Will SCOTUS Invent a “Database-and-Mining” Exception to the Fourth Amendment?

As I noted yesterday, the Administration appealed the 2nd Circuit Decision granting review of the FISA Amendments Act to the Supreme Court last week. I wanted to talk about their argument in more detail here.

As I noted yesterday, the Administration appealed the 2nd Circuit Decision granting review of the FISA Amendments Act to the Supreme Court last week. I wanted to talk about their argument in more detail here.

Over at Lawfare, Steve Vladeck noted that this case would likely decide whether and what the “foreign intelligence surveillance” exception to the Fourth Amendment, akin to “special needs” exceptions like border searches and drug testing.

Third, if the Court affirms (or denies certiorari), this case could very well finally settle the question whether the Fourth Amendment’s Warrant Clause includes a “foreign intelligence surveillance exception,” as the FISA Court of Review held in the In re Directives decision in 2008. That’s because on the merits, 50 U.S.C. § 1881a(b)(5) mandates that the authorized surveillance “shall be conducted in a manner consistent with the fourth amendment to the Constitution of the United States.” Thus, although it is hard to see how surveillance under § 1881a could violate the Fourth Amendment, explication of the (as yet unclear) Fourth Amendment principles that govern in such cases would necessarily circumscribe the government’s authority under this provision going forward (especially if In re Directives is not followed…).

I would go further and say that this case will determine whether there is what I’ll call a database-and-mining exception allowing the government to collect domestic data to which no reasonable suspicion attaches, store it, data mine it, and based on the results of that data mining use the data itself to establish cause for further surveillance. Thus, it will have an impact not just for this warrantless wiretapping application, but also for things like Secret PATRIOT, in which the government is collecting US person geolocation data in an effort to be able to pinpoint the locations of alleged terrorists, not to mention the more general databases collecting things like who buys hydrogen peroxide.

I make a distinction between foreign intelligence surveillance and “database-and-mining” exceptions because the government is, in fact, conducting domestic surveillance under these programs and using it to collect intelligence on US persons (indeed, when asked about Secret PATRIOT earlier this month, James Clapper invoked “foreign or domestic” intelligence in the context of Secret PATRIOT). The government has managed to hide that fact thus far by blatantly misleading the FISA Court of Review in In re Directives and doing so (to a lesser degree) here.

In In re Directives, the government misled the court in two ways. First, according to Russ Feingold, the government didn’t reveal (and the company challenging the order didn’t have access to) information about how the targeting is used. The amendments he tried to pass–and which Mike McConnell and Michael Mukasey issued veto threats in response to–suggest some of the problems Feingold foresaw and the intelligence community refused to fix: reverse targeting, inclusion of US person data in larger data mining samples, and the retention and use of improperly collected information.

The government even more blatantly misled the FISCR with regards to what it did with US person data.

The petitioner’s concern with incidental collections is overblown. It is settled beyond peradventure that incidental collections occurring as a result of constitutionally permissible acquisitions to not render those acquisitions unlawful.9 [citations omitted] The government assures us that it does not maintain a database of incidentally collected information from non-targeted United States persons, and there is no evidence to the contrary. On these facts, incidentally collected communications of non-targeted United States persons do not violate the Fourth Amendment.

9 The petitioner has not charged that the Executive Branch is surveilling overseas persons in order intentionally to surveil persons in the United States. Because the issue is not before us, we do not pass on the legitimacy vel non of such a practice.

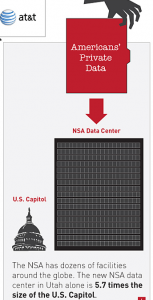

The notion that the government doesn’t have this US person data in a database is farcical at this point, as the graphic above showing the relative size of the NSA’s data center in UT–which I snipped from this larger ACLU graphic–makes clear (though the government’s unwillingness to be legally bound to segregate US person data made that clear, as well). As I suggested when this decision was released, the government must have been offering non-denial denials of having such a collection of US person data back in 2007.

Did the court ask only about a database consisting entirely of incidentally collected information? Did they ask whether the government keeps incidentally collected information in its existing databases (that is, it doesn’t have a database devoted solely to incidental data, but neither does it pull the incidental data out of its existing database)? Or, as bmaz reminds me below but that I originally omitted, is the government having one or more contractors maintain such a database? Or is the government, rather, using an expansive definition of targeting, suggesting that anyone who buys falafels from the same place that suspected terrorist does then, in turn, becomes targeted?

As I showed yesterday, the government is already doing something similar with this suit, simply ignoring the part of the suit pertaining to the completely legal retention of purely domestic communications, so long as it was ostensibly collected unintentionally.

Their larger argument, too, does something similar, using a definition of “targeting” that tautologically excludes US persons in principle but not in fact.

Section 1881a does not authorize surveillance targeting respondents or any other United States person, 50 U.S.C. 1881a(b)(1)-(3), and respondents have presented no evidence that their international communications have ever been incidentally acquired by the government in its surveillance of non-United States persons abroad.

