There’s been a good deal of reporting on this report the NYCLU released last week, but the report itself must be read to fully understand the gravity of the stop-and-frisk abuse in NYC.

There’s been a good deal of reporting on this report the NYCLU released last week, but the report itself must be read to fully understand the gravity of the stop-and-frisk abuse in NYC.

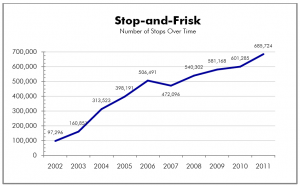

Consider this chart, for example, showing that Mike Bloomberg has had even more success inflating stop-and-frisk numbers than he ever had inflating the stock market.

Then there’s the stat that shows more young black men were stopped last year (168,126 stops of young black men) than reside in the city over all (158,406 total)–statistically, at least, every single young black man has been stopped.

Finally, though, there’s the list of reasons cops gave for having stopped someone in the first place–with “furtive movements” accounting for over half the stops, and “clothes commonly used in a crime” (does this mean hoodies?) cited in 31,555. What’s worse, cops only suspect a violent crime 10% of the time.

The cops frisked the person they stopped over half the time–purportedly because they suspected a weapon that might threaten the officer. Yet they found the weapon that justified the search less than 2% of the time–and weapons were more often found on white men who were stopped than blacks or LatinosIn December, Nicholas Peart wrote a devastating op-ed on what it has been like for him to mature under Bloomberg’s stop-and-frisk explosion, describing the four times he has been stopped and frisked.

Last May, I was outside my apartment building on my way to the store when two police officers jumped out of an unmarked car and told me to stop and put my hands up against the wall. I complied. Without my permission, they removed my cellphone from my hand, and one of the officers reached into my pockets, and removed my wallet and keys. He looked through my wallet, then handcuffed me. The officers wanted to know if I had just come out of a particular building. No, I told them, I lived next door.

One of the officers asked which of the keys they had removed from my pocket opened my apartment door. Then he entered my building and tried to get into my apartment with my key. My 18-year-old sister was inside with two of our younger siblings; later she told me she had no idea why the police were trying to get into our apartment and was terrified. She tried to call me, but because they had confiscated my phone, I couldn’t answer.

Meanwhile, a white officer put me in the back of the police car. I was still handcuffed. The officer asked if I had any marijuana, and I said no. He removed and searched my shoes and patted down my socks. I asked why they were searching me, and he told me someone in my building complained that a person they believed fit my description had been ringing their bell. After the other officer returned from inside my apartment building, they opened the door to the police car, told me to get out, removed the handcuffs and simply drove off. I was deeply shaken.

For young people in my neighborhood, getting stopped and frisked is a rite of passage. We expect the police to jump us at any moment. We know the rules: don’t run and don’t try to explain, because speaking up for yourself might get you arrested or worse. And we all feel the same way — degraded, harassed, violated and criminalized because we’re black or Latino.

He ends this passage by asking, “Have I been stopped more than the average young black person?” And the ACLU report makes it clear that his experience is absolutely statistically normal for a young black man.

Which presumably means the result he describes–the fear, the degradation, the criminalization–are fairly typical as well.

This systematic humiliation of one segment of our society must not be tolerated.