I was interested to read this post from Matt Yglesias, which purports to prove that “nothing will bring back manufacturing employment.” Yglesias’ logic is that overall manufacturing employment is falling, largely because of more automation, and so we should stop pushing manufacturing in this country because it doesn’t get us the nice things in life. Here’s his key graf, which I’ll return to.

If you think about what the typical American family needs more of, it’s not manufactured goods. People need cures for illness and educational opportunities for their kids. They need more time to spend on leisure activities and with their family. They need jobs they enjoy. The idea of promoting more widespread affordability of health care services by boostering the share of the population that works in factories is a bizarre Rube Goldberg mechanism compared to directly focusing on improving the health care sector’s ability to deliver useful treatment to people.

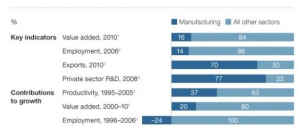

Before I get there, though, compare the graphic he uses for his post:

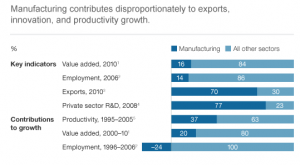

And the one in the McKinsey report he claims supports his argument:

See what he left out? The bit where his chosen source says,

Manufacturing contributes disproportionately to exports, innovation, and productivity growth.

That is, Yglesias stripped McKinsey’s title describing how important manufacturing is to a successful economy, including one that (if workers have some kind of workplace power, which is a big if) contributes to them having time to spend with their families and enjoyable jobs.

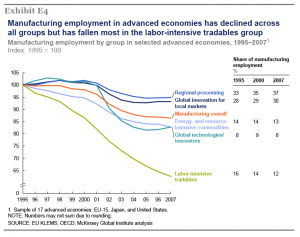

Here’s the graphic he should have used, showing that labor intensive manufacturing has nose-dived, while showing a decline–with a more recent slight up-turn–in more innovative manufacturing, and a decline then plateau in a number of other manufacturing categories.

And, as the text of the report makes clear, these labor intensive jobs haven’t just been outsourced; they’ve also been automated. That’s Yglesias’ point: this one kind of manufacturing is declining, and not just in the US.

That is, there’s a teeny part of the report that supports Yglesias’ point: these labor intensive jobs–which are different from manufacturing jobs, generally!–aren’t coming back.

But Yglesias has made those labor intensive manufacturing jobs stand-in for all of manufacturing, all while relying on a report that repeatedly insists that manufacturing is not monolithic. To be fair, I think Yglesias may actually believe manufacturing consists solely of those labor intensive jobs (he doesn’t consider, for example, that a key part of innovation in medical treatment involves medical devices and diagnostic machines that have to be–you guessed it!–manufactured, and are done so much better in close proximity to the treatment they deliver).

Underlying Yglesias’ treatment of labor intensive manufacturing as a stand-in for all manufacturing is a straw man argument he suggests–he does not voice it explicitly, but it’s the only way his formulation on the social value of manufacturing makes sense.

Manufacturing = only icky manufacturing jobs = no intrinsic benefit to society = poor policy investment

Now, as Yglesias’ source shows, manufacturing also includes a bunch of high tech jobs involving tailoring products to consumer needs. Those jobs are on the upswing, particularly in developed economies, as manufacturing focuses more on customization. They bring the kind of productivity improvements–for customers–that align with Yglesias’ description of all that is good in life.

As the McKinsey report also shows, manufacturing leads to and supports service jobs.

Manufacturing companies rely on a multitude of service providers to produce their goods. These include telecom and travel services to connect workers in global production networks, logistics providers, banks, and IT service providers. We estimate that 4.7 million US service sector jobs depend on business from manufacturers. If we count those and one million primary resources jobs related to manufacturing (e.g., iron ore mining), total manufacturing-related employment in the United States would be 17.2 million, versus 11.5 million in official data in 2010.

So while those labor intensive manufacturing jobs may not be coming back, to the extent we have manufacturing in this country, it does support a number of jobs that are not classified as manufacturing in the kinds of service sectors Yglesias more readily supports.

But finally there’s the key point that graphic Yglesias put into his own post shows: Manufacturing may make up a small portion of the actual jobs out there. But it is central to innovation and productivity.

What the country has been doing by emphasizing manufacturing is not–as Yglesias tends to suggest–subsidizing a bunch of labor intensive jobs in smoky 100-year old factories. Rather, to the very limited extent that Obama has invested in manufacturing more than his predecessors (which primarily consists of saving a domestic auto industry and investing in energy manufacturing), it has involved investing the bare minimum necessary to ensure our country participates in some but by no means all the industries that are driving key innovations.

A manufacturing policy is a jobs program as much through the secondary jobs manufacturing supports as through the manufacturing jobs themselves.

But a manufacturing policy is a competitiveness program because that’s where innovation comes from. Without that you don’t get some of the nice things Yglesias talks about–more leisure time and medical cures and more enjoyable jobs.

That’s where Yglesias logic collapses–in the “and so” I bolded above. Sure. We will never have as many labor intensive manufacturing jobs as we used to have. We will, depending on our policies, have more innovative manufacturing jobs than we have now, along with the service jobs that come with those manufacturing jobs. But if we make those policy choices, we will also renew America’s commitment to remaining at the cutting edge of innovation across multiple industries, something without which we can’t have a lot of the nice things Yglesias just assumes come of themselves. That’s what the policy debate is about, not those labor intensive jobs in 100 year old factories, no matter how much Yglesias would like to caricature it as such.

I agree with Yglesias on this: Americans don’t need more closets full of cheap manufactured goods.

But that is different from saying that Americans don’t want more sophisticated medical technology or smart phones that integrate cutting edge materials and electronics or safer, more efficient cars–and the attendant new technologies and service jobs that come with these things. And that is also far different from saying that Americans don’t want to be the most advanced country in the world anymore because their government and society just aren’t willing to invest in competitiveness the way the Chinese or Koreans or Germans are.

The logic of Yglesias’ post is that a country doing what it needs to to remain innovative and competitive is some kind of Rube Goldberg deal. That logic only sustains if you have a really outdated understanding of what manufacturing is. I don’t think that’s what Yglesias really believes, which is why he might want to read the McKinsey report he cited in some more detail.