while governments must stay out of the way of the engines of wealth.

The concept of the fifty dollar designer t-shirt is getting some popular culture push-back. From the lyrics of “Thrift Shop”, by Macklemore and Ryan Lewis:

I hit the party and they stop in that motherfucker

They be like “Oh that Gucci, that’s hella tight”

I’m like “Yo, that’s fifty dollars for a t-shirt”

Limited edition, let’s do some simple addition

Fifty dollars for a t-shirt, that’s just some ignorant bitch shit

I call that getting swindled and pimped, shit

I call that getting tricked by business

That shirt’s hella dough

And having the same one as six other people in this club is a hella don’t

Peep game, come take a look through my telescope

Trying to get girls from a brand?

Man you hella won’t, man you hella won’t

Rejecting artificial demand created by a name brand label that exploits low wage garment workers would be wonderful first step toward improving the situation. However, this move needs to be followed by actively embracing the concept of living wages and safe working conditions if the evils of the current situation are to be addressed fully.

And, well, because it’s fucking awesome:

[youtuber youtube=’http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QK8mJJJvaes’]

From today’s NYT:

Factories making clothing? What about “factories whose employees/workers/PEOPLE were making clothing?”

The PEOPLE don’t exist.

I notice that graphic left out everything between the cotton boll and the cutting. That’s the spinning and and knitting, which surely adds to the cost (without them, NO shirt).

Don’t forget that Matt Yglesias stands firmly on the side of the “job creators.”

@Phil Perspective: Speaking of Yggles did anyone see this?

@P J Evans: Actually leaves out the part before the cotton boll too, the kleptocracy and slavery and torture part, which Craig Murray and Scott Horton and others have been trying to bring to our attention and consciences, e.g., Uzbekistan’s cotton slavery / http://www.craigmurray.org.uk/archives/2013/01/uzbek-cotton-slavery-campaign/

Has youtube (“This is a story of a dictator who got away with it…”), with transcript posted in comments. Worth reposting here I think:

@thatvisionthing:

Depends on where the cotton is from. (I know that the cotton from west Texas is mostly used in denim.) It requires water, a lot of fertilizer, and at least 180 days frost-free. (Frost after the bolls open is good, though.)

@P J Evans: PJ, I heard a story recently (podcast? radio?) about Afghanistan farmers who have quit growing cotton that we had encouraged them to grow, and returned to growing opium because cotton didn’t pay. I was thinking it must be hard to compete to the bottom with slave labor next door in Uzbekistan, and Murray’s post makes it clear that slave market is supported by the West and NATO, especially Germany.

Hi Jim,

Didn’t know if you saw this:

What Went Wrong in West, Texas — and Where Were the Regulators?Theodoric Meyer; ProPublica,4/25/13

Also, the music is awesome, as is the phrase Bush Lie Bury!

@harpie: Thanks, harpie. I hadn’t seen that one, but I am encouraged that the whole concept of how poor regulation and zoning led to the disaster is starting to see more and more attention.

Here’s more awesomeness by Macklemore on another social issue:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hlVBg7_08n0

@thatvisionthing: I read Craig Murray’s blog most days, he often goes for a spell without posting but I check every day, and think as I read how wonderful it would be to have more like him.

This is off topic but his talk at the Sam Adams Awards was excellent and worth a look. The entire talk, with many noble contributors is useful but Craig’s speech starting at the 15 minute mark is marvellous. http://www.craigmurray.org.uk/archives/2013/03/of-this-i-am-proud/

He has also made much of what he’s written freely available, see the side bar on his blog.

Give me tariffs or give me death ………….

Why are we trading with these people?

@Jim White:

Jim, I just wanted to tell you I used your “Lie Bury” phrase in a comment on a Greenwald column, here.

@harpie: As might be expected, I was not the only one to come up with that phrase. Over at Political Carnival, Paddy found an editorial cartoon using it:

http://thepoliticalcarnival.net/2013/04/25/cartoons-of-the-day-george-w-bush-presidential-library/

My prayers to the victims of a T shirt factory in Bangladesh! It is also our priority to check out the condition of the workplace f our suppliers. We must not only base on cheap outsource product but also the safety of workers.

mae