Of course, it takes two to communicate, so for every single targeted conversation, there is a counterparty whose communications are also collected. Nevertheless, the government focuses on authorizations–the word “targeting”–to distract from these counterparties. Note too, here, how once again the government ignores 1881a(b)(4), which permits the retention of incidentally collected domestic communications.

One of the real tells, though, comes in what appears to be a throwaway intended to prove there are people who would have standing to sue under FAA.

If the government intends to use or disclose any information obtained or derived from its acquisition of a person’s communications under Section 1881A in judicial or administrative proceedings against that person, it must provide advance notice of its intent to the tribunal and the person, even if the person was not targeted for surveillance under Section 1881A. 50 U.S.C. 1881e(a); see 50 U.S.C. 1801(k), 1806(c).

The government’s reference to the possibility it would use data “even if the person was not targeted for surveillance” admits that it does collect and review the communications of those not targeted, potentially even for law enforcement purposes. But then it suggests that the only way people could be aggrieved is if their communications were used for law enforcement, not intelligence.

Yet the plaintiffs argument for injury is that they cannot do their jobs–NGOs, lawyers, reporters–even if their communications become subject to intelligence, not law enforcement, collection. Their question, of course, is whether domestic intelligence collected under the guise of foreign intelligence constitutes a violation of the Fourth Amendment, whether the government has a database-and-mining exception under the Fourth Amendment.

That may not change SCOTUS’ analysis on standing. But it does make it clear that–no matter how the government would like to distract from this point–US person data (even entirely domestic conversations) can be legally collected and analyzed under this law.

So that is what the stakes are. The government would love to have SCOTUS either deny cert or affirm the district finding that the plaintiffs don’t have standing, particularly before Jewel, which addresses the underlying issue of dragnet collection. The government would also love to use such a SCOTUS action, in secret, to rule that its use of GPS tracking in the intelligence, which it is busy distinguishing from a law enforcement context under Jones, context is legal. The government would also like any challenge to pertain to a specific order (as it would be under 1881e), so it can hide what it does with the data it collects once it goes into the database in UT.

And given what Russ Feingold said back in 2008–that an adversary process would reveal both the potential for abuse, and quite possibly the abuse, the government really really doesn’t want this case to move forward.

I would bet money you are in that data base somewhere.

“Blow job”

That one still kills me.

The Libby coverage would be my guess as to why someone at upper levels would have put you on that list.

You cute little Muckraker.

Thanks for keeping up with this, as far as I am concerned, the DHS, the Patriot Act and everything that this entails are all in violation of the Fourth amendment.

Given what Russ Feingold said back in 2008… I recall particularly the words of a Feingold-Kennedy press release of that time and place. Those two then-senators were concerned about potential misuse of NSLs.

In the years since, it appears that protected First Amendment activities have taken the hardest hit.

My dictionary says “pretext” means “a fictitious reason given to conceal a real one.” In the case at hand, pretext appears to mean lying outright.

Needless to say, if authorities can tell baldface lies to one’s employer, neighbors and acquaintances, the end effect is going to be to separate people from their jobs and traditional sources of community support. I don’t see much difference between that and blacklisting, frankly.

The database of stored communications isn’t the only thing that worries me about this. There is the real-time collection of people’s circle of contacts that I’m pretty convinced is the real driver behind this. The whole “targeting” discussion is a ruse. In addition to targeted communications of the type Marcy describes, I believe they are collected all the electronic communications between a region of interest, say, Iran and the U.S. Every phone or email address that gets a contact from the region is monitored, not for the content, but for the metadata of all their contacts. If you get a call on your cell phone from any number in the region, all the numbers you call and your cell’s location could be tracked from then on. If your interactions with the region and persons of interest get weighted high enough, your activity will be examined more closely. Note that you haven’t been targeted for electronic surveillance, at least according the definitions in use today.

Does this “database and mining exception” apply to the MOTU of Wall Street and other,assorted financial entities?

Just consider the “gold” that could be ostensibly mined…

@Bustednuckles:

ah hell, it’s even money we’re all in any number of them:

The Dick Cheney Man-Tech Safe: Libby Annex

The DOJ Rule of Law Extremist File

The DHS Mean Things Said About Lieberman & Pistole Datadump

The Foul-Mouth Fem Blogger LockBox

The CIA Blogger Brigade: Honorary Marcy Wheeler Division (staffed by former Eastern Europe Analysts whose brains don’t freeze when faced with “samizdat”& “feuilleton”)

and on.

and on.

and on…

@rosalind:

“Hi, NSA guy!”

I’ve been assuming that anyone who comments at liberal/progressive blogs got on the list under Bush/Cheney rules.

You have to wonder how easy it is for govt. to “mislead” the court when so much of the information is in the public domain. Does it seem that they are only to happy to be misled?